Dysautonomia

The way the human body works and keeps us alive and functional still is beyond comprehension for even the brightest minds of the 21st century. The amount of non-conscious processing your brain and spinal cord accomplish every second is mind-blowing. While you are reading these words, your nervous system is controlling the amount of blood pumping from your heart by adjusting both the intensity of heart muscle contractions, as well as modifying the speed at which the heart pumps this blood out. Your nervous system is controlling all the blood vessels in your body, allowing for appropriate distribution of blood to flood into all of your tissues, including temporarily increasing blood into areas that you are currently using, while decreasing blood flow into areas you are not using, facilitating appropriate fuel and waste management.

Nervous System

Your nervous system is keeping you upright against gravity in a way that, hopefully, does not cause you to sway, fall, or have pain. Your nervous system is regulating your lungs in order to optimally take in oxygen and blow out carbon dioxide. Your nervous system is constantly regulating your gut’s ability to break down food enough so you can appropriately absorb the nutrients you need and expel the waste. Your nervous system controls your ability to sweat, so when you are hot you can cool down, or when you are full of toxins, you can help detoxify your body with sweating.

These are just a few of the functions your nervous system is constantly working on without your conscious control. More specifically, it is what is known as your “autonomic nervous system,” which plays a major role in these subconscious functions. The autonomic nervous system helps control every tissue and organ in your body. Most of its control is outside the realm of consciousness. The autonomic nervous system has two parts that balance each other out like a seesaw: the sympathetic system (fight or flight) and the parasympathetic system (rest and digest). When there is a problem with this balance in the autonomic nervous system, a wide range of symptoms and dysfunction may occur, and this is referred to as “dysautonomia.”

Dysautonomia

Dysautonomia is an abnormal regulation of the autonomic nervous system. Dysautonomia commonly occurs as a result of a traumatic brain injury, toxin exposure, traumatic event, bed rest, medication side effects, joint hypermobility syndromes, diabetes, neurodegenerative conditions, autoimmune conditions, and some reports have been documented post-vaccination (especially with younger females). Dysautonomia affects approximately 70 million people worldwide, and the symptoms of dysautonomia may be “invisible” to the untrained eye.

Dysautonomia is a condition that can be very debilitating in severe cases. Common symptoms of dysautonomia include lightheadedness, dizziness, increase in heart rate (especially upon change in position, such as standing up), fainting/passing out (especially with physical activity), changes in vision with positional changes, weakness, nausea, headaches, problems with balance and walking, problems with bladder, bowel, and sexual function, decreased ability to sweat, and digestive problems (for example, irritable bowel syndrome or constipation). Symptoms also can be unpredictable and change in intensity, as well as be exacerbated by emotional stressors and physical activity.

Blood Flow

For many people, dysautonomia represents abnormal function between their brains and their bodies. A common problem a person with dysautonomia may face is the proper regulation of blood within their bodies. For example, the evolution of humans to assume an upright posture and stand on two feet is typically seen as an adaptive advantage; however, with patients who have dysautonomia, fighting gravity becomes a daily challenge. When a human stands up, approximately 500 ml of blood descends from the chest into the stomach and legs. A normal response of the nervous system is to immediately constrict blood vessels in the stomach and legs, as well as slightly increase the heart rate in order to push blood up against gravity into the brain. This should all be accomplished with minimal change in blood pressure. When patients have problems with either their central nervous system, the peripheral nerves, and/or the heart/blood vessels, they will become symptomatic on changes in position, most commonly standing up.

Treatment

Medical management most commonly involves physiological methods including graduated exercise programs, high fluid and salt intake (not to be used in hyperadrenergic PoTS cases), and support tights. Triggers such as prolonged standing or sitting, alcohol, heat, and large meals should be avoided. Postural counter-maneuvers can abort a syncopal attack. Cognitive-behavioral therapy helps patients adjust to long-term illness. Drug treatment is aimed at increasing blood volume (fludrocortisone, desmopressin, erythropoietin), vasoconstriction (midodrine, methylphenidate, octreotide), reducing tachycardia (beta-blockers, ivabradine), improving central cardiovascular control (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, clonidine), and facilitating synapse transmission (pyridostigmine). The available drugs are all currently “off label” for this indication but may be medically appropriate.

As practicing chiropractic neurologists, our clinic sees many patients with dysautonomia. Many patients with dysautonomia may be diagnosed with anxiety, panic attacks, and/or chronic fatigue syndrome, yet the cause of these issues may be dysautonomia that has yet to be diagnosed. As a result of orthostatic intolerance, many patients can become wheelchair and/or bed bound. However, 80-90% of these patients typically respond to treatment and 60% will return to previous levels of functioning with the appropriate care.

Assessments

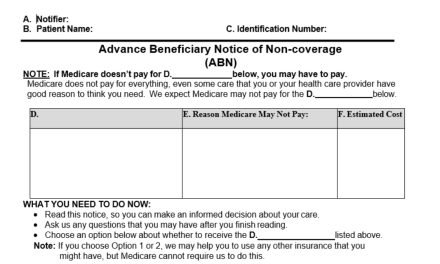

All of the patients we evaluate at our clinic undergo physical and neurological assessments ruling in/out any dysautonomia. This includes measuring and comparing blood pressure, heart rate, and oxygen perfusion/saturation with our patients sitting, lying supine, and standing up. We also measure blood pressure and oxygen perfusion index responses, comparing the left side of the body to the right side of the body. We also assess a variety of autonomic reflexes throughout the body.

Appropriate blood flow regulation is essential for appropriate function and healing. Therefore, it is imperative to identify and manage dysautonomia signs and symptoms with all patients. Our clinic provides specific physical and neurological rehabilitation for these patients with dysautonomia. This may include exercises to strengthen muscles and/or light aerobic exercise, non-invasive electric stimulation, transcranial photobiomodulation, non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation, vestibular rehabilitation, manual therapy, neurofeedback therapy, eye-head coordination exercises, tilt-table/orthostatic exercises, cognitive exercises, oxygen therapy, brain-wave synchronization therapies, normatec treatment, virtual reality training, nutritional/health coaching, and other types of rehabilitation.

Patients with dysautonomia may present with a long list of symptoms and diagnoses. Usually, the presentation involves multiple systems and must be assessed and treated in a comprehensive fashion. By combining physical and neurological rehabilitation, as well as co-managing with medical and mental health professionals, there is hope for many patients with dysautonomia who are currently living chronically ill and disabled.

References

Abed, Ball, Wang. Diagnosis and management of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Journal of Geriatric Cardiology. 2012;9:61-67.

Kavi et al. Postural tachycardia syndrome: multiple symptoms, but easily missed. British Journal of General Practice. 2012;62(599):286-287.

Martinez et al. Sympathetic nervous system dysfunction in fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, and interstitial cystitis. Journal of Clinical Rheumatology. 2014;20(3):146- 150.

Reichgott MJ. Clinical Evidence of Dysautonomia. In: Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, editors. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 3rd edition. Boston: Butterworths; 1990. Chapter 76. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK400/.