Case Study: Positive Valsalva and Kemp

I find case studies very interesting. I suspect that most physicians feel the same way. I find it even more interesting when the case involves the Chiropractic profession, and there is subsequently a significant impact on the patient’s life as a result of our intervention. Additionally, I am continually impressed by the quality of the physicians in our field and am privileged to work with some of the very best. The following case occurred earlier this year and is fairly representative of the benefit of imaging in the Chiropractic setting and demonstrates the service that an astute Doctor of Chiropractic can provide.

History:

A 53-year-old male construction worker presented to a private Chiropractic clinic complaining of acute, severe pain in his lower back, radiating down to the right buttock, hip, thigh, and calf. He denied any sensation of numbness or tingling, or loss of bowel or bladder control. He reported difficulty sleeping and an increase in pain with sitting and most movements. He reported that standing was the least painful position.

The pain began several days earlier while lifting and moving an old heavy television when he heard a ‘pop’ in his back and felt severe pain radiating down to his right hip and thigh. He denied any history of cancer or other significant health condition.

Physical Examination:

The examination revealed a positive Valsalva and Kemp’s on the right. All lumbosacral ranges of motion were limited and guarded with extension causing severe pain at 10 degrees. Toe walk was normal. However, heel walk revealed mild weakness on the right. Lower extremity sensation was normal to pinwheel examination, and the bilateral patellar and Achilles reflexes were absent. Bechterew’s test was positive on the right with the patient being unable to fully straighten his right leg while sitting due to pain.

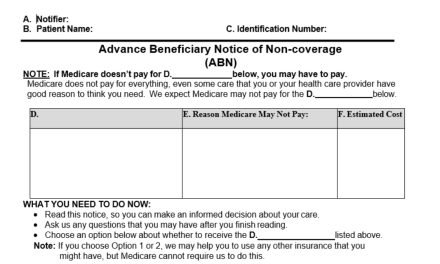

Imaging:

The plain films displayed in figures 1 and 2 were obtained on the day of presentation. There is lytic destruction of the right side of the L4 vertebral body and right pedicle as noted on the AP projection, figure 1. A subtle but definite degree of compression of the L4 vertebral body is identified on the lateral projection, figure 2.

Based upon the physical findings of the examination and the plain film findings of lytic destruction, it was deemed prudent to order an MRI examination of the lumbar spine. The patient needed to be prequalified by his health insurance company to be cleared for the MRI examination. Although there was initial resistance by the insurance company in allowing the MRI exam, the doctor was insistent with this case, and the patient was finally cleared for the exam.

Figures 3 and 4 are the sagittal T2 and fat-suppressed MRI images obtained thru the L4 level. Both images reveal signal intensity hyperintense to normal marrow consistent with marrow replacement and a degree of compression of the L4 vertebral body.

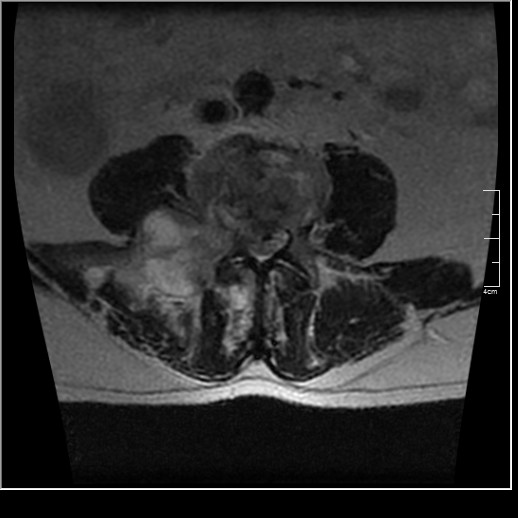

Figure 5 is a representative axial T2 image which shows to great advantage the destruction of the right pedicle and right inferior L4 facet, as well as, cortical destruction of the right half of the vertebral body. Also noted is a large right paraspinal heterogeneous soft tissue mass which extends out through the right intervertebral foramen. Cortical destruction of the posterior aspect of the vertebral body is present with a soft tissue mass that has resulted in marked compression of the thecal sac.

Discussion:

Metastatic bone tumors are much more common than primary malignant bone tumors overall, representing approximately 70% or all malignant bone tumors (1). The age of this patient would be more supportive of a metastatic lesion rather than an aggressive primary malignancy. The presence of the extensive soft tissue mass, however, is seen less often in metastatic lesions than in primary bone tumors. As a rule, uncommon presentations of common tumors are more common than common presentations of uncommon tumors. You may need to re-read that last sentence, but essentially a metastatic lesion, even though exhibiting a soft tissue mass, would still need to be considered more likely that a primary malignant bone tumor.

Once the MRI was read, the ordering physician was called by the radiologist to discuss the findings. The following day he was admitted for further evaluation. His evaluations included a neurosurgical consultation after which surgery was recommended. The patient refused any surgical intervention and decided to go home with pain medication. The patient was later diagnosed with primary esophageal carcinoma. The patient passed away approximately four months after his initial visit to the Chiropractic office.

This case demonstrates the extensive osseous involvement that may be present before symptoms become manifest. It is truly remarkable how adaptive the human body may be. To allow such destruction and yet be able to function until almost the very end is quite remarkable. This pathology really only becomes clinically evident when the structural integrity of the vertebra had been compromised to such a degree that compression fracture resulted. The case also demonstrates the ambiguity that may be present initially upon examination. This patient’s symptoms could have been explained on the basis of a disc herniation. Imaging was essential in arriving at the correct diagnosis.

I would like to thank Dr. Ralph Kruse DC, DABCO for furnishing this case and a portion of this text.

References:

Yochum and Rowe: Essentials of Skeletal Radiology. Philadelphia, Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2005.