Diagnosis Based Clinical Decisions

As reported in JAMA Internal Medicine, back pain care is actually worsening. I truly believe that chiropractic physicians are poised to reverse this trend. Chiropractic physicians have the knowledge and resources to address the complicated world of back pain. In the last issue of the ICS Journal, I presented a cohort study in which clinical prediction rules were used for patients with lumbar radiculopathy secondary to a herniated disc. To follow up that article, I felt it would be important to actually present the clinical decision rule on which that article was based.

The first portion of this Diagnosis Based Clinical Decision Rule (DBCDR)is to answer the “three essential questions of diagnosis.” The authors suggest that these questions provide the most clinically relevant information for determining the patient’s diagnosis and best management strategy. The questions are:

- Are the patient’s symptoms reflective of a visceral disorder or a serious or potentially life-threatening illness? – Cancer, benign tumors, cauda equine syndrome, myelopathy, seronegative spondyloarthropathies, fractures, infection, etc.

- From where is the patient’s pain arising? – Determination of the affected tissue is not enough, but the characteristics of the patient’s pain are essential determining the most appropriate management strategy. The authors propose the 4 signs of greatest importance are: centralization, segmental pain provocation, neurodynamic signs, and muscle palpation signs.

- What has gone wrong with this person as a whole that would cause the pain experience to develop and persist? – The clinician’s attempt should be to determine if there are any other factors than the pain generating tissue that serve to maintain or perpetuate the pain experience. Is there a presence of dynamic instability, central pain hypersensitivity, oculomotor dysfunction, fear avoidance, passive coping or depression?

Formulation of your management strategy:

The authors are quick to point out that the use of the DBCDR is not a classification, nor is it a traditional diagnosis. What the DBCDR is a collection of sign(s) from which the clinician can make treatment decisions. It effectively serves as a working hypothesis which is tested through treatment.

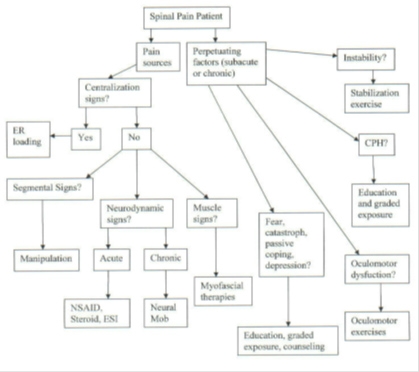

One of the important factors of the DBCDR is that pain generators and perpetuating factors interact in producing the clinical picture we see in everyday practice; therefore, both must be addressed. The management algorithm is as follows:

Management strategies in response to question 1:

Any significant findings that are suggestive of visceral referral need to be properly evaluated with diagnostic testing and/or referral.

Management strategies in response to question 2:

Centralization: If the patient centralizes, the treatment of choice is end-range loading exercises in the direction which abolishes/centralizes the patient’s symptoms (McKenzie Therapy). Because centralization signs can be addressed with exercises and self-care strategies, these signs are addressed first. The authors also suggest the use of distraction manipulation.

Segmental Pain Provocation Signs: The authors suggest that for patients with segmental pain provocation signs as well as centralization signs, end range loading maneuvers be utilized first, with no action being taken on the segmental pain provocation signs until end range loading has been fully explored. In patients with segmental pain provocation signs in the absence of centralization signs, spinal manipulation is the recommended therapy.

Neurodynamic Signs: Due to the chemical nature of radicular pain in the acute setting, anti-inflammatory intervention is suggested. This can be in the form of NSAIDs, oral steroids or epidural steroid injections. In patients with chronic neurodynamic signs, many patients may demonstrate centralization signs when end range loading strategies are applied. In the absence of centralization or in patients with residual radiculopathy, neural mobilization which attempts to mobilize the involved nerve root to improve mechanics and decrease sensitivity is suggested. The authors also point out that distraction manipulation is also used for lumbar radiculopathy.

Muscle Palpation Signs: The authors suggest many different forms of treatment including ischemic compression, muscle lengthening techniques to trigger point injections.

Management Strategies in Response to Question 3:

Dynamic Instability: The authors suggest exercises in which motor control of the spine is improved in which no specific technique or exercise is given.

Central Pain Hypersensitivity (CPH): The key is to identify the source of the increased nociceptive input and gradually try to desensitize the area. It may be appropriate to use a graded exposure-response.

Oculomotor Dysfunction: Treated with exercises designed to train eye-head-neck movements.

Fear, Catastrophizing, Passive Coping and Depression: The authors report that prior studies suggest there is an association between fear and catastrophizing with CPH. The authors suggest that the appropriate treatment choice would be to educate the patient about the presence and nature of CPH. This education must be followed by a graded exposure.

Diagnosis Based Clinical Decision Rules provide a real world, predictable model that each of us can implement into our clinics that will help us recognize the best treatment approach for these patients. For those who are interested, the authors also discuss “classification” systems implemented to assist in the treatment of back pain, and how those systems differ from DBCDR.

The ICS has an amazing initiative to increase the number of Illinois chiropractic patients to 18% of the population by 2018. If we implement Diagnosis Based Clinical Decision Rules, such as the one discussed in this article, we will not have any problem getting to that number.

- Murphy DR, Hurwitz EL. A theoretical model for the development of a diagnosis-based clinical decision rule for the management of patients with spinal pain. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2008;8:75.

- Mafi JN, McCarthy EP, Davis RB, Landon BE. Worsening trends in the management and treatment of back pain. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(17);1563-1581.