Loose Body Formation Associated with Degenerative Joint Disease and as a Primary Disorder

Calcification/ossification of cartilaginous bodies within a synovial joint is not a rare phenomenon. This may occur secondarily as a result of degenerative joint disease or as a primary entity. Technically this is referred to as “synoviochondrometaplasia.” As the name implies, this represents a metaplastic process involving the synovium of the joint, in which cartilaginous loose bodies form within the joint. This is a form of benign neoplasia. These cartilage bodies may subsequently calcify and ossify, forming a density that may be visualized on x-ray. Some other terms that have been applied to this disorder are “joint mice,” “osteochondromatosis” and “synovial osteochondromatosis”(1).

Symptomology

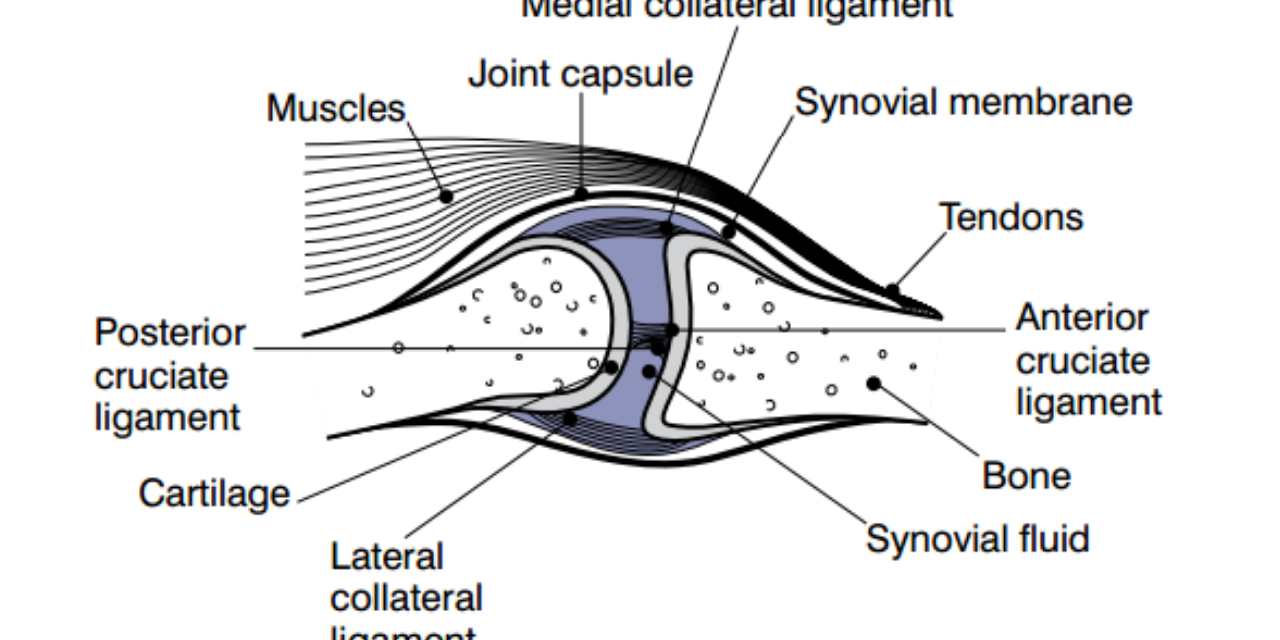

Symptomatically, the patient may suffer the type of pain typically seen in degenerative joint disease; however, this may be accompanied by joint swelling, limited range of motion, joint locking, and crepitus on palpation. The presence of these bodies within the joint will lead to an acceleration of degenerative changes or the initiation of degenerative change, if in the primary form. The primary form arises without an identified episode of macrotrauma; however, repeated microtrauma may play a role in this etiology. In either primary or secondary form, the pathophysiology is the same. As noted above, this represents a benign neoplasia, but there are rare reports of malignant transformation.

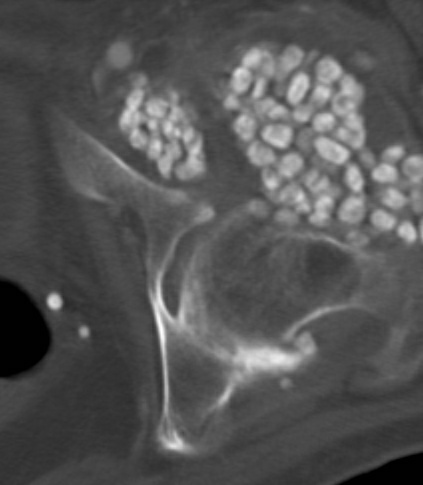

The process begins with cartilaginous bodies; thus, x-rays obtained early may fail to show any abnormality. Large cartilaginous masses may be seen indistinctly within a joint. In the cartilaginous phase, MRI will demonstrate their presence, as will arthrograms. Once the cartilage begins to calcify and ossify, the bodies will be able to be identified on x-ray and CT. The size of the individual loose bodies may range from 1 to 20 mm. The calcifications have been known to coalesce and form large masses, which have been reported as up to 20 cm in diameter. The individual loose bodies are well-defined and rounded in contour. They are generally uniformly dense but may have laminations or stippling within them. The pressure of the loose bodies against adjacent bone may result in pressure erosion of the bony cortex. In the hip, this may produce an apple core deformity of the femoral neck. The pressure erosions will spontaneously resolve if the loose bodies are surgically removed. Common areas of involvement include the hip, knee, ankle, and elbow, with less common involvement in the shoulder, wrist, hand, and foot. Differential diagnosis would include os fabella, other sesamoid bones, pseudogout, synovioma, chondrosarcoma, pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS), and tuberculosis.

Figure 1 demonstrates multiple loose bodies within the posterior aspect of the knee joint. In figure 2 the single density is imbedded within the posterior joint capsule, which represents an os fabella. The os fabella is a sesamoid bone in the attachment of the lateral head of the gastrocnemius muscle and should not be confused with a loose body. The loose bodies may become quite large, as seen in figure 3.

Figure 4 demonstrates loose bodies within the hip and the subsequent formation of pressure erosions of the femoral neck, yielding an apple core deformity. There are multiple calcified bodies in the hip on the CT image, figure 5.

Figure 6 demonstrates bodies in the elbow, which is a common site of involvement.

In figure 7 we see multiple bodies, not just in the glenohumeral joint, but also extending up into the subcoracoid bursa, because this bursa communicates with the glenohumeral joint.

The calcified bodies present in synoviochondrometaplasia need to be surgically removed. If left in place, there will be premature and excessive degeneration of the joint.

References

1. Yochum T.R., Rowe L.J.: Essentials of Skeletal Radiology, ed 3. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.