Pelvic Floor Dysfunction

by: Tim Bertelsman & Brandon Steele, with significant contributions from ICS experts: Dr. Erika Mennerick, Dr. Cindy Howard, and Dr. Erin Ducat.

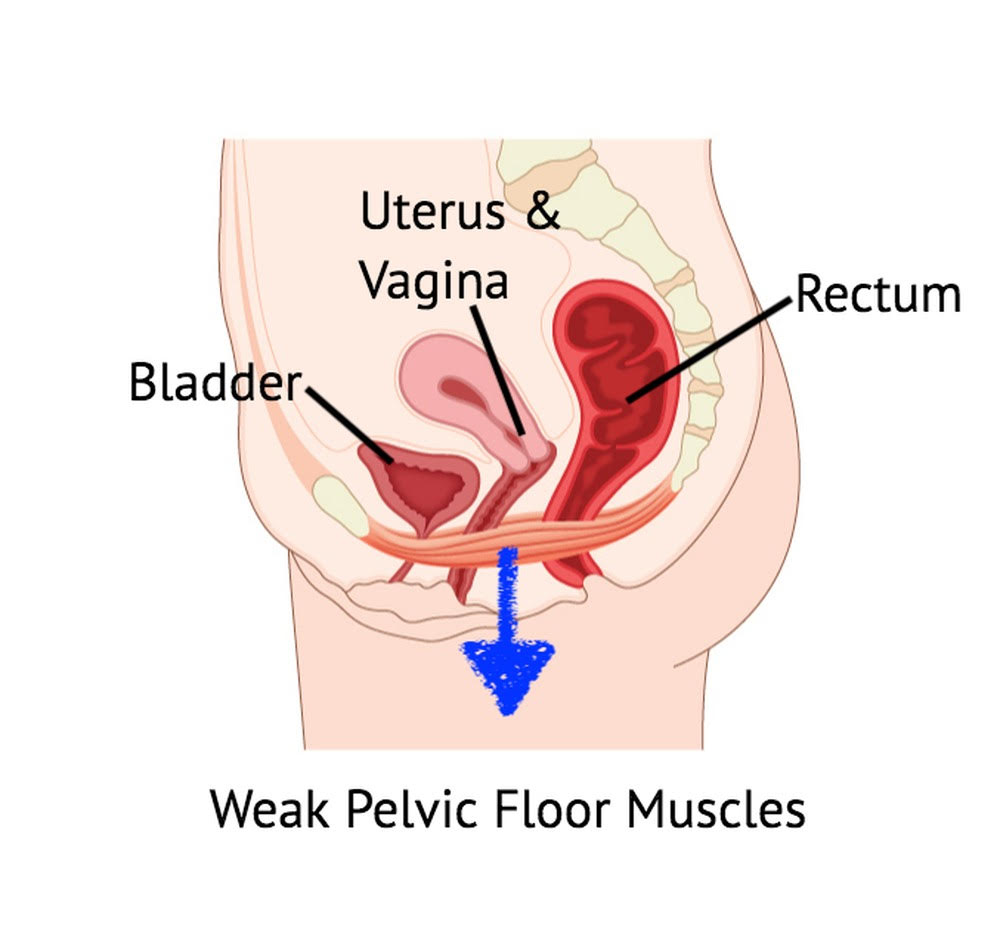

The pelvic floor is one of the body’s most complex anatomical and functional regions. (1) It serves to enclose the bony pelvic outlet and support the pelvic viscera while allowing controlled outlets for the rectum, urethra, and vagina. (2) Dysfunction of the pelvic floor muscles can produce a range of symptoms, including pain, incontinence, urgency, sexual dysfunction, and organ prolapse. Pelvic floor dysfunction is a frequently overlooked or ignored problem that significantly impacts personal, social, and work activities, mental well-being, and quality of life. (3-5)

The 3 Layers

The pelvic floor can be divided into three layers. (6) The internal layer consists of the peritoneum of the pelvic viscera. The external layer includes the skin of the vulva, scrotum, and perineum. The more robust middle layer comprises the endopelvic fascia and several muscles, including the urogenital sphincter, external anal sphincter, ischiocavernosus, bulbospongiosus, transverse perineal muscles, and levator ani group (pubococcygeus muscle, puborectalis, and iliococcygeus). (6,7) The hammock-shaped pelvic floor muscles attach anteriorly to the symphysis pubis and posteriorly to the coccyx. (7)

In addition to supporting the intestines, urinary bladder, and uterus, the pelvic floor muscles also function in unison to maintain bowel, bladder, and sexual function. (8-10) Voluntary contraction of the pelvic floor muscles lifts the pelvic contents and tightens orifices. (7) During pregnancy, the pelvic floor muscles support the developing fetus and assist with natural delivery. (8,11) Contraction of the sphincter muscles controls the release of the urine, feces, and gas, while relaxation (or the inability to maintain contraction) permits passage. (2,8,10) The pelvic floor muscles also play a significant role in sexual sensation and function for both genders. (10-13)

The pelvic floor contributes substantially to core stability. (71) Coordinated contraction of the pelvic floor muscles is necessary to pressurize the abdominal canister and generate spinal stability. (Please see the Chiro Up Spinal Instability Protocol for a more comprehensive explanation.)

Pelvic Floor Dysfunction

Like any other skeletal muscle, proper pelvic floor function requires the ability to contract both concentrically, as in a Kegel exercise, and eccentrically to accommodate the downward pressure of the diaphragm during inhalation. Pelvic floor dysfunction can arise when muscles are excessively stretched, damaged, or otherwise weakened, leading to stiff and distensile fibers that cannot generate power and sustained contraction. (15) Conversely, pelvic floor muscles can become hypertonic and overactive, causing rapid fatigue. (15) In addition to poor endurance, hypertonicity may result in excess pressure being placed on the bladder with subsequent incontinence. (16)

Estimates suggest that 1 in 4 women are affected by pelvic floor dysfunction (5,17,18) and 50% of women older than 50 years are affected by this condition worldwide, with a direct annual cost of $12 billion. (87-89) Unfortunately, only a small percentage seek medical help. (3) While females account for 95% of pelvic floor presentations, males are not immune and can experience symptoms including chronic pain, prostatitis, and sexual dysfunction. (16,19,20)

Urinary incontinence affects 18.3 million American women, while fecal incontinence impacts 10.6 million, and pelvic floor prolapse affects 3.3 million. (21) The incidence of pelvic floor dysfunction and its related symptoms are expected to increase markedly (35-64%) in future years. (21-23)

Childbirth

Vaginal childbirth is the primary risk factor for pelvic floor dysfunction. More than 90% of women demonstrate some form of pelvic floor injury following vaginal childbirth. (24) A single vaginal delivery increases the likelihood of prolapse ninefold; however, subsequent births do not seem to increase the odds substantially. (25) Delivery-associated risk multipliers include a prolonged second stage of labor, anal sphincter tear, and older maternal age. (24,26) Other contributors to pelvic floor dysfunction include prior surgery, physical or emotional trauma, sexual abuse, obesity, improper performance of Kegel exercises, quickly returning to heavy physical activity postpartum, constipation, a genetic predisposition for weak connective tissue or fascia, nerve damage, pathology (i.e., endometriosis, fibroids, pelvic inflammatory disease, ovarian cysts, ovarian remnant syndrome, vaginitis, hernia, prostatitis, etc.) hormonal changes, and menopause. (27,28)

Significant or repeated trauma can lead to progressive deterioration of the muscles and connective tissues, resulting in prolapse of internal organs. (21) Between 41- 50% of women over the age of 40 show some degree of pelvic organ prolapse. (3) Approximately 5-20% of females will undergo surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. (5,29,30) Between 20-30% of these women will require a repeat operation in the years that follow. (31-33)

Presentation

Pelvic floor dysfunction presents as a complex clinical picture with a spectrum of potential symptoms, including pain, urinary urgency or incontinence, fecal urgency or incontinence, sexual dysfunction, and pelvic organ prolapse. (2,14,34) Urinary incontinence affects 2/3 of those with pelvic floor dysfunction. (21) However, pelvic pain is the most likely presenting complaint in physical medicine clinics.

When evaluating any pelvic pain, manual therapists should seek to compassionately uncover any potentially related complaints, including bladder or bowel incontinence or GI/GU dysfunction. (18,35) Educating patients and their referring providers about the relevance of this line of questioning may be necessary. (36) The intake history should include a pertinent review of systems, including prior medical and obstetric histories. (37)

The myofascial symptoms of pelvic pain are often described as deep and achy, while rectal and clitoral pain can be sharp and piercing. (38,39) Vaginal symptoms may be described as burning. (38) Myofascial pain frequently affects the perineum, vagina, urethra, and rectum. (40) Referred pain may spread to the suprapubic region, lower abdomen, back, buttocks, and thorax. (40,41) Pelvic floor dysfunction may produce testicular pain in males. (41) Some patients may complain of urinary hesitancy, frequency, or even painful burning. (40,41) A report of chronic bloating is possible. (42) Symptoms are often provoked by urinary voiding, fecal defecation, menses, intercourse, and prolonged walking or sitting. (38,41,43) A sensation of incomplete defecation is not uncommon and may be due to a shortened puborectalis muscle encroaching on the anorectal angle. (38)

Management

Like any other muscle dysfunction syndrome, management hinges on identifying hypotonicity vs. hypertonicity as the primary culprit. Hypertonicity more commonly occurs in high-impact athletes such as runners, cyclists, weight lifters, etc. Hypotonicity often follows pregnancy and childbirth. However, clinicians should remember that diagnostic stereotypes are inherently unpredictable and should be viewed with caution.

Patients with hypertonic pelvic floors frequently report constipation, straining, and pain with intercourse or sexual stimulation, whereas patients with hypotonic pelvic floors complain more often of fecal or gas incontinence, or prolapse. (44) Urinary urgency or incontinence can be a sign of either dysfunction. (45) However, pelvic floor symptoms do not consistently correlate with physical exam findings (1); thus, confirmatory hands-on assessment is irreplaceable. (27)

Manual therapists should carefully consider whether they are the best-suited clinician for the hands-on assessment. Before embarking on any palpatory evaluation of the pelvic floor, examiners must weigh many factors, including scope of practice, training, informed consent, patient expectations, gender preferences, and liability issues. A specialty-trained pelvic floor physical therapist is the most common type of practitioner to perform an internal pelvic floor evaluation. (82)

Palpation of the pelvic floor can differentiate hypertonicity vs. hypotonicity and identify trigger points, which are common culprits for myofascial pain syndrome. The most frequently affected pelvic floor muscles include the pubovaginalis, puborectalis, iliococcygeus, coccygeus, anal sphincter, and obturator internus. (40)

Palpation of a supine patient could employ an around-the-clock pattern to identify tenderness or hypersensitive taut bands in the ischiocavernosus (1:00 and 11:00), bulbocavernosus (2:00 and 10:00), superficial transverse perineal muscles (3:00 and 9:00), anterior levator ani (4:00 and 8:00), and posterior levator ani (5:00 and 7:00). (46) Digital palpation can also confirm muscle function since self-perceived contractions are predictably unreliable. (44) Clinicians should assess for more distant myofascial involvement in the hips, legs, and torso.

Clinicians should screen for functional deficits that may perpetuate pelvic muscular discomfort, particularly hip abductor weakness, lower crossed syndrome, spinal instability, or dysfunctional breathing. (47,48)

Vaginal or anal manometry uses an inserted pressure sensor to quantify muscle contractility. (37,44) Manometry and dynamometry may be more reliable objective mechanisms to measure strength and contraction. (49) Not surprisingly, EMG assessment of patients with pelvic floor dysfunction demonstrates decreased activity and difficulty performing voluntary contraction of the affected muscles. (50) Real-time diagnostic ultrasound may help rule out soft tissue pathology and is also a reliable mechanism for assessing pelvic muscle contraction. (51) Advanced imaging, including MRI, may be necessary to narrow the broad list of differential diagnoses for pelvic pain. (2) MRI provides superior anatomic assessment of the regional structures, including ligaments, muscles and pelvic organs. Additionally, any underlying organic pathology potentially responsible for pelvic dysfunction can be more easily identified with MRI when compared to other modalities. More recently, the use of dynamic sequencing techniques provides an accurate means for identifying pelvic floor weakness, especially when multiple compartments are involved. (86)

Clinicians must recognize that pelvic pain frequently originates from pathology involving the gastrointestinal and genitourinary systems. (35,52) The differential diagnosis for pelvic pain includes urinary tract infection, endometriosis, fibroids, cysts, interstitial cystitis, prostate issues, colorectal lesions. (41,53,54)

Management of pelvic floor dysfunction can prove challenging, as evidenced by the fact that more than 40% of patients suffer from symptoms for more than five years. (3) If left untreated, the problem can be a significant deterrent to intimacy, work, and social functions. (18) The associated symptoms can lead to depression, isolation, and anxiety. (3)

Conservative management of pelvic floor dysfunction consists of myofascial techniques, rehabilitation exercise, and lifestyle advice. Proper management often requires a coordinated multi-disciplinary team to resolve all components, including any underlying comorbidities. (1)

Pelvic floor rehabilitation must be specifically tailored to the patient’s needs. (55) Patients with weak or hypotonic vaginal and anal muscles may benefit from Kegel-type exercises, whereas those with hypertonicity might be better served by techniques like manual therapy, scar tissue manipulation, modalities (ultrasound, e-stim), massage, dilators, breathing re-training, cognitive behavioral therapy, and meditation. (42,44)

Kegel Exercise

Kegel exercises remain the most popular choice of rehab for patients with pelvic floor weakness. Kegel exercises meet the three-main principles of effective muscle training: overload (perform more work than usual), specificity (replicate functional demands), and reversibility (ongoing training required to sustain benefit). (28,56) However, Kegel exercises may worsen cases of hypertonicity and should only be applied when internal palpation has proved necessity and that the exercises are being performed appropriately. (36)

Patients may perform Kegel exercises in any position; however, most find greatest ease while sitting. Patients performing Kegel exercises contract the muscles that stop or slow urination by imagining that they are squeezing and lifting a tampon or marble. (57,58) Similar contractions can be repeated for the anal muscles. Kegel exercises can be performed via both short 1-2 second contractions and longer 10-20 second holds. There is no consensus on the frequency of performing pelvic floor strengthening exercises, and recommendations range between 5 and 200 repetitions per day. (59,60) Some experts advocate for 30 successive short-hold repetitions to the point of fatigue. (27)

Proper instruction and exercise monitoring are essential, as most women with pelvic floor dysfunction have an inaccurate self-perception of pelvic floor muscle contraction. (61) Many patients will often incorrectly bear down, performing a Valsalva maneuver instead of a Kegel.

If a Kegel has been deemed appropriate, manual monitoring by the clinician or internal self-assessment by the patient can confirm a proper lift and squeeze technique. Vaginal or anal electromyography and biofeedback are alternate means of monitoring muscular activity. (37) Compared to manual monitoring, biofeedback devices may enhance the effectiveness of Kegel exercises. (79-81)

One of the quandaries for prescribing Kegel exercises is that a hands-on pelvic exam is essential, however, very few practitioners are qualified and willing to provide that service. Fortunately, core and eccentric pelvic floor training exercises are alternatives to Kegel exercises that may benefit patients with either hypertonicity and hypotonicity.

Movement and balance exercises can be performed in the seated or supine position. Rehab should target the inner core muscles including the pelvic floor and transverse abdominis. Options could include pelvic tilt, pelvic clock, and V-sit exercises. Dynamic stability exercises for the inner core can be performed on a rocker-type board to promote movement of the pelvis in all planes. (85)

The dynamic neuromuscular stabilization bear position allows patients to manage intra-abdominal pressure with the pelvic floor in an elevated position while limiting the tendency to bear down. This allows for eccentric control of the pelvic floor and simultaneous pressurization of the core canister. (36)

Patients with pelvic floor dysfunction often present with paradoxical breathing patterns, so instruction of proper diaphragmatic breathing is crucial. Proper diaphragmatic breathing helps to improve pelvic floor relaxation and allows better coordinated function for overall canister stability. (36)

Pelvic floor muscle training performed for three months can lead to significant quality of life improvements. (62) Women who perform pelvic floor muscle training are five times more likely to report resolution of urinary incontinence. (58) Kegel exercises, when appropriate, have been shown to improve sexual function in both genders (59), including symptoms of erectile dysfunction in men. (16,19)

Similar to the earlier concerns about hands-on palpation, manual therapy procedures deserve a careful appraisal of appropriateness. Myofascial release has shown benefit for pelvic myofascial pain syndrome, particularly in hypertonic patients. (38,63,73) Dry needling, where allowed, may be a helpful technique for reducing myofascial involvement. (83) Studies on Pulsed Electromagnetic Field therapy (PEMF) applied over the sacral nerve roots have shown merit for managing urinary incontinence. (75-77) Extracorporeal Shockwave Therapy (ESWT) is another potentially helpful modality for pelvic floor dysfunction. (78) HVLA manipulation of the pelvis and lumbosacral region has been shown to affect the strength and tone of pelvic floor muscles (27) Acupuncture may be helpful. (42)

Concurrent general aerobic training may enhance outcomes for pelvic floor rehab. (55,64) Regular aerobic exercise may also help maintain improvements achieved through pelvic muscle training. (42) Incorporating Pilates and yoga may be useful adjuncts. (65)

Patient education is a crucial component of recovery. (26) Clinicians must provide a potent rationale and motivation for home exercise. Patients may be taught controlled fluid intake and timed urination skills, although some patients may not respond to bladder training. (36) The natural tendency to avoid fluids can lead to dehydration and subsequent muscle dysfunction. Patients must understand the importance of diet, including limiting caffeine, alcohol, artificial sweeteners, and inflammatory or gas-producing foods. (66) Stress management may be appropriate for some cases. Most importantly, providers must provide an environment of support, empathy, and compassion so that patients are comfortable discussing their concerns.

Pharmacologic considerations include medication for overactive bladder and hormonal deficits. (67,68) Trigger point injections, including Botox®, may help ease the pain of myofascial trigger points. Pudendal nerve blocks or pudendal neuromodulation are considerations. (42) Surgery, including mesh slings, which have come under strong scrutiny in recent years (74) may be necessary when other more conservative measures fail. (69,70)

References

1. Shannon MB, Mueller ER. Pelvic Pain Associated with a Gynecologic Etiology. InPelvic Floor Disorders 2021 (pp. 879-889). Springer, Cham.

2. Reiner CS, Schawkat K. Dynamic Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Pelvic Floor Pathologies. InPelvic Floor Disorders 2021 (pp. 653-660). Springer, Cham. Link

3. Bedretdinova D, Fritel X, Zins M, Ringa V. The effect of urinary incontinence on health-related quality of life: is it similar in men and women?. Urology. 2016 May 1;91:83-9. Link

4. Jantos M. A Myofascial Perspective on Chronic Urogenital Pain in Women. InPelvic Floor Disorders 2021 (pp. 923-943). Springer, Cham. Link

5. Dieter AA, Wilkins MF, Wu JM. Epidemiological trends and future care needs for pelvic floor disorders. Current opinion in obstetrics & gynecology. 2015 Oct;27(5):380. Link

6. Messelink B, Benson T, Berghmans B, Bo K, Corcos J, Fowler C, Laycock J, Lim PH, van Lunsen R, Nijeholt GA. Standardization of terminology of pelvic floor muscle function and dysfunction: report from the pelvic floor clinical assessment group of the International Continence Society. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2005 Jan 1;24(4):374. Link

7. Theodorsen NM, Strand LI, Bø K. Effect of pelvic floor and transversus abdominis muscle contraction on inter-rectus distance in postpartum women: a cross-sectional experimental study. Physiotherapy. 2019 Sep 1;105(3):315-20. Link

8. Continence Foundation of Australia. 2018. Pelvic Floor Muscles in Men. Accessed 3/12/2021 from: Link

10 . Foundation Physiotherapy. 2018. 5 Basic Functions of your Pelvic Floor. Accessed 03/12/2021 from: Link

11. Theodorsen NM, Strand LI, Bø K. Effect of pelvic floor and transversus abdominis muscle contraction on inter-rectus distance in postpartum women: a cross-sectional experimental study. Physiotherapy. 2019 Sep 1;105(3):315-20. Link

12. The Male Pelvic Floor. Physiopedia. Accessed 03/1/2021 from: Link

13. Lowenstein L, Gruenwald I, Gartman I, Vardi Y. Can stronger pelvic muscle floor improve sexual function? International Urogynecology Journal. 2010 May;21(5):553-6. Link

14. Nygaard I, Barber MD, Burgio KL, Kenton K, Meikle S, Schaffer J, Spino C, Whitehead WE, Wu J, Brody DJ, Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. Jama. 2008 Sep 17;300(11):1311-6. Link

15. Marques A, Stothers L, Macnab A. The status of pelvic floor muscle training for women. Canadian Urological Association Journal. 2010 Dec;4(6):419. Link

16. Cohen D, Gonzalez J, Goldstein I. The role of pelvic floor muscles in male sexual dysfunction and pelvic pain. Sexual medicine reviews. 2016 Jan 1;4(1):53-62. Link

17. Nygaard I, Barber MD, Burgio KL, Kenton K, Meikle S, Schaffer J, Spino C, Whitehead WE, Wu J, Brody DJ, Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. Jama. 2008 Sep 17;300(11):1311–6. Link

18. Harvey MA. Pelvic floor exercises during and after pregnancy: a systematic review of their role in preventing pelvic floor dysfunction. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 2003 Jun 1;25(6):487-98. Link

19. Theodorsen NM, Strand LI, Bø K. Effect of pelvic floor and transversus abdominis muscle contraction on inter-rectus distance in postpartum women: a cross-sectional experimental study. Physiotherapy. 2019 Sep 1;105(3):315-20. Link

20. Kavvadias T, Baessler K, Schuessler B. Pelvic pain in urogynaecology. Part I: evaluation, definitions and diagnoses. International urogynecology journal. 2011 Apr;22(4):385-93. Link

21. Shannon MB, Mueller ER. Pelvic Pain Associated with a Gynecologic Etiology. InPelvic Floor Disorders 2021 (pp. 879-889). Springer, Cham.

22. Berghmans B, Nieman F, Leue C, Weemhoff M, Breukink S, Van Koeveringe G. Prevalence and triage of first contact pelvic floor dysfunction complaints in male patients referred to a Pelvic Care Centre. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2016 Apr;35(4):487-91. Link

23. Kirby AC, Luber KM, Menefee SA. An update on the current and future demand for care of pelvic floor disorders in the United States. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2013 Dec 1;209(6):584-e1. Link

24. Nygaard I. New directions in understanding how the pelvic floor prepares for and recovers from vaginal delivery. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2015 Aug 1;213(2):121-2. Link

25. Quiroz LH, Muñoz A, Shippey SH, Gutman RE, Handa VL. Vaginal parity and pelvic organ prolapse. The Journal of reproductive medicine. 2010 Mar;55(3-4):93. Link

26. Memon H, Handa VL. Pelvic floor disorders following vaginal or cesarean delivery. Current opinion in obstetrics & gynecology. 2012 Oct;24(5):349. Link

27. de Almeida BS, Sabatino JH, Giraldo PC. Effects of high-velocity, low-amplitude spinal manipulation on strength and the basal tonus of female pelvic floor muscles. Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics. 2010 Feb 1;33(2):109-16. Link

28. Marques A, Stothers L, Macnab A. The status of pelvic floor muscle training for women. Canadian Urological Association Journal. 2010 Dec;4(6):419. Link

29. Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1997 Apr 1;89(4):501-6. Link

30. Smith FJ, Holman CA, Moorin RE, Tsokos N. Lifetime risk of undergoing surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2010 Nov 1;116(5):1096-100. Link

31. Denman MA, Gregory WT, Boyles SH, Smith V, Edwards SR, Clark AL. Reoperation 10 years after surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2008 May 1;198(5):555-e1. Link

32. Fialkow MF, Newton KM, Weiss NS. Incidence of recurrent pelvic organ prolapse 10 years following primary surgical management: a retrospective cohort study. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19(11):1483–7. Link

33. Abdel-Fattah M, Familusi A, Fielding S, Ford J, Bhattacharya S. Primary and repeat surgical treatment for female pelvic organ prolapse and incontinence in parous women in the UK: a register linkage study. BMJ open. 2011 Jan 1;1(2). Link

34. Pedraza R, Nieto J, Ibarra S, Haas EM. Pelvic muscle rehabilitation: a standardized protocol for pelvic floor dysfunction. Advances in urology. 2014 Oct;2014. Link

35. Cerruto MA. Chronic Pelvic Pain and Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome: Classification and Epidemiology. InChronic Pelvic Pain and Pelvic Dysfunctions 2021 (pp. 49-60). Springer, Cham. Link

36. Mumma, L. RE: “Pelvic Floor Dysfunction Protocol.” Message to Tim Bertelsman regarding advice on chiropractic management of pelvic floor dysfunction patients via direct email on 03/09/2021.

37. Pedraza R, Nieto J, Ibarra S, Haas EM. Pelvic muscle rehabilitation: a standardized protocol for pelvic floor dysfunction. Advances in urology. 2014 Oct;2014. Link

38. Pastore EA, Katzman WB. Recognizing myofascial pelvic pain in the female patient with chronic pelvic pain. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing. 2012 Sep 1;41(5):680-91. Link

39. Dommerholt J, Bron C, Franssen J. Myofascial trigger points: an evidence-informed review. Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy. 2006 Oct 1;14(4):203-21. Link

40. Simons DG, Travell JG, Simons LS. Travell and Simon’ myofascial pain and dysfunction: The trigger point manual. 2nd ed. Vol. 2. Williams and Wilkins; London: 1999b.

41. Trigger Point Therapy for Pelvic Pain. Medical College of Wisconsin- Obstetrics & Gynecology Department. Accessed 02/27/2021 from: Link

42. Howard C. RE: “Pelvic Floor Dysfunction Protocol.” Message to Tim Bertelsman regarding advice on chiropractic management of pelvic floor dysfunction patients via direct email on 03/04/2021.

43. Butrick CW. Pelvic floor hypertonic disorders: identification and management. Obstetrics and gynecology clinics of North America. 2009 Sep 1;36(3):707-22. Link

44. Vandyken, C. Pelvic Physiotherapy- to Kegel of Not? Pelvic Health Solutions. Accessed 02/27/21 from: Link

45. Mennerick E. RE: “Pelvic Floor Dysfunction Protocol.” Message to Tim Bertelsman regarding advice on chiropractic management of pelvic floor dysfunction patients via direct email on 03/02/2021.

46. Apte G, Nelson P, Brismée JM, Dedrick G, Justiz III R, Sizer Jr PS. Chronic female pelvic pain—part 1: clinical pathoanatomy and examination of the pelvic region. Pain Practice. 2012 Feb;12(2):88-110. Link

47. Neville C, Mallinson T, Badillo SA, Fitzgerald CM, Hynes C, Tu F. Comparison of PT and MD Findings of Physical Examination of Patients With and With-out Chronic Pelvic Pain. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy. 2009 Apr 1;33(1):16. Link

48. Tu FF, Holt J, Gonzales J, Fitzgerald CM. Physical therapy evaluation of patients with chronic pelvic pain: a controlled study. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2008 Mar 1;198(3):272-e1. Link

49. Navarro Brazález B, Torres Lacomba M, de la Villa P, Sanchez Sanchez B, Prieto Gómez V, Asúnsolo del Barco Á, McLean L. The evaluation of pelvic floor muscle strength in women with pelvic floor dysfunction: a reliability and correlation study. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2018 Jan;37(1):269-77. Link

50. Ribeiro AM, Nammur LG, Mateus-Vasconcelos EC, Ferreira CH, Muglia VF, Oliveira HF. Pelvic floor muscles after prostate radiation therapy: morpho-functional assessment by magnetic resonance imaging, surface electromyography and digital anal palpation. International braz j urol. 2021 Feb;47(1):120-30. Link

51. Thompson JA, O’Sullivan PB, Briffa K, Neumann P. Assessment of pelvic floor movement using transabdominal and transperineal ultrasound. International Urogynecology Journal. 2005 Aug;16(4):285-92. Link

52. Bazzocchi G, Balloni M, Turroni S. Microbiome and Chronic Pelvic Pain. InChronic Pelvic Pain and Pelvic Dysfunctions 2021 (pp. 145-159). Springer, Cham. Link

53. Apte G, Nelson P, Brismée JM, Dedrick G, Justiz III R, Sizer Jr PS. Chronic female pelvic pain—part 1: clinical pathoanatomy and examination of the pelvic region. Pain Practice. 2012 Feb;12(2):88-110. Link

54. Butrick CW. Pelvic floor hypertonic disorders: identification and management. Obstetrics and gynecology clinics of North America. 2009 Sep 1;36(3):707-22. Link

55. Marques A, Stothers L, Macnab A. The status of pelvic floor muscle training for women. Canadian Urological Association Journal. 2010 Dec;4(6):419. Link

56. Laycock J. Concepts of neuromuscular rehabilitation and pelvic floor muscle training. InPelvic floor re-education 2008 (pp. 177-183). Springer, London. Link

57. Huang YC, Chang KV. Kegel Exercises. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2020 Jan.

58. Uechi N, Fernandes AC, Bø K, de Freitas LM, de la Ossa AM, Bueno SM, Ferreira CH. Do women have an accurate perception of their pelvic floor muscle contraction? A cross‐sectional study. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2020 Jan;39(1):361-6. Link

59. Mohktar MS, Ibrahim F, Rozi NF, Yusof JM, Ahmad SA, Yen KS, Omar SZ. A quantitative approach to measure women’s sexual function using electromyography: A preliminary study of the Kegel exercise. Medical science monitor: international medical journal of experimental and clinical research. 2013;19:1159. Link

60. Marques A, Stothers L, Macnab A. The status of pelvic floor muscle training for women. Canadian Urological Association Journal. 2010 Dec;4(6):419. Link

61. Uechi N, Fernandes AC, Bø K, de Freitas LM, de la Ossa AM, Bueno SM, Ferreira CH. Do women have an accurate perception of their pelvic floor muscle contraction? A cross‐sectional study. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2020 Jan;39(1):361-6. Link

62. Fitz FF, Costa TF, Yamamoto DM, Resende AP, Stüpp L, Sartori MG, Girão MJ, Castro RA. Impact of pelvic floor muscle training on the quality of life in women with urinary incontinence. Revista da Associação Médica Brasileira (English Edition). 2012 Mar 1;58(2):155-9. Link

63. FitzGerald MP, Anderson RU, Potts J, Payne CK, Peters KM, Clemens J, …Nyberg L. Randomized multicenter feasibility trial of myofascial physical therapy for the treatment of urological chronic pelvic pain syndromes. The Journal of Urology. 2009;182(2):570–580.

64. Sapsford RR, Hodges PW. Contraction of the pelvic floor muscles during abdominal maneuvers. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2001 Aug 1;82(8):1081-8. Link

65. Baessler K, Schüssler B, Burgio KL, Moore KH, Norton PA, Stanton SL. Pelvic floor re-education. London: Springer. 2008. Link

66. Bharucha AE, Chakraborty S, Sletten CD. Common functional gastroenterological disorders associated with abdominal pain. InMayo Clinic proceedings 2016 Aug 1 (Vol. 91, No. 8, pp. 1118-1132). Elsevier. Link

67. Ayeleke RO, Hay‐Smith EJ, Omar MI. Pelvic floor muscle training added to another active treatment versus the same active treatment alone for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013(11). Link

68. NHS., 2021. Urinary Incontinence. [online]. Accessed 3/12/2021 from: Link

69. Maxwell M, Semple K, Wane S, Elders A, Duncan E, Abhyankar P, Wilkinson J, Tincello D, Calveley E, MacFarlane M, McClurg D. PROPEL: implementation of an evidence based pelvic floor muscle training intervention for women with pelvic organ prolapse: a realist evaluation and outcomes study protocol. BMC health services research. 2017 Dec;17(1):1-0. Link

70. NHS, 2021. Urinary Incontinence – Accessed 03/04/2021 from: Link

71. Sapsford R. Rehabilitation of pelvic floor muscles utilizing trunk stabilization. Manual therapy. 2004 Feb 1;9(1):3-12. Link

72. Bø K, Talseth T, Holme I. Single blind, randomised controlled trial of pelvic floor exercises, electrical stimulation, vaginal cones, and no treatment in management of genuine stress incontinence in women. Bmj. 1999 Feb 20;318(7182):487-93. Link

73. FitzGerald MP, Payne CK, Lukacz ES, Yang CC, Peters KM, Chai TC, Nickel JC, Hanno PM, Kreder KJ, Burks DA, Mayer R. Randomized multicenter clinical trial of myofascial physical therapy in women with interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome and pelvic floor tenderness. The Journal of urology. 2012 Jun;187(6):2113-8. Link

74. Whooley J, Cunnane EM, Do Amaral R, Joyce M, MacCraith E, Flood HD, O’Brien FJ, Davis NF. Stress urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse: Biologic graft materials revisited. Tissue Engineering Part B: Reviews. 2020 Oct 1;26(5):475-83. Link

75. Lim R, Liong ML, Leong WS, Khan NA, Yuen KH. Pulsed magnetic stimulation for stress urinary incontinence: 1-year followup results. The Journal of urology. 2017 May 1;197(5):1302-8. Link

76. But I. Conservative treatment of female urinary incontinence with functional magnetic stimulation. Urology. 2003 Mar 1;61(3):558-61. Link

77. Yamanishi T, Homma Y, Nishizawa O, Yasuda K, Yokoyama O, SMN‐X study group. Multicenter, randomized, sham‐controlled study on the efficacy of magnetic stimulation for women with urgency urinary incontinence. International Journal of Urology. 2014 Apr;21(4):395-400. Link

78. Long CY, Lin KL, Lee YC, Chuang SM, Lu JH, Wu BN, Chueh KS, Ker CR, Shen MC, Juan YS. Therapeutic effects of low intensity extracorporeal low energy shock wave therapy (LiESWT) on stress urinary incontinence. Scientific reports. 2020 Apr 2;10(1):1-0. Link

79. Burgio KL, Robinson JC, Engel BT. The role of biofeedback in Kegel exercise training for stress urinary incontinence. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1986 Jan 1;154(1):58-64. Link

80. Tries J. Kegel exercises enhanced by biofeedback. Journal of enterostomal therapy. 1990 Mar 1;17(2):67-76. Link

81. Vickers D, Davila GW. Kegel exercises and biofeedback. InPelvic Floor Dysfunction 2008 (pp. 303-310). Springer, London. Link

82. Wallace SL, Miller LD, Mishra K. Pelvic floor physical therapy in the treatment of pelvic floor dysfunction in women. Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2019 Dec 1;31(6):485-93. Link

83. Connor K.Geletka B. Dry Needling for Pelvic Dysfunction? University Hospitals. February 25, 2020 Accessed 03/16/21 from: https://www.uhhospitals.org/for-clinicians/articles-and-news/articles/2020/02/dry-needling-for-pelvic-dysfunction

84. Hyde T. RE: “Pelvic Floor Dysfunction Protocol.” Message to Tim Bertelsman regarding advice on chiropractic management of pelvic floor dysfunction patients via direct email on 03/14/2021.

85. Tucker J. RE: “Pelvic Floor Dysfunction Protocol.” Message to Tim Bertelsman regarding advice on chiropractic management of pelvic floor dysfunction patients via direct email on 03/15/2021.

86. Barry M. RE: “Pelvic Floor Dysfunction Protocol.” Message to Tim Bertelsman regarding advice on chiropractic management of pelvic floor dysfunction patients via direct email on 03/17/2021.

87. Molander U, Milsom I, Ekelund P, Mellström D. An epidemiological study of urinary incontinence and related urogenital symptoms in elderly women. Maturitas 1990;12(1):51–60. Link

88. Thom D. Variation in estimates of urinary incontinence prevalence in the community: effects of differences in definition, population characteristics, and study type. J Am Geriatr Soc 1998;46(4):473–480. Link

89. Wilson L, Brown JS, Shin GP, Luc KO, Subak LL. Annual direct cost of urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol 2001;98(3):398–406. Link