MRI Imaging of Spondylolisthesis

I find that the issue of spondylolisthesis has been the subject of much misinformation over the years. There are several misconceptions that I run into repeatedly in my radiology practice. I would like to review some of the basics of common spondylolistheses and hopefully dispel some of the more common, but inaccurate, beliefs.

Two Categories

The two major categories of spondylolisthesis are spondylolytic and degenerative. The spondylolytic type features actual defects of the pars interarticularis, while the degenerative type features a loss of the cartilage spacing of the facet joints as the result of facet arthrosis.

Spondylolisthesis is a relatively common finding in lumbar studies. It has been suggested in the literature that spondylolytic spondylolisthesis may occur in athletes in as many as 16.7 % of lumbar spines (1). The most commonly used grading system for spondylolisthesis divides the inferior vertebral body into quarters. Slippage of less than 25% is a grade I, 25-49% grade 2, 50-74% grade 3, 75-99% grade 4 and grade 5 is spondyloptosis, where the superior vertebra has completely slipped off the inferior body.

Misconceptions

One misconception that is commonly expressed to me is the possible “congenital” nature of a spondylolytic spondylolisthesis (SS). No evidence has been presented in the literature that this congenital condition exists. A fetus has never been identified with a pars defect. The pars is actually ossified at birth. If there were indeed a congenital etiology for SS, there would be evidence of fetuses with this abnormality. There are examples of young children with SS; however, there is no proof that any of these cases were present at birth. It is possible that an individual may have spinal malformations that could result in a spondylolisthesis; however; that is different than a congenital pars defect. These are termed “dysplastic spondylolistheses” and are rare.

Result from Trauma?

Another commonly asked question is whether a traumatic etiology is possible. It is possible for a pars defect to result from trauma; however, this again is rare. Usually the type of pars break associated with a traumatic etiology is not a clean break through the pars, but instead involves other areas of the vertebra as well. Nearly all SS are the result of stress fractures of the pars from hyperextension forces imposed upon them. This usually occurs between the ages of 10 and 15 years. Athletics may play a significant role in this etiology, particularly in sports such as gymnastics or diving.

One confounding factor in SS is the presence or absence of pain. Many individuals with SS have no back pain. Others have back pain; however, the source of the pain usually is not the spondylolisthesis itself. Pain may be a result of the spondylolisthesis if the pars is in the process of fracturing. This is termed an “active spondylolisthesis.” In these cases, physiologic imaging is beneficial in making the distinction of active versus inactive. An inactive SS is, in effect, non-union of the defect, which at this stage has no possibility of healing.

No abnormal signal intensity is seen in the pars region in the inactive stage. The majority of SS that we see are in the inactive stage. Fat-suppressed MRI imaging is particularly useful in identifying an SS in the active stage. An increased signal will be noted in the pars region on the STIR or less obviously on the T-2 weighted images at this stage. There is a possibility of healing if the SS is caught at this point. SS is most common at the L5-S1 level.

Degenerative Spondylolisthesis

The other major category of spondylolisthesis is degenerative, which is fairly common. This is the result of facet arthrosis and anterior slippage that rarely exceeds 25%. As the cartilage lining of the facets wears away, the facet surfaces approximate each other, allowing the superior vertebra to slip forward on the inferior. This type is most common at the L4-L5 level and may result in encroachment of the IVF.

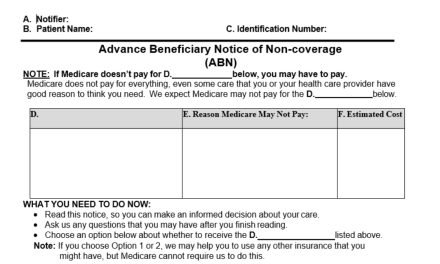

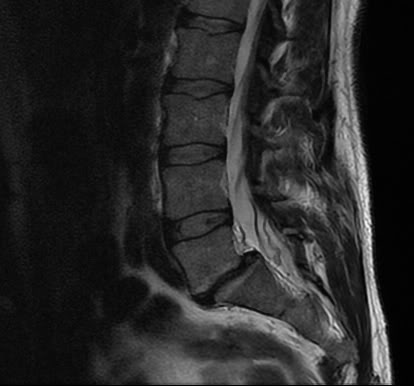

Figure 1 typifies the appearance of a grade 1 SS (anterior slippage of less than 25%) at L5-S1. Figure 2 is a T-2 sagittal cut that is oriented through the pars. There is increased signal intensity in the pars adjacent to the defect and extending into the pedicle. This is an example of an active pars defect. A stenotic IVF is seen in figure 3 at the L5-S1 level as the result of the anterior slippage. A normal IVF is outlined at L4-L5 for comparison.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.