Vertebral Body Compression Fracture, New vs Old

Something that I am often asked is to determine whether a compression deformity in a vertebral body is new or old. Compression fractures are relatively common, particularly with increasing patient age. It is always important to distinguish between a recent fracture and one that has been present for a long period of time. The possible underlying cause of a fracture must be found if there is one. Frequently a vertebral body compression fracture is a result of relatively normal stresses on an osteoporotic bone. This is seen commonly in post-menopausal women. Even in these cases though an underlying cause such as metastatic disease must be ruled out. If a fracture is recent, this is more problematic.

Radiology

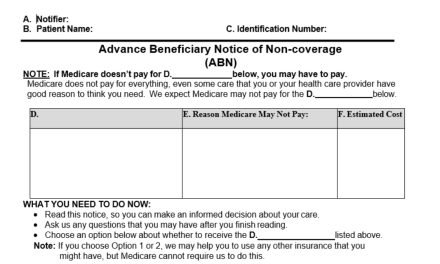

Radiographically, an acute fracture may manifest rather pathognomonic findings on plain film x-ray. These include a wedge deformity, step defect of the anterior cortex, disruption of a vertebral endplate or a zone of condensation in the vertebral body (1). Acute fractures are not always this clear cut, however. A recent history of trauma may be of benefit however sometimes this is a red herring, and there may be an old fracture present that had gone undiagnosed. Old films of the area may be of great benefit, however often these are not available. Various forms of advanced imaging can provide much needed information to determine if a fracture is new or old.

CT Scans

CT scans can in some cases provide information to help make this determination, however, may suffer from some of the same inadequacies as plain film. CT is x-ray after all and although it allows imaging in 3 dimensions no physiologic data is obtained in a CT scan. Some fracture margins may be better seen with CT and if there is a comminuted or complex fracture pattern, CT would show this to great advantage. Overall however it does not usually contribute much information to answer the question of new vs old.

Radionuclide bone scans provide some physiologic information, however, can be relatively non-specific unless conforming to an expected configuration.

MRI

MRI provides quite a lot of physiologic information as well as anatomical information. Typically, MRI images in a chronic (old) fracture will yield marrow signal intensity that is isointense to normal marrow seen in adjacent vertebral bodies. In acute and even subacute fracture the marrow will demonstrate increased signal intensity on the T-2 or fat-suppressed images and hypointense signal on the T-1 weighted images. Usually, some areas of normal marrow signal intensity will remain within the vertebral body in a benign compression fracture (2). If there is marrow infiltration such as that seen in metastatic disease, no normal narrow signal will remain. It is possible to see a step defect of the cortex anteriorly and wedge deformities of the vertebral bodies with MRI as well.

Figure 1 demonstrates an x-ray of a compression deformity of a lumbar vertebral body that manifests some of the radiographic criteria of an acute fracture. There is a zone of increased density (zone of condensation) paralleling the superior vertebral endplate. There is a decrease in the vertebral body height and a slight step off of the anterior vertebral body cortex at the superior endplate.

Figure 2 reveals an anterior compression of the L1 vertebral body with a separate fracture fragment as well as disruption of the superior endplate. In addition, there is a degree of retropulsion of the posterior aspect of the vertebral body. CT is superior for displaying these kinds of detailed anatomic abnormalities.

Figure 3 demonstrates an MRI examination of a more subtle vertebral body compression anteriorly at L1. The alteration of signal intensity, hyperintense to normal marrow on T-2 and hypointense on T-1 means that this is an acute process. This does not represent an old fracture.

In conclusion, MRI is the best imaging modality available for determining acute vs old compression fractures of the vertebral bodies.

References:

- Yochum T.R., Rowe L.J.: Essentials of Skeletal Radiology, ed 3. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005

- Renfrew D.L.: Atlas of Spine Imaging, Philadelphia, Elsevier Science, 2003