Imaging Diagnosis of Spinal Infections

Infections of the skeleton have existed since the dawn of man and can be found in Egyptian mummies as well as other preserved archeological specimens. Spinal infection while not common [approximately 10% of all bone infection (1)] may result in significant morbidity to a patient and in rare cases mortality. The advent of antibiotics has markedly decreased the rate of sepsis and subsequent mortality. Suppurative or pyogenic infections of the spine are acute conditions and are somewhat different in presentation, appearance and prognosis from non-suppurative infection. Suppurative infections are most commonly caused by staphylococcus aureus whereas non-suppurative are often due to organisms such as tuberculosis. This article will focus on suppurative infection. These have become more common today with the increased prevalence of immunocompromised states. They are also seen in IV drug abusers, alcoholics and newborns. Patients that have had recent surgery or who have an active infection elsewhere in the body are also at increased risk for spinal infection.

Hematogenous spread is the most likely route for an organism to enter the vertebral body. Direct implantation is another method of seeding the spine and may result from surgery or a deep penetrating wound. Spread of infection from the surrounding soft tissues to the spine is also a possible route of entry. When the organism infects the bone it results in an inflammatory reaction which increases the intramedullary pressure and compresses surrounding capillaries. This produces bone infarction with subsequent osteolysis. In the adult spine, the infection often begins adjacent to a vertebral endplate and then extends into the disc and often the opposing endplate. Children and teenagers typically involve the intervertebral disc first and then spread into the bone. A radiographic hallmark that helps differentiate a neoplastic cause of osseous destruction from infection is that most neoplasms do not cross the disc space whereas infections will.

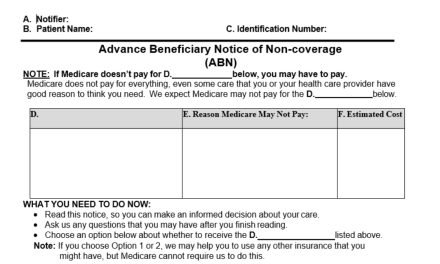

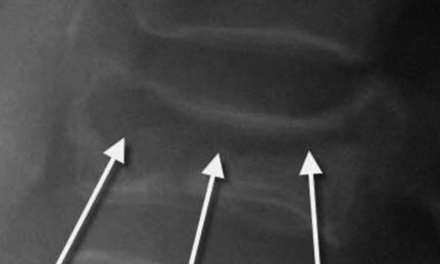

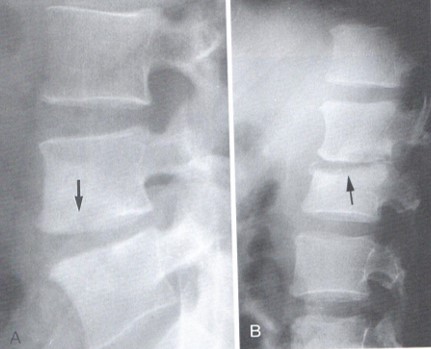

The earliest sign of spinal discitis/osteomyelitis is a decrease of disc spacing. Since disc thinning is a very common finding seen in spinal degeneration, care must be taken to examine the vertebral body looking for endplate destruction or osteolytic lesions in the adjacent vertebral body (figure 1). In figure 1A there is a moderate reduction of lumbar disc height with subtle destruction of the superior endplate. Figure 1B demonstrates more extensive disc thinning and endplate destruction in another patient. A loss of disc spacing in a child or teenager should be taken as a sign of pathology until ruled out. Intradiscal gas is not a common finding on plain film x-ray. There will likely be adjacent soft tissue swelling which may manifest as an increased prevertebral space in the cervical spine. In figure 2 the initial radiograph on the left was interpreted to represent extensive multilevel degenerative disc disease. Careful inspection of the C6-C7 level reveals complete loss of disc spacing with minimal marginal osseous vertebral body proliferation. The right-sided image was obtained 1 month later and reveals obvious osseous destruction at C6-C7 with an increase in the prevertebral soft tissue space. A retrospective evaluation of the first radiograph reveals less osteophyte formation than would be expected with this degree of disc loss if simple disc degeneration was the actual etiology. There is also a lack of endplate sclerosis which is seen in the degenerated segments above this level. (Figures 1 and 2 are courtesy of Yochum and Rowe “Essentials of Skeletal Radiology”). Figure 3 demonstrates a marked degree of endplate destruction on both sides of the disc at a lower thoracic level. Paraspinal soft tissue swelling in the thoracic spine may result in displacement of the paraspinal lines and in the lumbar spine cause distortion of the psoas shadows.

![Spinal infection while not common [approx. 10% of all bone infection] may result in significant morbidity to a patient and in rare cases mortality.](https://statusfidashboard.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2019/06/figure_2-_greg.jpg)

Although spinal infections rarely result in death in todays healthcare environment, there may still be significant morbidity and serious consequences may still occur if diagnosis is delayed. MRI or CT may be employed to help evaluate the possibility of spinal infection. In the next article we will explore the findings of spinal infection on advanced imaging.

References

- Yochum T.R., Rowe L.J.: Essentials of Skeletal Radiology, ed 3. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

Dr. Gregerson serves as the president of the American Chiropractic Board of Radiology and is chief radiologist at Gregerson Radiology Consultants, a private consulting practice, www.mychiropracticradiologist.com