Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

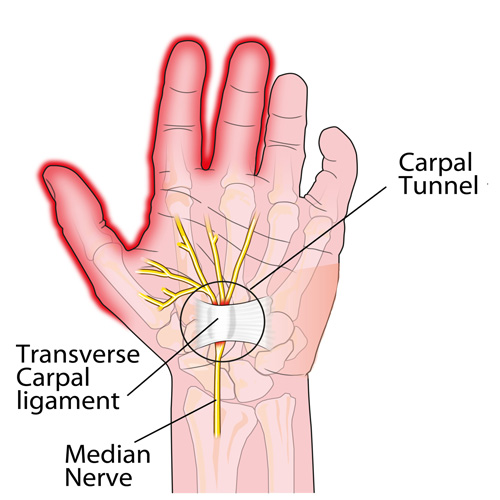

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is caused by mechanical compression of the median nerve within the carpal tunnel. This compression causes local ischemia and results in sensory and/or motor deficits in the distribution of the median nerve.

CTS is the most common nerve entrapment, with a reported prevalence of 3-5% in the general population (1,2). The condition has a female-to-male ratio of at least 2 or 3:1 (3,4). The peak incidence of CTS is adults age 45-60 (5). White adults are affected 2-3 times more commonly than black adults (6).

Extrinsic Factors

Median nerve compression can occur from a variety of etiologies, and multiple risk factors are often present. Extrinsic factors are often task-related and include prolonged wrist flexion or extension, repetitive wrist movements, i.e. supermarket checker, and exposure to vibration or cold (7,8). Those working on an assembly line are at much higher risk for developing CTS than data entry personnel (9). CTS is rare in developing countries, as repetitive work environments are uncommon. CTS is more common in the dominant hand, and bilateral symptoms are not unusual (9).

In addition to age, race, and gender, intrinsic risk factors for CTS include: diabetes, hypothyroidism, rheumatoid arthritis, alcoholism, increased BMI (especially recent increases), renal disease and short stature (10). Prior trauma resulting in fracture, dislocation, or osteoarthritis, may narrow the canal. Fluid retention during pregnancy is a cause of transient CTS symptoms.

Other compressive factors include a thickened transverse ligament or possessing a “square shaped wrist,” defined as the ratio of the wrist thickness to the wrist width >0.7. There appears to be a genetic susceptibility that is partially explained by the fact that many of the other risk factors are inherited.

Symptoms

Symptoms of CTS include paresthesia or aching in the distribution of the median nerve (palmar 3 ½ fingers). Patients may have difficulty localizing symptoms and often initially erroneously complain that their “whole hand is numb.” Pain may extend proximally to the elbow. The symptoms may begin nocturnally and progress from daytime activity-provoked to constant annoyance. Symptoms are aggravated by gripping activities, i.e. reading the paper, driving, or painting. Early on, symptoms may be relieved by “shaking the hands out.” In more severe cases, hand weakness or atrophy may be present. Patients may complain of “dropping things” or clumsiness, which may be more related to diminished sensory involvement, as opposed to a true motor deficit. Complaints of a tight/swollen feeling, skin color changes, or hand temperature changes have also been reported and may be related to compression of autonomic fibers within the median nerve. Symptoms may be recorded on a DASH or Boston Carpal Tunnel Questionnaire.

Evaluation

Clinical evaluation may reveal tenderness to palpation over the carpal tunnel. Any areas of hypertonicity in the cervical spine, scalene, pectoralis, pronator, and wrist flexor muscles should be noted. Wrist range of motion may not be limited, although sustained end range flexion or extension may reproduce complaints. Observe for joint restrictions in the cervical spine or wrist, especially the lunate. Clinicians may wish to measure the wrist for identification of a “square wrist sign.”

Orthopedic evaluation should attempt to reproduce symptoms via nerve compression tests. Tinel sign (tapping the carpal tunnel elicits symptoms in the median nerve distribution) is often positive. Phalen’s test (sustained full wrist flexion) is fairly specific for the diagnosis of CTS. Reverse Phalen’s test (sustained wrist extension) may cause symptoms from “traction ischemia.” Manual carpal compression (30 seconds of sustained compression of the carpal tunnel from an examiner’s thumb) has a reported sensitivity of 89% and specificity of 96% (11).

Neurologic evaluation of more chronic cases may demonstrate loss of two-point discrimination or pinprick over the first 3 ½ digits. Numbness involving the 5th digit or the dorsum of the hand should raise suspicion for neuropathy of alternate origin. Motor evaluation may reveal weakness of the median nerve-innervated (LOAF) muscles. The loaf muscles include the 1st and 2nd Lumbricales, Opponens pollicis, Abductor pollicic brevis, and Flexor pollicis brevis. LOAF muscle strength is evaluated via pinch grip. Observe for signs of thenar atrophy.

Double Crush Syndrome

CTS is sometimes part of a “double crush syndrome,” wherein the median nerve is sensitized to compression within the carpal tunnel as a result of more proximal axonal irritation (12). Common double crush partners for CTS include cervical arthropathy, cervical disc, TOS, and pronator syndrome. Clinicians should pay special attention to any potential sites of median nerve entrapment, including ligament of Struthers, lacertus fibrosis, inferior to the antecubital fossa between the two heads of the pronator teres muscle and the arch of the flexor digitorum. Failure to identify and treat additional sites of compression may result in ongoing symptoms. Patients presenting with bilateral hand symptoms should be presumed to have central cord involvement until disproven by MRI. (22)

Imaging

Plain film imaging of the wrist can help identify bony sources of compression but is rarely necessary. MRI is of limited help and used to identify cervical radiculopathy or soft tissue pathology at the wrist. Diagnostic ultrasonography is useful for demonstrating enlargement or fluid within the median nerve, as well adjacent soft tissue pathology. Although not generally necessary for mild cases, EMG/NCS is considered the diagnostic gold standard for identifying and objectively classifying the severity of CTS. (13). Electromyography is useful to evaluate specific muscle weakness, and nerve conduction studies can pinpoint more specific sites of nerve involvement.

The differential diagnosis of CTS includes cervical radiculopathy, pronator syndrome, TOS, compartment syndrome, diabetic or other neuropathy, lateral or medial epicondylitis, MS and Regional pain syndrome (RSD). Clinicians should consider local space-occupying lesions, including flexor tenosynovitis or ganglion cysts.

Conservative Management

If left untreated, CTS may result in permanent neurologic damage. The AAOS and the American Academy of Neurology recommend conservative management before considering surgical alternatives (14). A randomized clinical trial demonstrated that conservative manual therapy and surgery had similar effectiveness for improving self-reported function, symptom severity, and pinch-grip force on the symptomatic hand in a group of CTS patients. (29) Conservative management of CTS should focus on resolving any site of neurologic insult along the entire course of the median nerve.

Myofascial release may include STM or IASTM to the forearm, wrist, and hand, with a particular emphasis on the pronator teres, wrist flexors and carpal tunnel (15). Clinicians should be judicious in the application of pressure directly over the median nerve. Median nerve flossing has shown promise in treating CTS complaints (16). Manipulation of cervical or carpal restrictions (especially the navicular bone) has shown benefit. (17). Fifteen minutes of pulsed ultrasound daily has been shown to be an effective treatment option for CTS symptoms. The suggested settings are: frequency- 1 MHz, intensity-1w/cm2, duty cycle 25% (18, 21). Some studies have shown benefit for the use of low-level laser in the treatment of CTS. (28) Kinesiotape could be considered.

Stretching

Therapeutic and home stretching should be directed at hypertonicity in the cervical spine, scalene, pectoralis, pronator, and wrist flexor muscles. Additional home exercises should include chin retraction, carpal tunnel mobilization, median nerve glide & median nerve floss.

Home instructions may include selective rest to avoid repetitive wrist flexion or extension. Patients should avoid traditional push-ups and be cautious during intercourse to avoid trauma from sustained wrist flexion (19). Cycling will likely cause median nerve irritation and should be avoided. Splints that hold the wrist in a neutral or slightly extended position may reduce nocturnal symptoms (20). NSAIDs may help diminish swelling. Although the research is inconclusive, many studies suggest that taking 100-200mg of Vitamin B6 (pyridoxamine) daily may help relieve carpal tunnel symptoms. (18,23-26) One study demonstrated that 68% of patients taking 100mg of vitamin B6 twice per day experienced symptom alleviation (vs. 14% of the control group). (26) CTS patients should strive for aerobic fitness and maintain a healthy BMI.

Recalcitrant cases or patients with significant motor deficits may require consult for local steroid injections, oral steroids or surgical decompression. The Rand Corporation has created a detailed algorithm to help in determining the appropriateness of surgery for CTS patients. (27)

References

1. Papanicolaou GD, McCabe SJ, Firrell J. The prevalence and characteristics of nerve compression symptoms in the general population. J Hand Surg [Am] 2001;26:460-6.

2. Isam Atroshi, Christina Gummesson, Ragnar Johnsson, Ewald Ornstei, Jonas Ranstam, Ingmar Rosén, Prevalence of Carpal tunnel syndrome in a General Population. JAMA July 14, 1999, Vol 282, No. 2

3. Bland JD, Rudolfer SM. Clinical surveillance of carpal tunnel syndrome in two areas of the United Kingdom, 1991-2001. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003;74:1674-9

4. AAEM Quality Assurance Committee. Literature review of the usefulness of nerve conduction studies and electromyography for the evaluation of patients with carpal tunnel syndrome. Muscle Nerve 1993; 16: 1392-1414.

5. Stevens JC, Beard CM, O’Fallon WM, Kurland LT. Conditions associated with carpal tunnel syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc 1992;67(6):541–8

6. Garland FC, Garland CF, Doyle EJ Jr, et al. Carpal tunnel syndrome and occupation in U.S. Navy enlisted personnel. Arch Environ Health. Sep-Oct 1996;51(5):395-407

7. Kao SY. Carpal tunnel syndrome as an occupational disease. J Am Board Fam Pract. Nov-Dec 2003;16(6):533-42

8. Palmer KT, Harris EC, Coggon D. Carpal tunnel syndrome and its relation to occupation: a systematic literature review. Occup Med (Lond). Jan 2007;57(1):57-66

9. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Carpal Tunnel Fact Sheet updated March 1, 2013

10. D.I Clark, L.C Bainbridge, C Smith, R Hubbard Risk factors in carpal tunnel syndrome The Journal of Hand Surgery: British & European Volume 29, Issue 4, August 2004, Pages 315–320

11. Durkan JA. The carpal-compression test. An instrumented device for diagnosing carpal tunnel syndrome. Orthop Rev. Jun 1994;23(6):522-5.

12. Upton AR, McComas AJ. The double crush in nerve entrapment syndromes. Lancet 1973 Aug 18;2(7825):359-62.

13. Robinson LR. Electrodiagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. Nov 2007;18(4):733-46

14. American Academy of Neurology Practice parameter for carpal tunnel syndrome (summary statement) Neurology, 43 (1993), pp. 2406–2409

15. Burke J, Buchberger DJ, Carey-Loghmani MT, Dougherty PE, Greco DS, Dishman JD. A pilot study comparing two manual therapy interventions for carpal tunnel syndrome. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2007 Jan;30(1):50-61.

16. Horng YS, Hsieh SF, Tu YK, Lin MC, Horng YS, Wang JD. The comparative effectiveness of tendon and nerve gliding exercises in patients with carpal tunnel syndrome: a randomized trial. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2011;90:435-42

17. Page MJ, O’Connor D, Pitt V, Massy-Westropp N. Exercise and mobilisation interventions for carpal tunnel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Jun 13 2012;6:CD009899.

18. O’Connor D, Marshall S, Massy-Westropp N. Non-surgical treatment (other than steroid injection) for carpal tunnel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;(1):CD003219.

19. Zenian J. The role of sexual intercourse in the etiology of carpal tunnel syndrome

Medical Hypotheses 74 (2010) 950–952

20. Page MJ, Massy-Westropp N, O’Connor D, Pitt V. Splinting for carpal tunnel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Jul 11, 2012;7: CD010003.

21. Ebenbichler GR, Resch KL, Nicolakis P, et al. Ultrasound treatment for treating the carpal tunnel syndrome: randomised ‘‘sham’’ controlled trial. BMJ. 1998;316:731-735.

22. Kim HJ, Tetreault LA, Massicotte EM, Arnold PM, Skelly AC, Brodt ED, Riew KD. Differential diagnosis for cervical spondylotic myelopathy: literature review. Spine. 2013 Oct 15;38(22 Suppl 1): S78-88.

23. Aufiero E, Stitik TP, Foye PM, Chen B. Pyridoxine hydrochloride treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome: a review. Nutr Rev. 2004;62(3):96–104.

24. Bernstein AL, Dinesen JS. Brief communication: effect of pharmacologic doses of vitamin B6 on carpal tunnel syndrome, electroencephalographic results, and pain. J Am Coll Nutr. 1993;12:73–6.

25. Folkers K, Ellis J, Watanabe T, Saji S, Kaji M. Biochemical evidence for a deficiency of vitamin B6 in the carpal tunnel syndrome based on a crossover clinical study. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75(7):3410–2.

26. Kasdan M, Janes C. Carpal tunnel syndrome and vitamin B6. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;79:456–8.

27. Nuckols TK, Griffin A, et al. RAND/UCLA Quality-of-Care Measures for Carpal Tunnel Syndrome. Appendix VIII: Algorithm: Determining the Appropriateness of Surgery for Carpal Tunnel Syndrome. 2011 Rand Corporation

28. Shooshtari SM1, Badiee V, Taghizadeh SH, Nematollahi AH, Amanollahi AH, Grami MT. The effects of low-level laser in clinical outcome and neurophysiological results of carpal tunnel syndrome. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol. 2008 Jun-Jul;48(5):229-31.

29. Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Cleland J, Palacios-Ceña M, Fuensalida-Novo S, Pareja JA, Alonso-Blanco C. The Effectiveness of Manual Therapy Versus Surgery on Self-reported Function, Cervical Range of Motion, and Pinch Grip Force in Carpal Tunnel Syndrome: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 2017 Volume:47 Issue:3 Pages:151–161