Radiography of Viral or Secondary Bacterial Pneumonia

With the advent of the COVID 19 pandemic, it may be prudent to review the radiographic findings of viral or secondary bacterial pneumonia, which may be a complication of the infection. In this article, I will describe two cases in which pneumonia developed. To begin, I would like to review some of the recent Coronavirus data.

Coronaviruses are named for their crown-like appearance, consisting of surface spikes. The viruses can be categorized into 4 major groups (alpha, beta, gamma, and delta). Although most coronaviruses affect animals, they can be transmitted between animals and humans. Previously, two human coronaviruses have been documented to cause severe respiratory illnesses and even death. These viruses included Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV), which was first reported in 2012 in Saudi Arabia. The COVID-19 is the latest addition to this grou which and has been reported to have initially affected patients who worked at or lived around the local Huanan seafood wholesale market in China. Subsequently, cases were confirmed with no exposure to animal markets, indicating person-to-person spread of the virus.

Clinical Manifestations

The most common clinical manifestations include fever (83%), cough (82%), and shortness of breath (31%). For laboratory-confirmed cases, no specific treatment is available, and care is primarily supportive, with appropriate precautions to stop person-to-person transmission. The severity of the disease can range from asymptomatic and mild cases to acute respiratory distress syndrome and death.

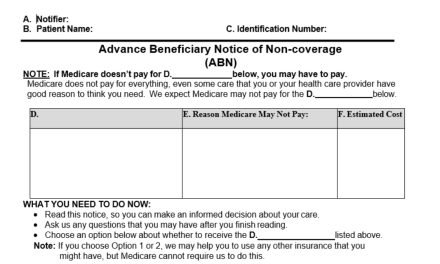

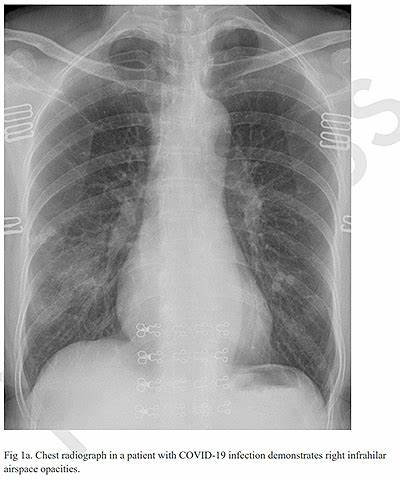

Chest radiography is typically the initial imaging modality used for patients with suspected COVID-19, although CT examination is more sensitive for early involvement (1). Chest radiographs may be normal in early or mild disease. Of patients with COVID-19 requiring hospitalization, 69% had an abnormal chest radiograph at the initial time of admission, and 80% had radiographic abnormalities sometime during hospitalization. Findings are most extensive about 10-12 days after symptom onset. The most frequent findings are airspace opacities, whether described as consolidation or ground-glass opacities. The distribution is most often bilateral, peripheral, and lower zone predominant. In contrast to parenchymal abnormalities, pleural effusion is rare (~3%). Figure 1 demonstrates subtle ground-glass opacity in the right lower lobe. More extensive involvement is noted in another patient (Figure 2) with bilateral areas of consolidation. The costophrenic angles remain sharp, indicating a lack of pleural effusion.

Case 1:

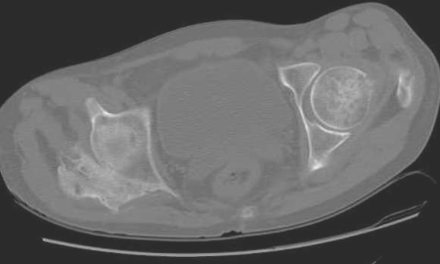

A 59-year-old female presenting with fever and chills. She had no known prior exposure to affected individuals; however, she had recently traveled from London, England. Chest radiograph (Figure 3) at presentation showed patchy right lower lobe ground-glass opacities. Figure 4 is a chest CT of this patient demonstrating the same ground glass appearance in the posterior aspect of the right lower lobe.

Case 2:

A 62-year-old female presented 7 days after contact with neighbor who had recently tested positive for COVID-19. She began experiencing a cough and fever. Initial radiographs were unremarkable; however, chest CT showed a small solitary nodular ground-glass opacity in the left upper lobe (Figure 5). 3 days later, a follow-up CT showed multifocal nodular and limited peripheral ground-glass opacities involving both upper lobes (Figure 6, arrows). A third CT performed 5 days from presentation (Figure 7) showed progressive consolidation in the right lower lung.

Imaging findings are generally non-specific for pneumonitis involved with COVID-19. Findings must be correlated with a history of exposure to a known positive testing individual, history of travel to an area of known infection, patient symptoms and more specifically a positive COVID-19 test. Nodular and peripheral ground glass opacities in the proper setting should raise suspicion of accompanying pneumonitis.

References:

1. Radiology: Cardiothoracic Imaging Vol. 2, No. 1