Inflammatory Arthropathies and Increased ADI

One of the first findings that we learn to recognize in the radiographic evaluation of the cervical spine is an increase in the atlanto-dental interspace (ADI). This is often the result of an inflammatory arthropathy, with rheumatoid arthritis being the major cause. A failure to make this finding may lead to serious consequences if the patient is subjected to cervical spinal manipulation.

The normal width of the ADI is less than 3.5 mm in an adult and up to 5.0 mm in a child. If the measurement is in excess of this amount, we should suspect that there is ligamentous compromise of the transverse ligament, which normally acts to restrain posterior translation of the dens.

The transverse ligament may be compromised if an inflammatory process occurs in the synovium at the atlanto-dental articulation. Rheumatoid arthritis results in synovitis with the subsequent formation of pannus which is a vascular granulation tissue. The pannus will result in osseous erosion and destruction of cartilage (1). Eventually the joint undergoes progressive fibrosis and possible osseous fusion. Erosions of the dens, when progressive, may result in its complete dissolution. The transverse ligament will become stretched from the pressure of the distended synovium. The attachments of the ligament may also loosen due to decalcification at the attachment sites. The atlanto-axial subluxation that develops may be made worse by cranial settling due to the cartilage thinning at the occiput-C1 and C1-C2 joints. In this case, the dens may protrude into the foramen magnum and result in neural compression. Other inflammatory arthropathies that may result in a similar appearance at the atlanto-dental interspace are ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, Reiters syndrome, and systemic lupus erythematosus. All of these conditions may result in a similar inflammatory sequence. Other non-inflammatory causes of an increased ADI include Down syndrome and ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL).

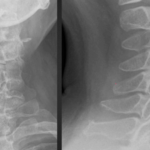

Plain film x-ray is useful in detecting an increase in the ADI and bony erosions. Figure 1 demonstrates an increase in the ADI with osseous erosion of the dens. The anterior translation of the posterior arch of C1 may impinge upon the central canal and result in neural compression. In some cases, flexion and extension views may be necessary to demonstrate the increase in ADI. An advanced imaging modality such as MRI provides superior soft tissue detail and can actually visualize the pannus. Figure 2 demonstrates pannus anterior to the dens with osseous erosion. The arrow points to the intermediate signal intensity pannus on this T-2 weighted mid sagittal image.

Reporting on the cervical spine in a patient with known rheumatoid arthritis or one of the seronegative spondyloarthropathies should include a description of the cervico-cranial relationships, including settling of the skull base around the cervical spine, as well as evaluation of the atlanto-dental interval (2). On MRI examination, evaluation of the brainstem and spinal cord is required, specifically looking for areas of increased signal on the T-2 weighted images. These findings may be present due to neural compression. Figure 3 demonstrates cranial settling with intrusion of the dens through the foramen magnum that displaces the medulla posteriorly. The dens labeled arrow 1 in this image is seen with its tip superior to the clivus, labeled with arrow 2. This patient has undergone posterior decompression surgery, as manifested in this image be the lack of visualization of the posterior arches at C2, C3, and C4.

In conclusion, evaluation of the ADI on the lateral cervical film may provide you with information that could help you prevent a neurologic episode due to spinal cord or brainstem contusion caused by aggressive cervical manipulation.

References:

- Yochum T.R., Rowe L.J.: Essentials of Skeletal Radiology, ed 3. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

- Renfrew D. L.: Atlas of Spine Imaging, Philadelphia, Saunders, 2003