The Personal Injury Practice

Those of us that participate in treating these types of injuries, such as the litigious whiplash in general and low-speed impact-related injuries in particular, are aware that we have become part of the medicolegal arena and its experts from fields outside of chiropractic and medicine. The most common issues that these experts face relates to causation, i.e. which driver was at fault – and the forces or loads experienced by the occupants of the involved vehicles. Here are key elements of the personal injury practice.

MVC Report:

The source of data for the following was the 1990 General Estimates System/ Fatal Accident Reporting System statistics. 1.513 million (23.4%) were rear impact collisions of which 535,000 were associated with injuries. However, be cautioned that the source data are police-reported crashes and reflect only those injuries that were both reported and immediate. The current best estimate is that about 3 million new whiplash injuries occur yearly in the U.S. There are those with delayed onset of symptoms which is not accounted for and those crashes that are never reported (1).

With this in mind, upon having a new patient present to your office as a result of a motor vehicular crash (MVC) it is imperative that your office obtain the Illinois Motorist Report (IMR) that the patient (providing that they are the driver or passenger of the vehicle) acquired from the Police. Within this report, one will see the first name which indicates the person that struck the auto (bullet), while the second name indicates the person that was struck (target). Providing that your patient was struck then the logistic of the MVC as noted in the IMR will be as follows: defendant’s name (who caused the accident), plaintiffs name (your patient), Insurance information (both plaintiff and defendant’s), and mechanism of collision. In the event that your patient was involved in a multi-collision then your patient would be one of the involved vehicles.

The largest healthcare fraud that tends to involve DCs is noted in PI/MVC cases. The following represent common fraud schemes.

Common types of fraud include:

- Lying about the way a loss occurred.

- Including previously existing damage to a car when submitting a claim.

- Listing an adult as the primary driver of a car when it’s actually someone under 21.

- Numerous occupants within the same vehicle.

- Withholding information about past accidents, traffic tickets, claims, policy cancellations or non-renewals, other insurance in force, and medical and disability history.

- After being injured, agreeing with a doctor’s or lawyer’s suggestion to stay out of work for a longer time to get a higher insurance settlement.

- Staged accidents may occur when a driver deliberately stops in front of a car to cause a low-speed crash. The driver who staged the accident claims that he and his passengers suffered injuries; they seek payment from the other driver’s insurance company.

- Other cheaters report accidents that never happened.

- Another scam involves lawyer-doctor conspiracies. “Runners” prowl the streets listening to the police radio and looking for accidents. Their job: Bring victims into the fraud mill.

- Next, a lawyer takes the victim’s case while a doctor builds up medical bills, giving needless treatment or charging for treatment never given.

- Defrauders then exploit hard-to-diagnose injuries such as whiplash. Their goal: an insurance settlement much greater than actual damages.

This is where the Illinois Motorist Report is so essential in a practice. The Law Enforcement Officer will place in this report how the MVC occurred. Although s/he may not have been a witness to this crash, s/he will place what the plaintiff, defendant, and any other witness had stated. The IMR and patient presentation will at least assist the DC in making an intelligent decision on whether the MVC is a real or a sham.

Dealing with attorneys will be determined if that DC has dealt with him/her before. If this is the first time associating with that attorney, then contact should be made with other DCs in the area to determine if that attorney is one who will provide good legal help for their patients.

History:

In obtaining the history, the following is information that should be collected by the physician or an associate physician (1).

- Current employment status and status at the time of the crash. Are they different and, if so, why?

- Any disability that existed previous to the crash, or subsequent to it, including work restrictions, limitations, changes in the job description, and whether these were prescribed by a physician or were self-imposed.

- Past medical/chiropractic history, including surgeries (when and type; residuals), fractures (when, where, and how they occurred; residuals), serious illnesses and any residuals. Also ask about any present health problems (diabetes, hypertension, epilepsy, etc.).

- Inquire about prior workers’ compensation claims (when, type of injury, any awards or permanent disability, type of treatment, etc.; residuals).

- Ask about prior auto crashes or other personal injuries. Get details as to date, type of crash, the extent of the injury, type of treatment rendered, and any residuals or permanent impairment which might have resulted.

- Also ask about any other injuries to the head, neck, back, or extremities from falls, sports, etc., obtaining information about them as above.

Note: Patients may hesitate to supply information about their past, fearing that it may adversely affect their current lawsuit. This information, if omitted, is often uncovered at a later time, often with devastating results. I usually explain this to patients at the start of my consultation with them and relate an example of how a patient’s failure to disclose the facts to me had a disastrous effect on the outcome of their case. - Prior history of any of the patient’s current complaints.

- History of the injury; here we need enough detail to allow some estimation of the physical forces experienced by the patient. Ask about the following:

- Treatment history: In chronological order, you must document all of the physicians or therapists that the patient saw before you (if any).

Chief complaints:

The most efficient method is to employ the OP2QRST mnemonic where:

O = Onset: When did symptoms first appear?

P1 = Provocative: What makes symptoms increase?

P2 = Palliative: What gives relief of symptoms?

Q = Quality: Sharp, dull, aching, throbbing, burning, stinging, numb, etc.

R = Radiation: Where does the pain radiate to?

S = Severity: I use a Visual Analog Scale of 0 to 10, where 10 is considered the most extreme.

T = Temporal: When does the patient have the pain? How many days out of the week? How much of each day? Where: 10% = rare; 25% = occasional; 50% = intermittent; 75% = frequent; 100% = constant

I found that it was easier for patients to place numbers in defining their pain. I have the patient describe their complaints, one area at a time, beginning with the most bothersome.

Most practitioners record a surprisingly scant history regarding their patient’s type of injury and complaints. However, because much of our understanding of the nature and extent of the soft tissue injury is based on a broad range of data, which includes special tests, the history of symptoms, the physical examination, and knowledge of the forces involved in the crash, it seems only reasonable that we should record as much information as possible so as to provide a firm basis for our opinions and impressions (1).

It is a good idea to observe your patient for signs of pain or dysfunction. How does s/he sit? How is his/her gait? Is his/her posture normal or antalgic? During the course of the examination have him/her remove his shoes and socks. Can s/he do it effortlessly? Make note also of your patient’s appearance and attitude. Are they consistent with the complaints given? (1)

Examination:

The following neurological examination should be considered and is usually performed in cases of MVC trauma:

- Cranial nerves

- Grades of muscle strength:

- Sensory exam

- Proprioception

- Coordination

- Deep tendon reflexes (DTRs)

- Pathological and superficial reflexes

Note: When history or patient’s presentation suggests the possibility of fracture or dislocation, even when remote, radiographs should be taken prior to orthopedic or ROM testing.

Continue with your examination to include and recorded:

- Musculoskeletal

- Muscle spasm; Muscle tone; Trigger points and their reference zones.

- Palpation

- Range of Motion

- Active and/or passive

- Indicate the method of measuring and recording

- Visual, goniometric, or dual inclinometer.

- Mensurations

- Indicate whether in centimeters (cm.) or inches (in.)

- Orthopedic Testing

- An excellent reference for orthopedic and neurological tests and signs is Ron Evans’ textbook, Illustrated Essential Orthopaedic Physical

Assessment (3)).

- An excellent reference for orthopedic and neurological tests and signs is Ron Evans’ textbook, Illustrated Essential Orthopaedic Physical

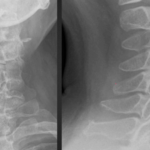

Radiological Indications

In cases of MVC trauma, plain films of the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spines are indicated when warranted by pain. Remember that many types of trauma are missed on hospital radiographs. Don’t rely on the patient’s assurance that the films taken in the ER were “normal.” (1)

A more careful review of the literature does suggest that fractures and other pathology are not uncommon results of Cervical Acceleration/Deceleration (CAD) trauma (4) and that these are frequently overlooked on plain film examinations. In many cases, patients with cervical spine fractures have surprisingly minimal pain; in some cases, the pain is masked by other injuries (5). Also, the importance of stress views (i.e., flexion and extension laterals) has been previously reported, including a study published in the journal Skeletal Radiology (6), in which the authors concluded that “Flexion and extension films are essential to help define whiplash and other ligamentous injuries of the cervical spine.” (1)

Outcome Assesments:

Tools of documentation that are becoming an expected “standard” of proving the effectiveness of care over time, and because tracking outcomes is a means by which insurers decide in the care provided has been necessary. (7)

There are essentially three critical steps that need to be followed when establishing an outcomes-based practice: (8)

- Know which outcome tools to implement and score the tools

- Repeat the use of the tools on re-exam and compare the scores

- Most important: make clinical decisions based on the results.

Now that you have taken the appropriate history, completed the outcomes assessment questionnaires, completed the examination, and have the taken the appropriate radiological studies, you are now ready to make a clinical decision and prepared to provide a treatment plan.

As the patient improves, so should the patient see a decrease in visit frequency. What many DCs fail to do is to perform re-evaluations with outcomes assessment tools in a timely manner. It is suggested that the patient be evaluated at least once a month. Overall, proper clinical documentation is the most essential part of a practice.

The intelligent approach was written to assist those DCs in the PI/MVC practice. Understanding this approach will only aid you further in the medicolegal world. The chiropractic physician is the specialist and expert in these musculoskeletal disorders and being prepared will assist the most important person in that practice –THE PATIENT.

References:

- Croft, Arthur C., DC, MS, MPH, Whiplash Hypertext 3.0, 2003

- State Farm Ins., State Farm.com

- Evans RC: Illustrated Essentials in Orthopaedic Physical Assessment.St. Louis, Mosby—Year Book, Inc, 1994

- Freeman MD, Sapir D, Boutselis A, Gorup J, Tuckman G, Croft AC, Centeno C, Phillips A: Whiplash injury and occult vertebral fracture: a case series of bone SPECT imaging of patients with persisting spine pain following a motor vehicle crash. Cervical Spine Research Society 29th Annual Meeting, Monterey, CA, Nov 29-Dec 1, 2001.

- Malomo AO, Shokunbi MT, Adeloye A: Evaluation of the use of plain cervical spine radiography in head injury. East African Med J 72(3):186-188, 1995

- Griffiths HJ, Olson PN, Everson LI, Winemiller M: Hyperextension strain or “whiplash” injuries to the cervical spine. Skel Radiol 24(4):263-266, 1995.

- Liebenson, Craig, DC, Yeomans, Steven, DC, Outcomes Assessment: How to Satisfy the Insurance Industry with Time-Efficient Documentation.www.chiroweb.com/archives/18/02/13/html

- Yeomans, Steven, Clinical Application of Outcomes Assessment, Stamford, CT: Appleton & Lange, 2000.