Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome and the Dorsiflexion-Eversion Test

Attendees of the recent ICS general membership meeting at the Naperville Fall convention were privileged to hear one of our profession’s finest leaders share some particularly inspiring commentary. Dr. David Flatt, our outgoing ICS President, acknowledged the challenges that we as a profession face. He also reminded us that we are not the first generation of DC’c to struggle, i.e. very few of us have been jailed for “practicing medicine without a license.” Our predecessors worked hard to afford you and I the opportunities we enjoy today, and it is not the time to quit. His poignant, impromptu remarks were inspired by a bumper sticker that read: “Are you going to cowboy up, or just lie there and bleed?”

We have a responsibility to act now. In addition to supporting state and national associations, one paramount way to ensure our success is to provide a level of compassion and care not available elsewhere. Continually sharpening our skills and diagnostic abilities in order to provide affordable and effective treatment is appealing to patients and payors alike. I hope the following information on tarsal tunnel syndrome will help with your personal quest for excellence.

Introduction

Tarsal tunnel syndrome, first described in 1962, is a relatively common compression neuropathy of the posterior tibial nerve as it passes through the tarsal tunnel. Tibial nerve compression results in pain and/or paresthesia radiating into the plantar arch and heel. Tarsal tunnel syndrome may be under-diagnosed as it sometimes mimics plantar fasciitis or heel spurs.

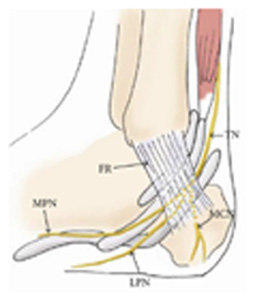

An understanding of relevant anatomy and pathomechanics may assist in accurate diagnosis (see fig. 1). The tarsal tunnel is formed by the flexor retinaculum (FR), which extends posteriorly and inferiorly from the medial malleolus. The tarsal tunnel houses the tendons of the flexor hallucis longus, flexor digitorum longus and tibialis posterior in addition to the posterior tibial artery and nerve (TN). As the posterior tibial nerve traverses the tunnel it divides into three branches: the lateral plantar nerve (LPN), the medial plantar nerve (MPN) and the calcaneal nerve (MCN). Incidentally, chronic compression of the medial plantar branch is called “Joggers Foot:” and is more common in ballet dancers and distance runners.

Causes and Symptoms

The tarsal tunnel has a variable volume, dependant upon the position of the foot. A valgus deformity of the foot causes diminished cross-sectional area and increased tensile load to the tibial nerve. (1) Trepman et al measured pressures within the tarsal tunnel in various foot positions and found an almost 30 fold increased pressure with pronation as compared to neutral. (2) Since overpronation is often present bilaterally, tarsal tunnel syndrome commonly affects both feet.

Other causes of tarsal tunnel include trauma (17%) or varicosities within the tunnel (13%). Tenosynovitis or inflammation of another local tissue may cause nerve compression. Exostosis from osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis may contribute, as do space-occupying lesions like cysts, ganglions or perineural fibrosis. (3) Co-existing polyneuropathies like alcoholism, diabetes and thyroid disorders may be superimposed on entrapment neuropathies.

There is a slightly higher incidence of tarsal tunnel in females as compared to males (3). Transitioning from high heels to flats on weekends is suspect.

Symptoms of tarsal tunnel include numbness, pain or paresthesia in the plantar arch and heel. The discomfort is often described as “burning”. Symptoms may increase with prolonged standing, running or exercise. Forty-three percent of patients report pain that is worse at night. (4) Severe presentations may exhibit weakness of the intrinsic foot muscles although this may be difficult to ascertain without nerve conduction testing.

Symptoms can occur suddenly from trauma or gradually from weight-bearing overuse type injuries. Symptoms may present as part of the “Heel Pain Triad”: the combination of plantar fasciitis, posterior tibial tendon dysfunction, and tarsal tunnel syndrome. Researchers postulate that a failure of the “static” plantar fascia combined with a “dynamic” failure of the posterior tibial tendon results in a traction injury to the tibial nerve. (5)

Diagnosis

Clinical evaluation often demonstrates a positive Tinel sign, elicited by tapping posterior to the medial malleolus. The patient may report tenderness to palpation over the tarsal tunnel and manual compression for 30 seconds sometimes reproduces the chief complaint. The patient may have diminished sensitivity to pinwheel or light touch in the distribution of the tibial nerve. The loss of two-point discrimination on the plantar surface of the foot is the first and most sensitive sensory assessment and may be used to monitor progress. Two-point discrimination can help determine which branch of the plantar nerve is compressed.

The Dorsiflexion-Eversion test is a useful assessment for tarsal tunnel. (6) As the name implies, this test is performed by placing the patient’s foot into dorsiflexion and eversion for 15 seconds while maintaining extension of the metatarsophalangeal joints. (Fig 2) Reproduction of plantar parasthesia during this test, although not pathognomonic, is an overwhelmingly positive sign of tarsal tunnel. (7)

Electrodiagnostic testing is not generally required unless motor involvement is suspected. If necessary, EMG/NCS can help to differentiate nerve entrapment from radiculopathy or peripheral neuropathy. Radiographs can be performed if a stress fracture, osseous lesion or exostosis is suspected.

Management and Treatment

The goals of management are first to reduce pain and inflammation and second to correct biomechanical dysfunctions such as overpronation, allowing the return to full activity. Initial treatment may include reassurance, rest, ice, anti-inflammatory modalities, and NSAIDs. Early correction of overpronation is critical. Individual needs vary from over-the-counter arch supports to custom orthotics. Consultation about footwear should include advice to discontinue wearing high heels (although a slight heel may actually improve symptoms) and consideration of a motion control shoe to prevent pronation.

Soft tissue techniques like Graston or Active Release may be helpful to release myofascial adhesions in or near the tarsal tunnel, although some discretion is necessary to avoid further trauma to the nerve. Hypertonicity and trigger points in the gastroc/ soleus are common and may benefit from fascial stripping. Stretching of the calf muscles as well as the plantar fascia can be implemented with prudence as dorsiflexion becomes more tolerable.

Strengthening of the tibialis posterior will help support the arch and may be accomplished by having the patient sit with the affected ankle crossed at the knee, placing a resistance band over the affected forefoot-secured beneath the other foot, and moving affected foot “up” into inversion and slight dorsiflexion. Manipulation may be beneficial to re-establish normal motion to fixations in the cuboid and talonavicular joint, (8) as well as associated spinal segments.

Failure of conservative treatment requires further diagnostic workup and consideration of referral to a podiatrist. Surgical management may include microsurgical decompression. Fortunately, most cases of tarsal tunnel will respond to clinically sound treatment and advice, making tarsal tunnel syndrome yet another opportunity for DC’s to demonstrate our excellence in conservative management of musculoskeletal problems.

References

- Daniels TR, Lau JT, Hearn TC. The Effects of Foot Position and Load on Tibial Nerve Tension. Foot Ankle Int. Feb 1998;19(2):73-8

- Trepman E, Kadel NJ: Effect of Foot and Ankle Position on Tarsal Tunnel Compartment Pressure. Foot Ankle Int. 2000: Nov 20(11):721

- Lau J, Daniels T. Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome: a Review of the Literature. Foot Ankle Int. 1999;20(3):201-209

- Mondelli M, Morana P, Pauda L. An Electrophysiological Severity Scale in Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome. ACTA Neurol Scand. 2004;109:284-289

- Labib, SA et al. Heel pain triad (HPT): The Combination of Plantar Fascitis, Posterior Tibial Tendon Dysfunction and Tarsal tunnel syndrome, Foot Ankle Int 2002 Mar;23(3):212-20

- Alshami A, Babri A, Souvlis T, Coppieters M. Biomechanical Evaluation of Two Clinical Tests for Plantar Heel Pain: the Dorsiflexion-Eversion Test for Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome and the Windlass Test for Plantar Fasciitis. Foot & Ankle Intern. 2007;28(4):499–505.

- Kinoshita M, Okuda R, Monkawa J: A New Test for TTS. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2002: Sept;04-A(9):1714-5

- Hudes K. Conservative Management of a Case of Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome, J Can Chiro Assoc. 2010 June 54(2): 100-106