MRI Appearance of Rotator Cuff Tears

MRI Appearance of Rotator Cuff Tears

The assessment of the rotator cuff tendon is one of the most common reasons for MR imaging of the shoulder. Most frequently, the study is ordered to rule out rotator cuff tears. If a tear is present, it is important to define the type of tear and quantify any defects. This information may be useful in determining if conservative care is warranted, or surgery is indicated.

Tears come in a variety of types. The simplest and most easily interpreted is the complete, full-thickness rotator cuff tear. Many cuff tears are not full thickness, however, so let’s begin by defining the types of tears.

Full-Thickness Tear

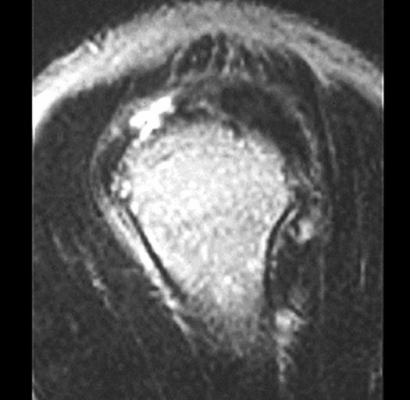

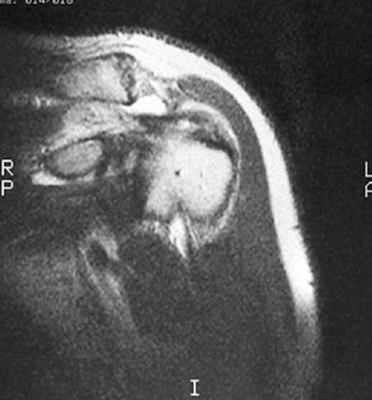

A full-thickness tear extends completely from the bursal surface of the tendon to the articular surface (1). These tears manifest high signal intensity on the T2 weighted and STIR sequences. The size of the tear should be indicated on the report and include the AP and transverse dimensions. The coronal images allow measurement in the transverse dimension (fig. 1), while the sagittal images allow measurement of the tear in the AP dimension (fig. 2). If the tear extends completely from the anterior aspect of the tendon to the posterior aspect, then it is also termed a complete full-thickness tear. A tear does not necessarily have to extend that far in the AP dimension, however, and the AP measurement is useful in determining how much of the intact tendon remains. Large full-thickness tears typically also feature a degree of medial retraction of the musculotendinous junction. A large gap in the tendon with marked retraction may be more difficult to repair surgically.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Partial Tears

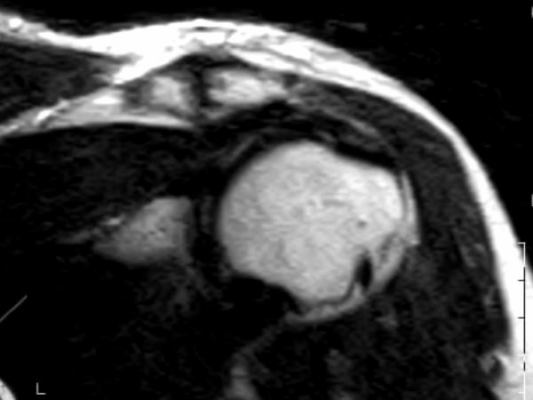

Partial tears are defects that do not extend completely from the bursal to the articular surface (superior/inferior tendon surfaces). A tear may originate from either the bursal or articular surface and extend to a varying degree through the tendon (fig. 3). If a tear extends through more than 50% of the tendon thickness, then surgery is a viable alternative. If the tear involves less than 50% if the tendon thickness, conservative care is indicated. For these reasons, the percentage of tendon involvement needs to be assessed.

Figure 3

Figure 4

Partial tears do not always extend from the surface of the tendon. Some tears are purely intratendinous. Neither the bursal or articular surface of the tendon is violated in this type of tear (fig. 4). These tears also exhibit increased signal intensity on the T2 and STIR weighted sequences and may involve varying volumes of the tendon substance. MRI is of particular benefit in the diagnosis of these types of tears, as arthroscopy will not show them. Because arthroscopy visualizes only the outside surface of the tendon, the pathology that is wholly intratendinous will not be obvious. There is a gradation of T2 signal intensity from tendinosis to intrasubstance tear. You may recall from the previous article on tendinosis that there may be minor increased signal intensity within the tendon on T2 weighted images with tendinosis. This signal will become gradually brighter as more fibers are damaged and the tendinosis progresses to a tear. This is not intended to give the impression that tendinosis will inevitably progress to a tear, but rather refers to a progression of signal intensity when imaging tendons from mild tendinosis to severe tendinosis to a partial tear.

This article has referred mainly to tears involving the supraspinatus component of the rotator cuff tendon, as it is the most commonly involved tendon. The findings that have been discussed are directly transferrable to the infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis tendons as well.

Joint Fluid

There are often associated findings with rotator cuff tears. Often joint fluid will track into the tendon sheath of the long head of the biceps with a full-thickness tear. This should not be mistaken for biceps tenosynovitis.

The suprahumeral space is often decreased with rotator cuff tears. This is the space between the superior aspect of the humeral head and the inferior surface of the acromion. If this space is less than 7.0 mm, space is deemed to be abnormal. This finding may actually be seen on plain film radiography and can be a secondary indicator or rotator cuff tendinopathy. This finding may support the decision to obtain an MRI examination to assess for cuff tear.

Conclusion

As mentioned at the start of this series, shoulder pain can be a confusing symptom. Accurate identification of rotator cuff pathology may be of paramount importance when formulating a treatment regimen for a patient with shoulder pain. MRI remains the best diagnostic imaging tool for this purpose.

1. Stoller D. W.: Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine, ed 2. Philadelphia, J. B. Lippincott Company 1993.