A Simple Question – “What Happens When the Pain is Gone?”

Patients ask this question periodically. The simple answer is that you want to keep the pain gone, right? How best to do that is a matter of debate.

Some of the strategies below seem simple, but in practice are difficult to execute. The best case scenario is that the patient and health care provider execute these strategies together after the pain is gone. Executing a specific plan tailored toward the patient’s goals helps drive down the chance of recurrence. Reducing recurrence avoids unnecessary medical costs. Unnecessary medical procedures cost our health care system over $210 billion annually. (1) Over $765 billion in medical expenditures are wasted annually. (2)

Several strategies to keep the pain gone are outlined below:

1. Complete A Comprehensive, Thorough Rehab Program That Reduces Compensation Patterns

It is well known that incomplete rehab is a risk factor for re-injury or secondary injury. (3, 20) Secondary injury is an injury to a separate, but related, body area. Patients can form compensation patterns of movement that occur despite significant pain reduction and functional improvement. The body learns to adapt and, therefore, “cheat.”

Compensations can aggravate the initial problem or cause secondary issues. An example of compensation occurs when gluteal muscle strength changes following an ankle sprain. (4) Fast forward months down the road, and it is possible that the lack of gluteal strength leads to other problems, such as decreased athletic performance or increased chances of the ankle, knee, hip, low back or other kinetic chain injuries. Remind your patients to follow your advice and stick with the indicated treatment plan to result in the best chance of reducing compensations, re-injuries or secondary injuries.

2. Focus on General Health

Doctors are seeing increased rates of chronic disease, such metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, autoimmune diseases, fatty liver, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, high levels of triglycerides, heart disease and cancer. Combine these chronic diseases with a culture that includes eating inflammatory foods, exposure to high levels of stress, and insufficient sleep and exercise, and we are setting the table for never resolving simple MSK (musculoskeletal) injuries. The conditions above all impact healing cells. Therefore, back pain, shoulder pain or knee pain may not “heal” to the level it should.

It is a good strategy to give patients some good general health tips on topics such as nutrition, hydration, weight loss, stress reduction, sleep, and exercise. Tell your patients it is most effective to improve health with small, daily changes to lifestyle habits that can stand the test of time.

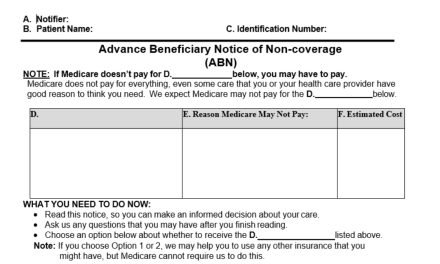

3. Tell Patients to Consider a Comprehensive Review of Their Medications

Many Americans are over-medicated. (5, 6, 7) The rate of over-medication is staggering in the U.S. when compared to other industrialized countries.

Medications can be prescribed:

- without clear clinical benefits

- for symptoms rather than diagnoses

- with overlapping clinical benefits

- with overlapping side effects

- without doses adjusted to a patient’s current health status.

As Illinois licensed chiropractic physicians, it is within our scope to make recommendations concerning non-prescription products. Although we know it is not in scope to recommend that a patient take or cease taking a prescription medication, we can provide general information and a recommendation that the patient sees the prescriber to evaluate the effects of prescription drugs.

All treatments come with some risk, and medication is no exception. Ideally, there should be clear and favorable benefits with minimized risks. Once a patient’s pain is gone, a review of medications is warranted. Patients should be advised when appropriate to contact the prescribing physician or primary care physician for a comprehensive review.

Common Medications

The most common medications in the MSK (musculoskeletal) realm are pain medications (opioids), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and muscle relaxers. Each of these types of medications have benefits and risks.

Opioids come with the risk of poor outcome and addiction. NSAIDs can affect soft tissue healing, as well as increase the risk for stroke, heart disease, heart attack, and ulcers. Steroids may spike blood sugar, cause weight gain and affect the body’s immune system. Muscle relaxers can cause drowsiness, which creates risk for persons operating motor vehicles or performing tasks that require memory, concentration or awareness. This is just a sample of the most common side effects from the most commonly prescribed medications for MSK conditions.

We should also be aware that many of our patients are on cholesterol medications, blood pressure medications, anti-anxiety medications, anti-depressant medications, anti-seizure medications, immune-suppressing medications (autoimmune disease) or anti-coagulant medications (blood thinners). All these medications come with complications that can impact the outcome of many of the MSK (musculoskeletal) diseases that we treat. Patients should be encouraged to check with their prescribing physician, physician’s office or a pharmacist about benefits vs. risks of prescribed medication(s) after the pain is gone.

4. Check out the Healing Environment

We are finding more and more that a patient’s “healing environment” is not purely limited to tissues physically healing. The psychological environment plays a huge and underappreciated role in resolving injuries. This is particularly apparent in injured workers returning to their occupations. (8, 9, 10) Patients’ social interactions with their families, friends, colleagues, co-workers and medical providers all matter.

Recent studies indicate that what doctors say to patients and how they say it to patients can facilitate or impede the healing process. An ill-timed or misplaced suggestion by a health care provider can set the patient back quite a bit. (11) Healthcare providers must be honest, approachable and stay positive. Patients feed off that.

5. Social Re-Integration

Patients may have trouble re-integrating back to their environment following the resolution of pain. If you’ve ever worked in athletics, you realize there is a psychology component associated with rehabbing athletes. Athletes are often scared to perform their sports because of fear of re-injury. Fear can be a big obstacle!

While fear of re-injury is acknowledged in the sports realm, it is also a major obstacle to average Joe/Jane reintegrating back into their social environments. One example is a recreational athlete like a runner who feels the effects of social withdrawal, such as depression, anxiety, angst or nervousness, when rehabbing. Later when making the transition from pain (injury) to performance (running/racing), the runner may still be fearful.

Another example is the elderly nursing home patient who fell months ago. The elderly patient is now scared to balance for any length of time without the use of a walker, cane or a helper. Our last example is the 45-year old woman that sprained an ankle in the yard. She has become increasingly sedentary as a result. She no longer goes for her morning walks with her friends for fear that she could re-injure the ankle. These are just a few examples.

Reintegration

Re-integration back into the patient’s normal, daily environment is not often discussed during treatment. Unintended consequences like fear, anxiety, stress, social isolation can develop, serving as obstacles in the rehab process. MSK providers need to do a better job of addressing this obstacle. After the pain is gone, consider guiding your patients through this process with a positive attitude and graded exposure.

Graded exposure means exposing patients in small doses back to pre-injury activity levels. “Slow cook” this, like good barbecue if necessary (“low and slow”)! Develop and implement a specific plan that slowly reintegrates the patient back into this or her pre-injury life and pre-injury activities. Gradual reintroduction of feared activities assists doctors and patients in obtaining the desired, outstanding outcome.

6. Build Up Your Patient’s “Emergency Fund” by Building Adaptability, Resiliency and Capacity

A patient’s physical emergency fund is analogous to a financial emergency fund. A financial emergency fund is the sum of money you keep around so that when bad things happen in life, you’ve got something to cover unexpected expenses. The financial emergency fund fixes a broken car, patches a leaky roof, replaces a washer or dryer that’s gone bad, etc. The physical emergency fund for a patient’s body is a reserve of strength, stamina, mobility, stability, endurance, mental fortitude, and confidence. A targeted strength and conditioning program is the tool by which to build up a patient’s physical emergency fund.

Conditioning Program

This can be a fun exercise. This is where human performance meets injury rehab. Performance measures are specific to the patient’s demands. Everyone from everyday Joe/Jane to weekend warriors to elite athletes must achieve an individual level of performance as they make their way through life.

Everyday Joe/Jane picks up a child from the ground (deadlifting), takes out the trash (sled pulls, farmer’s carry or suitcase carry), puts objects on the shelf (overhead press), takes objects off a shelf (overhead pulls), sits down and gets up from a toilet seat (“potty squats”). The average person needs the capability of performing daily routine tasks efficiently to sustain a certain quality of life.

Athletes need to train the requirements of their sport. Does the athlete need short, powerful bursts? Does the athlete compete over a prolonged length of time (endurance)? What are the athlete’s shortfalls? Is it strength, symmetry, quickness, flexibility, mobility, stability, balance, coordination, lateral agility, recurring injury, etc.?

Everyday rehab typically never focuses on building a reserve of adaptability, resiliency or capacity. Inadequate rehab occurs in both everyday Joe/Jane and in elite athletes. Everyday Joe/Jane will stop treatment once the pain is gone. Athletes are likewise rushed back onto the playing field before adaptability, resiliency and capacity are restored. Building adaptability, resiliency and capacity are building your patient’s “emergency fund.”

Conclusion

Exercise is not just the emergency fund for the MSK system. (12, 13) Exercise deposits into the fund for the cardio-respiratory system (heart & lungs), nervous system (brain, spinal cord, peripheral nerves), gastrointestinal-digestive system (stomach & intestines), genitourinary (GU) system (kidneys, bladder, ureters, urethra), vascular system (blood vessels), immune system, integumentary-exocrine system (skin and glands), endocrine-metabolic system (thyroid gland, pituitary gland, adrenal glands, pancreas, ovaries, testes, etc.) and reproductive system. Exercise gives towards your patient’s emergency fund. Sedentarism (sedentary lifestyle) takes away from that fund.

We want our patients to have a robust fund. We want that fund to provide for them when the demand is necessary. We want that fund to insulate them against abnormal stresses. We want the fund to protect them from injury and sickness. We want to make them leaner, bigger, faster, stronger, more confident and basically “harder to kill.” As chiropractic physicians, we can implement this strategy of building adaptability, resiliency, and capability for our patients once the pain is gone.

References

1. https://newsatjama.jama.com/2017/09/27/jama-forum-the-high-costs-of-unnecessary-care/

3. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6874174

4. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1421486/

6. http://www.businessinsider.com/infographic-america-is-over-medicated-2012-2

7. https://www.globalresearch.ca/pill-nation-are-americans-over-medicated/5367349

8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4979741/

9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5444584/

10. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3671916/

11. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25811262

12. https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/pa-health/index.htm

13. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1402378/

14. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4331171/

15. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8680943

16. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6874174

17. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11394599

18. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2095254612000452

19. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jpfsm/3/1/3_139/_pdf

21. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22724435

*** Disclaimer:

The views and opinions above represent that of the author, Dr. Dino Pappas. They do not reflect the official policy or position of any agency or company that Dr. Dino Pappas may have a relationship or affiliation with. ***