Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV)

Vertigo affects as many as 35% of adults aged 40 years or older in the United States—approximately 69 million Americans—have experienced some form of vestibular dysfunction (1). According to the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), a further 4% (8 million) of American adults report a chronic problem with balance, while an additional 1.1% (2.4 million) report a chronic problem with dizziness alone (2). Eighty percent of people aged 65 years and older have experienced dizziness (3); and BPPV, the most common vestibular disorder, is the cause of approximately 50% of dizziness in older people (4). Overall, vertigo from a vestibular problem accounts for a third of all dizziness and vertigo symptoms reported to health care professionals (5). A healthy understanding of the causes and treatment of this condition can help you to better assist the patient and establish you as the local expert in the treatment of this common condition.

Typical symptoms a patient may present to the office with will include:

- Dizziness when turning in bed,

- Dizziness precipitated by sudden head rotation,

- Dizziness precipitated by sitting up from a recumbent position,

- Lightheadedness,

- Nausea, and

- A sensation of surroundings moving.

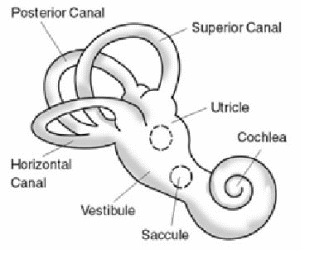

Understanding BPPV requires a quick review of the anatomy of the vestibular cochlear apparatus, more commonly called the vestibular labyrinth. This structure, found in the inner ear, can be divided into two areas: the semicircular rings and the vestibule (the region containing the utricle and saccule). The fluid is contained within this structure and its movement is monitored by fine hairs. When fluid moves in the semicircular canals it gives the sensation of rotational movement. Fluid movement in the vestibule produces the sensation of other motion (front to back, side to side, up and down) (6). The vestibule also contains crystals that produce the sensation of motion, and when those crystals become displaced following trauma or infection, they may move into the semi-circular canals and produce dizziness with little movement of the head. When this happens the patient may experience the sensation of spinning when turning in bed, looking up, or getting up or down from a recumbent position.

Diagnosis:

Diagnosis for BPPV can be made using a test called Dix-Hallpike maneuver. This test is performed with the patient seated upright on an examination table:

- The head is turned 45 degrees to the side and extended 20 degrees.

- Then the patient is quickly moved to a supine position while this head position is maintained for at least 30 seconds.

The practitioner should observe the eyes for signs of nystagmus (involuntary side to side eye movement). If no nystagmus is observed, then the test may be performed on the opposite side. If nystagmus is observed, note the side to which the head is turned. This indicates the affected side. Nystagmus due to BPPV should resolve within approximately a minute. If symptoms remain following several minutes of the test, or if other aberrant eye motions are observed, this may indicate other possible problems that may require further examination, testing or possible referral (7).

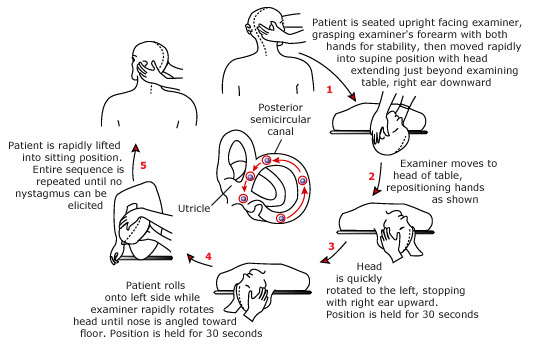

Treatment:

Eply’s maneuver is a highly effective treatment for BPPV. Many studies, including randomized control trials, have found success rates as high as 60% after only one treatment and 95% after three treatments (8). Eply’s Maneuver is performed simply as demonstrated in the diagram below. However, holding a tuning fork to the mastoid process has not shown improvement in outcomes when performing this procedure (9).

REFERENCES

- Agrawal Y, Carey JP, Della Santina CC, Schubert MC, Minor LB. Disorders of balance and vestibular function in US adults. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(10): 938-944.

- National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD). Strategic Plan (FY 2006-2008). Available at: www.nidcd.nih.gov/StaticResources/about/plans/strategic/strategic06-08.pdf. Accessed May 20, 2010.

- Ator GA. Vertigo—Evaluation and Treatment in the Elderly. Available at: www2.kumc.edu/otolaryngology/otology/VertEldTalk.htm. Accessed May 20, 2010.

- Fife TD, Iverson DJ, Lempert T, Furman JM, Baloh RW, Tusa RJ, Hain TC, Herdman S, Morrow MJ, Gronseth GS. Practice parameter: therapies for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurol. 2008;70:2067–2074.

- Neuhauser HK, Radtke A, von Brevern M et al. Burden of dizziness and vertigo in the community. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(19):2118–2124.

- Benign Paroxysmal positional vertigo. Mayo Foundation for medical education and research. http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/vertigo/DS00534/DSECTION=causes. Accessed July 6, 2012.

- Dix-Hallpike test for vertigo. eMedicineHealth Medical Reference from Healthwise. http://www.emedicinehealth.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=138476&ref=129502. Accessed July 6, 2012.

- Effectiveness of Eply’s Maneuver in the treatment of Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo. Bahrain Medical Bulletin, Vol 8, No 1, March 2008.

- Hain, TC. http://www.dizziness-and-hearing.com. Efficacy of vibration in the Eply’s maneuver for the treatment of BPPV. Accessed July 6, 2012.