Kummell’s Disease (Delayed Vertebral Body Compression Fracture)

Kummell’s disease manifests as a delayed collapse of a vertebral body, post-trauma. This condition was first noted by the German physician Hermann Kummell in 1891. The condition has been considered for many years to be a form of ischemic necrosis of the vertebral body. Avascular necrosis of a vertebral body is fairly rare as a stand-alone occurrence. It is currently recognized that the incidence of Kummel’s disease actually represents the development of a delayed compression fracture and subsequent development of ischemic necrosis (1). Initially the images of the vertebral body appear normal and without any loss of vertebral body height. The patient may not even remember the episode of trauma, as it may have seemed trivial at the time. Over a period of days to weeks, there is a progressive collapse of the vertebral body. The degree of compression may be rapid and severe.

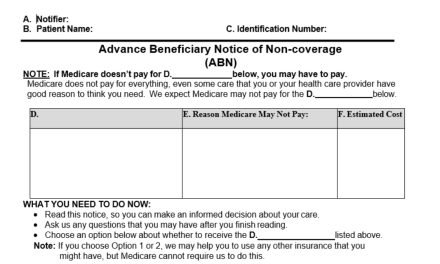

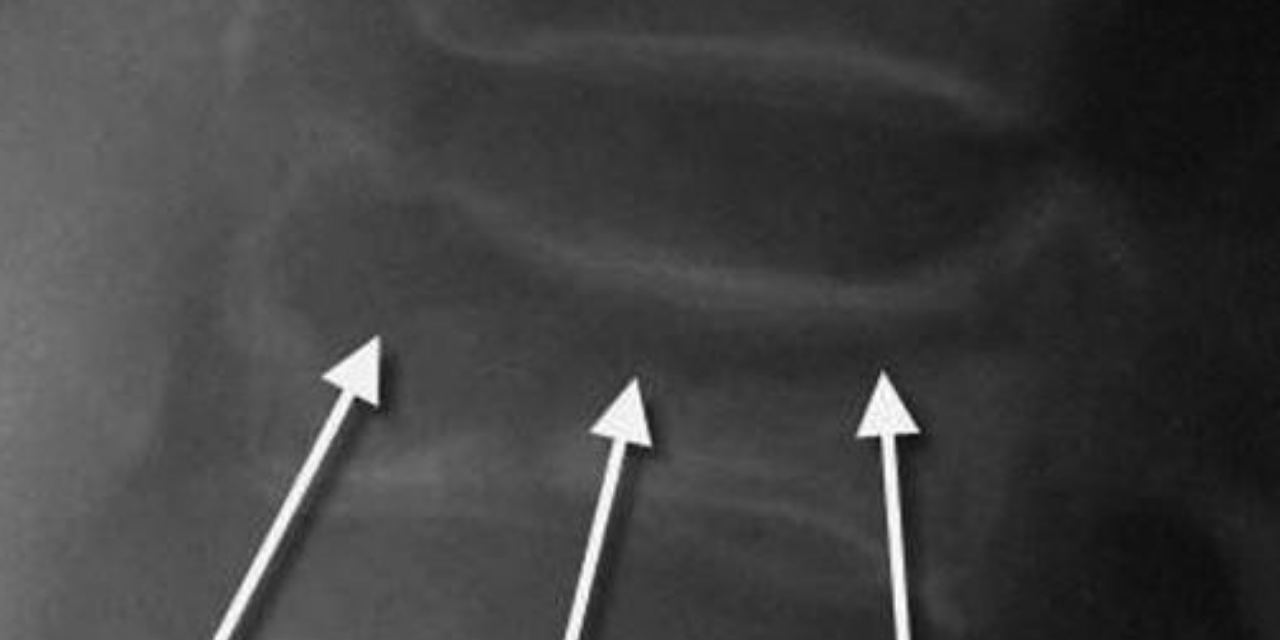

Plain film radiographs may reveal only the progressive vertebral body collapse. Vertebral body compression, however, can have various causes, not the least of which is malignancy, either primary or metastatic. Underlying causes, such as malignancy or marrow replacement diseases, must be excluded. Fortunately, there is a sign that is usually readily seen on both CT or MRI (and sometimes be seen on plain film x-ray as well) that is supportive of Kummell’s disease rather than these other conditions This is the presence of an intraosseous vacuum cleft sign (2) which can be seen on advanced imaging. This cleft represents a collection of gas (air) within the vertebral body.

Figure 1 shows the presence of gas within a collapsed vertebral body on a lateral plain film x-ray image.

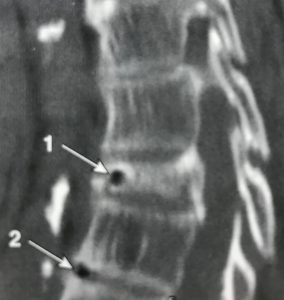

Figure 2 demonstrates gas within a thoracic spine segment (arrow 1) on a sagittal CT image, indicative of Kummell’s disease. There is gas within the anterior aspect of the intervertebral disc (arrow 2), which is representative of degeneration within the disc and should not be confused with the intraosseous gas of Kummell’s disease.

In figures 3 and 4 (T1 and T2 weighted sagittal images on MRI of lower thoracic spine), an arrow indicates the low signal intensity of gas within the anterior aspect of the vertebral body. There is retropulsion of the posterior aspect of the vertebral body.

Figure 5 is a fat-suppressed image, which highlights fluid surrounding the gas collection. This is manifested with high signal intensity (arrows 1) surrounding the low signal intensity gas (arrow 2). When undergoing MRI, these fluid collections may occur.

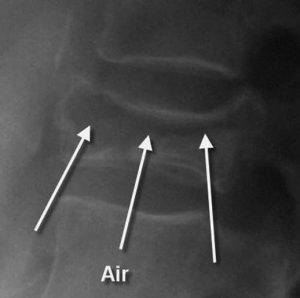

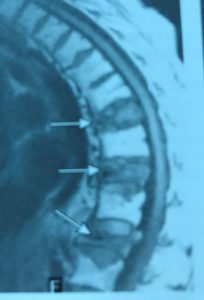

Figure 6 demonstrates multiple Kummell’s disease compression deformities on a T1 weighted image. Low signal intensity foci are seen anteriorly in these vertebral segments (indicated by the arrows).

Treatment options for delayed vertebral body collapse include vertebroplasty or stabilization.

References

1. Renfrew D.L.: Atlas of Spine Imaging, Philadelphia, Elsevier Science, 2003

- Yochum T.R.,Rowe L.J.: Essentials of Skeletal Radiology, ed 3. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005