Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis

In chiropractic college radiology classes, we learned about many arthritic disorders. Some, like degenerative joint disease, are very common. Others, septic joint infection for instance, are not so common. There is a type of arthritis, however, that often goes undiagnosed; yet it, as in the words of one of my esteemed colleagues, is “as common as dirt.”

Radiographic Criteria for DISH

Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis, more commonly referred to as DISH, is often confused or misdiagnosed as a degenerative change in the spine. Next, to degenerative disc disease and the associated spondylosis, DISH is the most common spinal arthropathy that I see in my radiology practice. One of the reasons that it often goes undiagnosed is the fact that the radiographic criteria for this condition are rather strict, and technically if these criteria are not met, the diagnosis should not be made. The radiographic criteria as spelled out in Yochum and Rowe “Essentials of Skeletal Radiology” (1) are as follows:

- Flowing calcification along the anterolateral aspect of at least four contiguous vertebral bodies.

- Relative preservation of the intervertebral disc height of the involved segments with lack of other associated signs of disc degeneration.

- Absence of apophyseal joint ankylosis and sacroiliac erosion, sclerosis or intra-articular osseous fusion.

The strict criteria were designed to exclude cases of the simple degenerative disc disease and the seronegative spondyloarthropathies, even though there may be many cases of DISH that go undiagnosed because they may not exhibit all of the criteria. In fact, there are many cases of DISH that do not meet these strict radiographic criteria, and it is essential to recognize this condition even when all the criteria are not met.

Structures Involved in Spinal DISH.

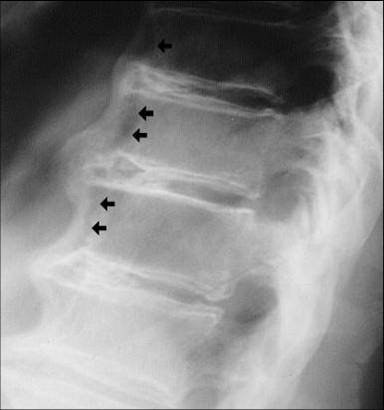

Patients with DISH are often said to be bone formers. This means they have a propensity to form bone in ligamentous and tendinous structures. In the spine, DISH involves ossification of the anterior longitudinal ligament (ALL) and sometimes the posterior longitudinal ligament (PLL). ALL ossification results in the typical anterior flowing hyperostosis that is characteristic of DISH and extends from the midpoint of one vertebral body to that of the next (Fig.1). This can range from very thick ossific masses to finer ossifications that may be very similar in appearance to that seen in ankylosing spondylitis. The ossification may be discontinuous at certain points which may allow a degree of intersegmental motion in an otherwise fused segment of the spine.

Figure 1

Figure 2

DISH tends to be most common in the thoracic spine, and typically the ossifications involve the anterior and right lateral portion of the vertebral bodies (Fig.2). Left-sided involvement is markedly less common. This has been postulated as being due to the pulsating effect of the thoracic aorta on the left side which may retard the formation of bone in that area.

Cervical spine involvement is somewhat less common than the thoracic spine. The potential adverse effects of this condition are more pronounced in the cervical spine, however. If the ossification is very thick, it may interfere with swallowing as the mass may displace the esophagus anteriorly (Fig.3).

A potentially more serious complication is ossification of the PLL in the cervical spine. On plain film radiography, this may appear as a longitudinal stripe of density paralleling the posterior aspect of the vertebral bodies (Fig.4),

Figure 4

Figure 5

and it can act as a space-occupying lesion resulting in varying degrees of central canal stenosis. This effect may be best visualized on CT (Fig.5).

Additionally, myelopathy may result from the chronic presence of this ossific mass and subsequent pressure on the spinal cord.

Involvement of the lumbar spine is similar in appearance to the thoracic spine with the exception that the relative lack of involvement of the left side of the thoracic spine is not seen in the lumbar spine. To aid in making the diagnosis in the lumbar spine, there may be involvement of the sacroiliac joints. This is manifested as an increase in density involving the upper third of the joint. Also, there may be a degree of calcification of the sacroiliac ligaments which provides the increased density. The joint is otherwise unaffected and there is no erosive change, which helps to exclude inflammatory etiologies, like ankylosing spondylitis.

Hidden DISH Findings

When the strict radiographic criteria are met, the diagnosis of DISH is fairly straightforward. Often, however, the radiographic findings of DISH are superimposed upon a pre-existing degenerative change in the spine. Although under these circumstances the strict DISH criteria may not be met, DISH may still be present. Thus, it is important to recognize the preponderance of DISH radiographic findings and to consider its possible future consequences.

DISH may be progressive, and a relatively limited area of involvement may become more extensive with time. Additionally, there may be a progressive decrease in spinal range of motion. Efforts to manipulate a fused segment of the spine may at best be unsuccessful and at worst, fracture a fused segment of the spine. DISH symptoms may be somewhat variable overall, and they tend to be chronic and low grade. There is also a higher rate of adult onset diabetes in DISH patients, and this correlation should always be kept in mind.

In conclusion, DISH is a fairly common disorder in the spine, and it must be differentiated from the seronegative spondyloarthropathies. It is often found in combination with degenerative disc disease which may make the diagnosis more difficult. Lastly, if you see DISH in any part of the spine, you should rule out OPLL in the cervical spine.

References

Yochum T.R., Rowe L.J.: Essentials of Skeletal Radiology, ed 3. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005