Thoracic Kyphosis and Forward Head Posture

The Effects of Thoracic Kyphosis and Forward Head Posture on Cervical Range of Motion in Older Adults

Have you ever read a piece of research that confirmed the efficacy of chiropractic and thought to yourself “Of course that is the result, what else were you expecting?” I’m guessing that you have done that numerous times because you are a chiropractic physician. There are many articles available that demonstrate the effectiveness of the services we provide, whether it involves cost savings, rapid reduction of pain, etc. I recently came across one of these articles in the past year that I thought I would present in this journal. The information from the article may not be “earth-shattering,” but it does provide evidence for the approach we may take when addressing a patient with forward head posture (FHP). In fact, the reason I decided to share the article is that I was able to use the information from this article in a recent deposition.

In this article from the Manual Therapy Journal, we will look at the effects of thoracic kyphosis on forward head posture. Every day, we see patients with hyperkyphotic spines and FHP. When treating neck dysfunction/pain, we naturally assume and have been taught that there is a relationship between both FHP and thoracic kyphosis, but what drives that dysfunction? FHP? Or does thoracic kyphosis drive FHP, which drives cervical dysfunction? This article attempts to answer that question.

51 adults, average age 66, with cervical pain with or without referred pain, numbness or paraesthesia, participated in the study. The exclusion criteria included a significant list, which included neuromuscular disorder, moderate and severe scoliosis, and whiplash injury.

The authors named 4 variables to the study: age, gender, body mass and neck disability index (NDI), which was used to measure patient disability. Thoracic curvature was measured using the flexicurve method, which has been documented as an accurate technique for measuring the thoracic curve: however it is beyond the scope of this article to review the technique. FHP was measured using digitized, lateral-view photograph of the subject in his/her normal standing posture. The authors then quantified the craniovertebral angle (CVA) to determine the amount of FHP, a lesser CVA indicating a greater amount of FHP. Finally, the authors measured cervical range of motion using the cervical range-of-motion device. The measurements obtained for ROM were: total active cervical flexion range in upright sitting; total active cervical rotation in upright sitting; and passive upper cervical rotation in available full flexion in supine. During testing of rotation, the patient’s thoracic spine was securely strapped to the chair to limit any thoracic spine movement.

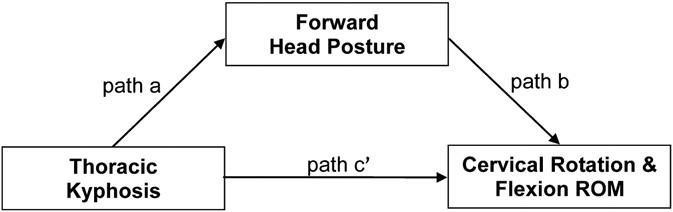

The authors used a mediation model (fig. 5 from article) to determine whether FHP carried the influence of thoracic kyphosis on cervical ROM. A mediation model is one that seeks to identify and explicate the mechanism or process that underlies an observed relationship between an independent variable (thoracic kyphosis) and a dependent variable (Cervical rotation & flexion ROM) via the inclusion of a third explanatory variable, known as a mediator variable (FHP). Rather than hypothesizing a direct causal relationship between the thoracic kyphosis and the cervical ROM, a mediational model hypothesizes that the thoracic kyphosis influences the FHP, which in turn influences the cervical ROM. Thus, the mediator variable serves to clarify the nature of the relationship between the independent and dependent variables.

Results from the study revealed a positive association between the thoracic kyphosis and FHP, in addition to finding that FHP limits cervical ROM. As for the effect of thoracic kyphosis on cervical ROM, the authors conclude that thoracic kyphosis may be the driver in FHP, therefore making addressing the thoracic spine of utmost importance. The authors go on to state that the study supports the regional independence theory by Wainner2 et al. in that” seemingly unrelated impairments in a remote anatomical region may contribute to, or be associated with, the patient’s primary complaint.”

From the clinical perspective, this paper is not ground breaking by any means; in fact, I would argue that this is common knowledge to chiropractic physicians. However, this paper does support our treatment model of addressing the thoracic spine when working with patients with cervical complaints of pain, lack of motion, stiffness, etc. As the authors go on to conclude, by addressing the thoracic spine, we would be taking an “upstream” approach in addressing the patient’s problem.

References:

- Quek J, Yong-Hao P, Clark RA, Bryant AL. Effects of thoracic kyphosis and forward head posture on cervical range of motion in older adults. Manual Therapy 2013;18:65-71.

- Wainner RS, Whitman JM, Cleland JA, Flynn TW. Regional interdependence: a musculoskeletal examination model whose time has come. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 2007;37(11):658e60.