Upper Crossed Syndrome

The face of healthcare reimbursement is changing rapidly. Providers are now rewarded for timely outcomes and penalized for prolonged treatment plans. Identifying factors that may slow your patient’s recovery is crucial. This article will show you how to identify and treat one of the most common contributors to ongoing upper body complaints: Upper Crossed Syndrome.

“Upper Crossed Syndrome,” also known as “Cervical Crossed Syndrome,” was first described by Vladimir Janda in 1979 as a predictable pattern of alternating tightness and weakness involving the neck and shoulders. (1) The condition frequently contributes to neck and back pain and is associated with diagnoses ranging from cervicogenic vertigo to rotator cuff pathology. (2)

Upper quadrant muscular dysfunction does not occur at random, but rather, in a predictable pattern of altered posture as the body attempts to reach homeostasis. (3-5) The process typically begins when a muscle or muscle group is overused in a certain direction and becomes shorter and tighter (adaptive shortening). The antagonist muscles opposing this action are subject to prolonged stretch and tend to become longer and weaker (stretch weakness). (6)

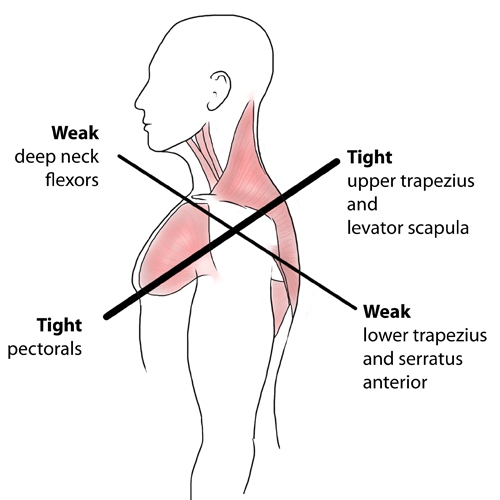

Janda classified muscles as either “postural” or “phasic.” Upper quadrant “postural” muscles (including the upper trapezius, levator, SCM, and pec major) are predisposed to tightness, while “phasic” muscles (including the rhomboid, serratus anterior, scalenes, and middle & lower trapezius) respond to dysfunction by becoming weaker. (1,4,7) The term “upper crossed syndrome” was coined because a line drawn to connect the tight muscles forms a cross with a second line drawn between the weak muscles. (8) (See figure below.)

Upper crossed syndrome is a direct result of “flexor-dominated” postures (i.e. forward use of the arms and head). This process begins in the classroom as a child and progresses with age throughout the working years. (9) Most occupations, from computer operator to manual labor, are “flexor-dominated.” (10) Workstation users are particularly predisposed from prolonged static flexor dominated postures. (9,11) Sedentary lifestyles may contribute to the problem. (9) Non-mechanical factors like low self-esteem or depression may trigger upper crossed postures. (12)

Muscular balance is required for normal function, and muscular imbalance leads to dysfunctional and inappropriate movement patterns. (13) This has a direct impact on joint surfaces and often leads to a self-perpetuating cycle of recurrent joint dysfunction. (i.e. subluxation) (4,14-16) Longstanding postural dysfunction may cause joint degeneration (1,4,17) and changes in CNS motor control. (4,16)

Poor posture can negatively affect proprioception, balance, gait, and functional performance. (17) Poor posture has been associated with increased mortality rates in older adults. (17) Upper crossed syndrome places excessive stress on the upper thoracic region and has been linked to T4 syndrome – a cause of chest pain and pseudo angina. (8)

Upper crossed patients often complain of neck pain, interscapular pain, and headaches. (2) The condition is thought to contribute to many upper body diagnoses, including cervical and thoracic intersegmental joint dysfunction, sprain/strain, discogenic pain, degeneration, vertigo, rotator cuff syndrome, thoracic outlet syndrome, costovertebral dysfunction, and TMD.

Traditional “structural” diagnoses focus on a “tissue” source for the patient’s symptoms (i.e. facet capsule, supraspinatus tendon, etc). Upper crossed syndrome is a “functional” diagnosis that requires identification of the underlying factors that contribute to structural lesions.

Assessment for upper crossed syndrome begins with visual inspection. The ideal standing posture, when viewed from the side, is a plumb line passing through the ear, shoulder, greater trochanter, and slightly anterior to the lateral malleoli. (19,20) Postural evaluation of patients with upper crossed syndrome will reveal a forward head posture with upper cervical extension, elevated and protracted shoulders, scapular winging, and a thoracic hyperkyphosis. (8)

Hypertonicity will be found in the upper trapezius, levator, pec major, and SCM. Palpation will often demonstrate tenderness or trigger point activity in the aforementioned muscles as well as the concurrently weak rhomboids, serratus anterior, middle & lower traps, scalenes and deep neck flexors.

Functional assessment of neck flexion can be performed with a “Neck flexion test.” The test is performed when a patient in the supine position is asked to lift his head several inches off of a table to look at the toes. The normal firing pattern for neck flexion is the longus capitus, longus coli, SCM, and finally, anterior scalenes. The clinician observes for a “normal” movement pattern, which would be initiated with a chin tuck and smooth reversal of the cervical lordosis. An “abnormal” screen would result in the chin moving forward into protraction from overcompensation by the SCM. Abnormal neck movement suggests weakness of the deep neck flexors.

The “Deep neck flexor endurance test” is another maneuver for assessing the deep neck flexors. This test starts with the patient in a supine, hook-lying position. The patient performs chin retraction, then lifts the head an inch off of the table. The clinician places their flat hand on the table below the patient’s occiput. If the patient’s head begins to lower or their anterior neck skin folds separate, the patient is reminded to “tuck your chin and hold your head up.” The test is timed until the patient’s head touches the clinician’s hand for more than one second. The average endurance for men is about 40 seconds and 30 seconds for women. Those with neck pain average closer to 20 seconds. Low endurance suggests neck flexor weakness with a predisposition to over utilize the SCM, platysma, and hyoid- resulting in an upper crossed posture and neck pain. (21,22)

Patients with upper crossed syndrome will often demonstrate abnormal shoulder abduction. The normal sequence for shoulder abduction is progressive firing of the supraspinatus, deltoid, infraspinatus, middle and lower trapezius, and contralateral quadratus lumborum. Patients with upper crossed syndrome frequently demonstrate early shoulder elevation (prior to 60 degrees of abduction) due to overactivity of the upper trapezius and levator scapula. (23,24)

Patients with upper crossed syndrome often have weak scapular stabilizers (serratus anterior). Scapular stability may be assessed by the Quadruped rock test (aka Push up test). This assessment is performed by having the patient assume a quadruped position and slowly rock forward and backward while the clinician observes for signs of scapular winging.

Joint dysfunction may arise secondary to muscular imbalance. (4,14-16) Janda noted that upper crossed syndrome creates a predictable pattern of joint dysfunction involving the atlanto-occipital joint, C4-5, C7-T1, T4-5, and the glenohumeral joint. (8,25,32)

Management of upper crossed syndrome should first attempt to eliminate abnormal proprioceptive input through joint mobilization and myofascial release. (B) Rehab then progresses sequentially through stretching, strengthening, and finally, fascilitation of normal movement patterns. (4)

Sherrington’s law of reciprocal inhibition states that when one muscle is hypertonic, its antagonist relaxes. (26,27) This law necessitates that hypertonic muscles be lengthened before embarking on the process of strength training. Stretching and myofascial release should be directed at the pectoral muscles, SCM, upper trapezius, and levator. Additionally, release of myofascial adhesions may be necessary in the rhomboids, serratus anterior, middle and lower traps, and scalenes. Manipulation may be necessary for restrictions in the cervical, thoracic, and shoulder regions. (32)

Strengthening exercises should focus on the rhomboids, serratus anterior, middle & lower trapezius, and scalenes. Functional rehabilitation must include proprioception and exercises to “groove new movement patterns.” (28) Specific rehab exercises would include chin retraction, Brugger’s position, and scapular stabilization. (29-31) Patients should be counseled to reduce repetitive stress, including ergonomic workstation modification.

References

- Page P., Frank C.C., Lardner R., Assessment and treatment of muscle imbalance: The Janda Approach 2010, Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics

- Hertling D & Kessler R. Management of Common Musculoskeletal Disorders: Physical Therapy Principles and Methods. Fourth Edition. Lippincot Williams & Wilkins. 2006;150.

- Tunnell, P. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 1996;1(1), 21.

- Janda, V., 1987. Muscles and motor control in low back pain: assessment and management. In: Twomey, L.T. (Ed.), Physical

- Therapy of the Low Back. Churchill Livingstone, New York, pp. 253–278.

- Janda Syndromes. www.jandaapproach.com accessed 8/19.2014

- Kendall F, McCreary E, Et. al. Muscles. Testing and Function with Posture and Pain. Baltimore MD: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins. 2005;5th ed

- Moore, MK. Upper Crossed Syndrome And Its Relationship To Cervicogenic Headache. JMPT July/Aug. 2004;27,6:416.

- Janda compendium. Vol II. Minneapolis: O.P.T.P., p. 7-13

- Thacker, D, Jameson J, Baker J, Divine J, Unfried A. Management Of Upper Cross Syndrome Through The Use Of Active Release Technique And Prescribed Exercises. Logan College Senior Research Paper

- Key, J., Clift, A., Condie, F., Et.al. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 2008;12,113.

- Yoo, W., Yi, C., Kim, M. Effects of a ball-backrest chair on the muscles associated with upper crossed syndrome when working at a VDT. Work 2007;29:239

- Christensen, K. Manual muscle testing and postural imbalance. Dynamic Chiropractic 2000;15:2.

- Liebenson C. Rehabilitation of the Spine: A Practitioner’s Manual. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1996; 97–112,196

- Lewit K. The functional approach. J Orthopedic Medicine 1994; 15:73–74.

- Key, J., Clift, A., Condie, F., Et.al. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 2008;12,113.

- Tunnell, P. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 1996;1(1), 21

- Page, P. Muscle imbalances in older adults: improving posture and decreasing pain. The Journal on Active Aging. 2005;3:30

- Murphy DR. Conservative management of cervical spine syndromes. McGraw Hill Company, Inc, 2000. p. 107-12.

- Lewit K. Manipulative therapy in the rehabilitation of the locomotor system. 2nd ed. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1991. p. 79-80

- Domenech MA, Sizer PS, Dedrick GS, McGalliard MK, Brismee JM. “The Deep Neck Flexor Endurance Test: normative data scores in healthy adults.” PM R. 2011 Feb. Web. 08/18/2012.

- Harris KD, Heer DM, Roy TC, Santos DM, Whitman JM, Wainner RS. “Reliability of a measurement of neck flexor muscle endurance.” Physical Therapy 2005 Dec. Web. 08/18/2012.

- Janda V. Muscle Function Testing. London: Butterworth, 1983.

- Chapman-Smith D. The Chiropractic Report. Rehabilitation and Chiropractic Practice, Toronto, July 1996:4.

- www.jandaapproach.com accessed August 2012

- Hertling D & Kessler R. Management of Common Musculoskeletal Disorders: Physical Therapy Principles and Methods. Fourth Edition. Lippincot Williams & Wilkins. 2006;150.

- Page P & Frank C. The Janda Approach to Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain.www.jblearning.com/samples/0763732524/The%20Janda%20Approach.doc Accessed 7/20/14

- Phil Page Sensorimotor training: A ‘‘global’’ approach for balance training Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies (2006) 10, 77–84

- Liebenson C. Rehabilitation of the Spine: A Practitioner’s Manual. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1996; 97–112,196.

- Skaggs CD. Rehabilitative Management of Orofacial Pain. Chiropractic Rehabilitation Lecture, CMCC, Toronto, 1998.

- Waerlop IF. Lecture on Whiplash, Headache and Vertigo Diagnosis, Management and Rehabilitation 1997 CMCC, Toronto.

- Muscle Imbalance Syndromes – Upper Crossed Syndrome www.muscleimbalancesyndromes.com/janda-syndromes/upper-crossed-syndrome Accessed 7/20/14