Severs Disease

Severs disease, or calcaneal apophysitis is a painful inflammation of the cartilaginous growth center at the site of insertion for the calcaneal tendon. This condition, first reported by Sever in 1912 (1), is a common cause of posterior heel pain in active adolescents.

Who is Affected?

In children and adolescents, the epiphyseal growth plate is 2-5 times weaker than in adults. This means that children are more likely to suffer epiphyseal injuries from stressors that would likely cause sprains and strains in adults (2). An apophysis is thought to be most vulnerable during periods of rapid adolescent growth. As bones lengthen rapidly, soft tissues, like the gastroc/ soleus/ Achilles, become tighter and produce excessive stress on their bony attachments. Like other traction apophysitis’, Severs’ is thought to be caused by diminished resistance to shear stress at the apophyseal growth plate. The calcaneal apophysis is subject to significant shear loads, in part due to its vertical orientation and direction of pull from the powerful gastroc/ soleus. Severs disease is the second most common type of traction apophysitis behind Osgood Schlatters.

This condition is most commonly found in athletically active populations between the ages of 8 and 14. There is a slightly higher incidence in males. Severs patients often present after beginning a new sports season. Activities requiring running and jumping including soccer, basketball, gymnastics and track & field are most closely associated with the development of Severs disease, (3,4). Symptoms are bilateral in 60% of cases. (5).

Symptoms

Patients generally present with a gradually progressive complaint of posterior heel pain, made worse with activity. In some cases, the athlete will have a noticeable “post-activity limp” in an effort to unload the affected foot. Rest often relieves the pain.

Clinical findings include pain upon palpation of the Achilles insertion and a positive “squeeze test” which involves simultaneous compression of the medial and lateral calcaneus. Mild swelling may be present, and in long-standing cases, calcaneal enlargement is possible. Resisted plantar flexion/ toe raises will often reproduce discomfort. Passive dorsiflexion may be uncomfortable.

Severs patients show two common characteristics, a) gastroc/ soleus hypertonicity and b) significantly greater weight-bearing on the affected side. It is unclear if these factors are a precursor to, or the result of the condition (6).

Other factors that may increase the likelihood of developing Severs disease include gastroc/ soleus weakness, joint hypomobility, poor lower extremity biomechanics- especially excessive foot pronation, inappropriate or excessive training, improper footwear, running on hard surfaces and excessive weight (7).

Although many clinicians consider Severs disease a clinical diagnosis, a study by Rachel found that greater than 5% of suspected calcaneal apophysitis patients had a more significant osseous lesion. The study suggested screening all suspected Severs patients with a lateral radiograph (8).

Plain films may be necessary to exclude conditions from a differential diagnosis including; fracture, avulsion, bone cyst, neoplasm or foreign body. Clinicians should be suspicious of ongoing pain, pain at rest, pain that awakens at night, significant swelling, fever, constitutional symptoms, or significant loss of subtalar motion. MRI may be of use to rule out osteomyelitis and CT will identify tarsal coalition.

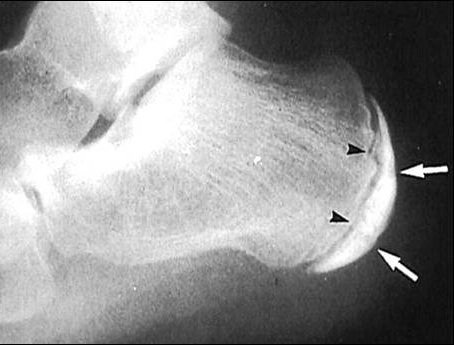

A study by Volpon described the primary radiographic finding for Severs disease as “fragmentation of the calcaneal apophysitis” (9). See the figures below.

Severs disease causes pain and limits athletic performance. If left untreated, the condition can significantly impact activities of daily living.

Treatment

The clinicians’ first goal is to allow a return to pain-free activity. Ice, especially pre- and post-activity, and anti-inflammatory modalities or NSAIDS are beneficial initially. Clinicians should address calf hypertonicity with myofascial release and stretching. Evaluate shoes and limit barefoot walking. Orthotics may be required to improve faulty foot biomechanics. The consistent use of ½ inch heel lifts (bilaterally) can ease shear strain from hypertonic calf muscles. Kinesiotaping of the posterior chain may provide benefits.

As youth sports become more competitive, adolescent athletes are subject to greater physical demands and their developing bodies sometimes fail to keep pace with the expectations of parents and coaches. Activity modification is often necessary. Reduction of the frequency and intensity of exercise, particularly the limitation of running and jumping activity may be required. Low-impact cross-training with a stationary bike or in the pool may be beneficial. Reassure patients and parents that calcaneal apophysitis is a self-limiting condition. Avoiding the term ‘disease” when discussing the condition may limit anxiety.

When the “squeeze test” is no longer painful, the treatment focus should shift to strengthening to improve biomechanics, thereby minimizing recurrence. Typically, symptoms resolve within 2 to 8 weeks of initiating rest and conservative treatment (10). In severe cases, a CAM walking brace may be necessary for 2-3 weeks (11).

Conclusion

There is limited evidence concerning the diagnosis and treatment of Severs disease. Most recommendations are based on anecdotal evidence. Like so many other musculoskeletal conditions, there is much to be learned regarding the management of Severs disease.

References

- Sever JW. Apophysitis of the os calcis. NY State J Med. 1912; 95:1025–9.

- Schwab SA. Epiphyseal injuries in the growing athlete. Can Med Assoc J 1977; 117: 626-630

- Micheli LJ, Ireland ML. Prevention and management of calcaneal apophysitis in children: an overuse syndrome. J Pediatr Orthop. Jan-Feb 1987;7(1):34-8.

- McKenzie DC, Taunton JE, Clement DB, et al. Calcaneal apophysitis in adolescent athletes. Can J Appl Sport Sci 6: 123, 1981.

- Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, Adams J. Rosen’s emergency medicine: concepts and clinical practice, 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby

- Becerro de Bengoa Vallejo R, Losa Iglesias ME, Plantar pressures in children with and without sever’s disease. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2011 Jan-Feb;101(1):17-24.

- Clemow C, Pope B, Woodall HE. Tools to speed your heel pain diagnosis. J Fam Pract. 2008;57(11):714-721.

- Rachel JN, Williams JB, Sawyer JR, Warner WC, Kelly Is radiographic evaluation necessary in children with a clinical diagnosis of calcaneal apophysitis (sever disease)?DMJ Pediatr Orthop. 2011 Jul-Aug;31(5):548-50.

- Volpon JB, de Carvalho Filho G. Calcaneal apophysitis: a quantitative radiographic evaluation of the secondary ossification center. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2002; 122(6):338–41

- Lee KT, Young KW, Park YU, et al. Neglected Sever’s disease as a cause of calcaneal apophyseal avulsion fracture: case report. Foot Ankle Int. 2010;31(8):725-8.

- Chiodo W, Cooke, K. Pediatric heel pain. Clin Pod Med Surg. 2010; 27(3):355-366.