Bertolotti Syndrome: A Potential Cause of Low Back Pain

As spinal specialists, it is common to encounter a lumbosacral transitional vertebrae (LSTV) on x-ray or advanced imaging. Since these congenital anomalies are commonly seen in practice, it is easy to assume they are clinically insignificant and not consider this finding as a potential cause of the patient’s symptoms. While this is often the case, we now understand that LSTV can be symptomatic, depending upon the type and other factors. Additionally, it is important to note and accurately describe this variation in radiology reports and patient notes to avoid an intervention or surgery at an incorrect level. In this article we will look at a case of a LSTV and discuss the associated radiographic and clinical findings can that occur with the varying types.

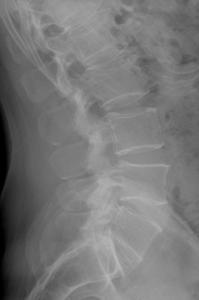

Our patient is a 35-year-old male with low back pain, accompanied by left lower extremity radicular symptoms.

We can see that the L5 vertebral segment is transitional with a broadened left transverse process that forms an anomalous articulation with the sacrum. The right transverse process is normal. The L5/S1 disc does not show signs of degeneration and is generally preserved, but the L4/5 disc level shows early degenerative signs such as spondylophyte formation. As will be discussed in the next section, this is a Castellvi type IIa lumbosacral transitional vertebrae.

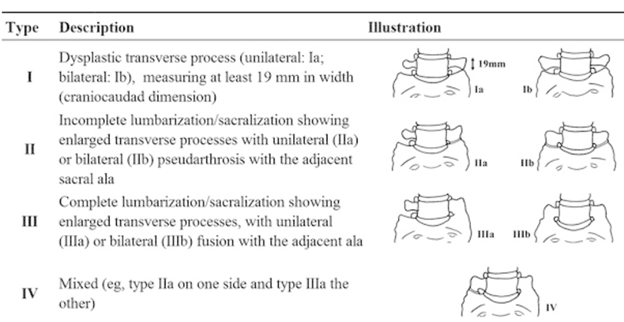

The Castellvi classification is the most commonly used classification system to describe lumbosacral transitional vertebrae and consists of four types, as described in Figure 1 below.

Most literature states that type I is typically asymptomatic. However, the association between low back pain/radicular symptoms and types II-IV are controversial and have been both repeatedly supported and disputed since Mario Bertolotti first described the association in 1917. The term Bertolotti syndrome has since been introduced to describe the radiographic and clinical findings that are associated with these particular types of LSTV.

The low back pain in Bertolotti syndrome is thought to be of varying etiologies and arises from different spinal locations to include: 1) disc, spinal canal, and posterior element pathology at the level above the LSTV; 2) degeneration of the anomalous articulation between the LSTV and the sacrum; 3) facet joint degeneration contralateral to the unilateral fused or articulating transverse process; and 4) extraforaminal stenosis secondary to the presence of the broadened transverse process(2).

The symptoms associated with Bertolotti syndrome likely occur due to the altered biomechanics resulting from the anomalous relationship between the LSTV and the sacrum. First, there appears to be hypomobility at the level between the LSTV and the sacrum, resulting in disc preservation and decreased disc pathology at the disc level below the LSTV. This is likely due to the lack of mobility at the fused transitional level or the decreased mobility at a partially fused or anomalously articulating vertebrae leading to stabilization at this level. The stabilization at the level below the LSTV leads to hypermobility at surrounding articulations, including at the level above the transitional segment, the anomalous articulation itself, or the contralateral facet joint. The increased hypermobility at these regions leads to accelerated degeneration (2).

While not all patients’ symptoms follow the expected pattern of pain based on the anomaly, some symptom generalities have been observed, based upon the type of LSTV. Skeletal scintigraphy has shown that there is increased radiotracer uptake (indicating inflammation) at the pseudoarticulation in the Type IIa patients. If the transverse process was fused to the sacrum (Type IIIa), high uptake was noted at the level above or at the contralateral facet (4). MRI has shown extraforaminal stenosis leading to nerve root entrapment and compression between the hyperplastic transverse process and the sacrum.

Treatment can vary widely, depending upon symptoms and anatomy involved. Conservative care should always be the first consideration when treating a patient with symptomatic LSTV. If the patient is unresponsive to conservative care, non-surgical options include local injection of anesthetic and corticosteroids within the pseudoarticulation or contralateral facet joint (depending upon the pain generator). In select patients, surgical management may be indicated and may include partial transverse process resection and/or posterior spinal fusion.

In conclusion, a knowledge of these commonly encountered anomalies is vital to understanding the confounding symptoms that may occur in patients with a LSTV. Knowledge of the anatomy resulting in increased regions of biomechanical stress based upon the type of LSTV will be helpful in the management of these patients.

References

1) Nakajima A, et al. The prevalence of morphological changes in the thoracolumbar spine on whole-spine computed tomographic images. Insights Imaging. (2014) 5:77–83.

2) Konin GP and Walz DM. Lumbosacral Transitional Vertebrae: Classification, Imaging Findings, and Clinical Relevance. American Journal of Neuroradiology. November 2010, 31 (10) 1778-86.

3) Connolly LP, d’Hemecourt PA, Connolly SA, et al. Skeletal scintigraphy of young patients with low-back pain and a lumbosacral transitional vertebra. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:909–14.