Hip Stress Fracture

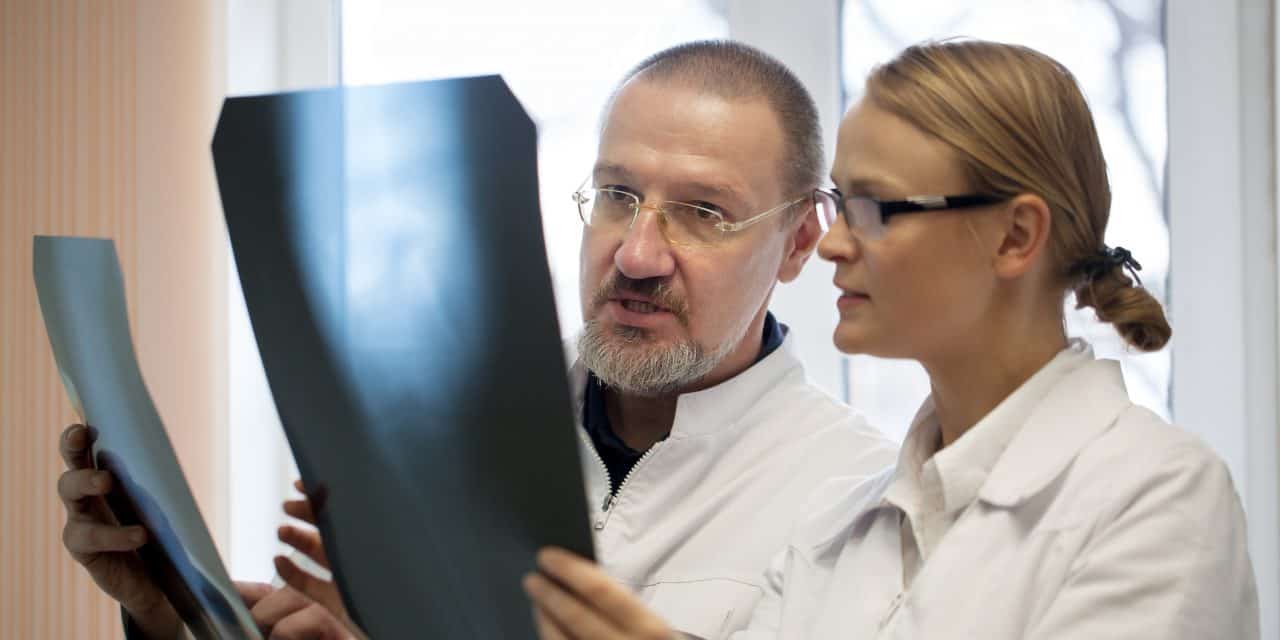

I find stress fractures to be a very interesting topic in radiology. Partly this is due to the fact that early on in the evolution of a stress fracture, it may be completely invisible on plain film x-ray and yet produce considerable symptomatology clinically. The promoting of increased physical activity seems to be ubiquitous in American society today. Although the advice is frequently ignored by large segments of the population, in other instances the individual can take it to problematic extremes when physical activity is overdone. For instance, runners may be extremely avid, and it can be difficult to convince a runner to alter his or her training schedule to decrease the stress on a given lower extremity bone.

Stress Fractures

Stress fractures exist in two forms, both of which result from repetitive stress of a lower magnitude than that required to produce an acute traumatic fracture. These would be categorized as either fatigue or insufficiency fractures. The type that we are covering today relates to the fatigue type of stress fracture. This fracture results from abnormal activity on normal bone. Over time this increased stress on the bone may result in the development of a fracture.

In the hip, this can be extremely problematic. It can be very difficult to remove stress from the hips, given the fact that as human beings we depend on normal ambulatory function so heavily in our daily lives. A stress fracture in the hip may be precipitated by a prolonged activity, such as long-distance running, dancing or sports that require extensive running. Particularly when there is an increase in the degree of intensity or changes in footwear, the stress may become overwhelming. This may be exacerbated by muscular imbalances on skeletal structures or altered biomechanics, such as foot deformities or leg length inequality.

Microfractures

Microscopically there may be the development of microfractures in the bone, which can form a small hairline fissure. The pain may develop slowly over time and is often described as a deep, dull aching sensation (particularly during activity) that initially disappears with rest. If the symptoms are left untreated, they often worsen and may permanently impair an athlete.

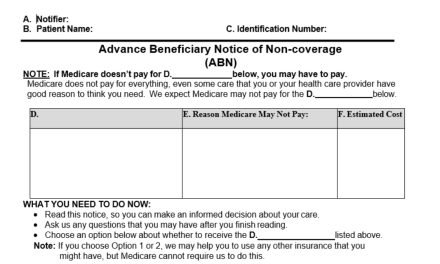

Initially, the x-ray may appear normal. There may be a latent period between 10 and 21 days before a radiographic sign becomes evident (1). A first radiographic appearance may consist of a line of increased density. The margins of this finding may be hazy and ill-defined (Fig. 1). Figure 1 demonstrates this finding along the medial neck of the femur that extends obliquely to the lateral cortex. Over time this may progress to a radiolucent line (Fig. 2). This line may not extend through the full length of the bone.

Figure 1

Figure 2

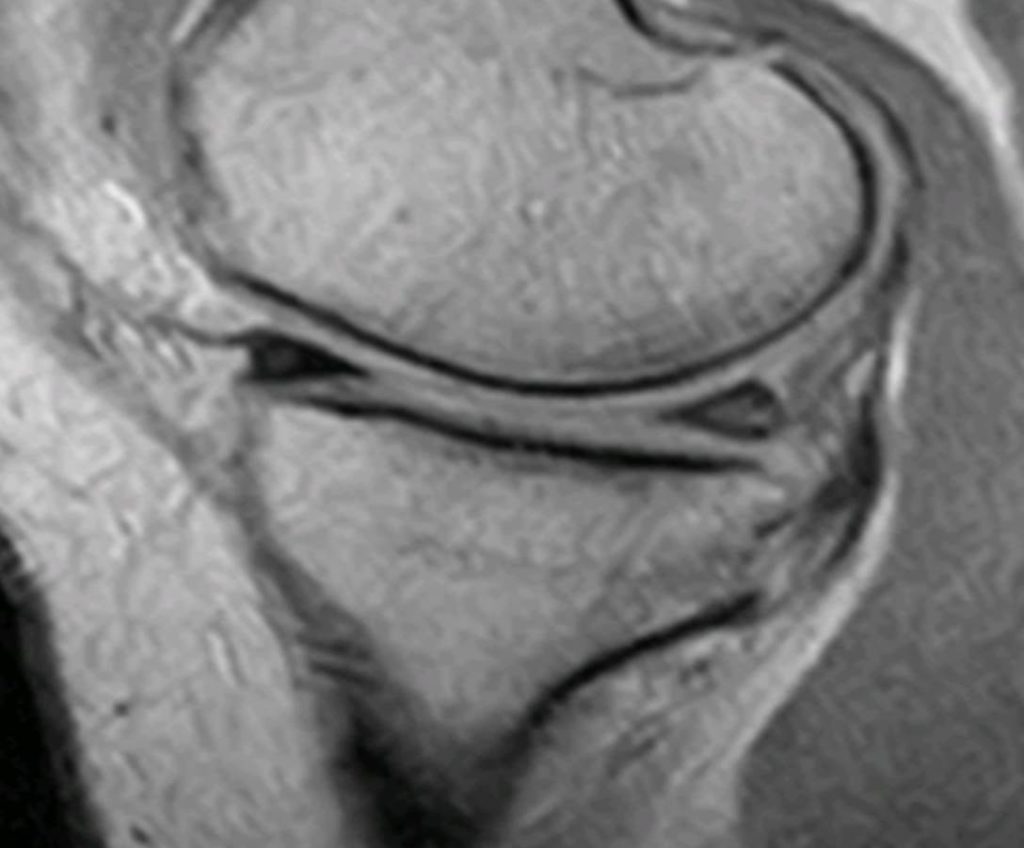

Figure 3 demonstrates a fracture line that extends from the superior aspect of the femoral neck inferiorly to the midpoint of the neck. With MRI it is possible to identify findings early on in the fracture evolution, due to MRI’s sensitivity to edema in the bone. This edema manifests as dark low signal intensity on the T-1 weighted images (Fig. 4) and bright high signal on the T-2 or STIR images (Fig. 5). Figure 5 demonstrates a high signal band surrounding a low signal intensity fracture line.

Figrue 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

If the symptoms do not cause an individual to alter his or her activity to lessen the stress on the hip, the results may be profound. A full-blown, complete fracture of the hip may occur. Generally, surgical intervention is not required for a stress fracture; however, if it does progress to a complete fracture, it may require surgical stabilization (Fig 6).

Conclusion

If clinically you suspect that a stress fracture may be developing, but the plain film x-ray is normal, you should order an MRI examination. The MRI will show change earlier than x-ray. Another option would be to do a radionuclide bone scan. A CT exam may be beneficial in demonstrating the margins of a stress fracture; however, it will not show early change. MRI is the preferred imaging modality for detecting stress fractures in the pre-radiographic stages. Contrast imaging is not required.

References

1. Yochum T.R., Rowe L.J.: Essentials of Skeletal Radiology, ed 3. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005