MRI Appearance of Acetabular Labral Tears

The assessment of the acetabular labrum is a common reason for MR imaging of the hip. Most frequently, the study is ordered to rule out a labral tear. If a tear is present, it is important to identify it as this may be the source of the pain but may also lead to an onset of hip arthrosis or accelerate an existing arthrosis.

The most common symptom of a tear is general hip pain; however, it may include snapping and clicking sensations at the hip, joint locking or sharp pains associated with pivoting or twisting motions of the hip. A tear may exist in conjunction with acetabular dysplasia, slipped capital femoral epiphysis, femoro-acetabular impingement, or as an end stage phenomenon in degenerative hip disease.

Tears may span through a fairly broad age range, most commonly extending from the ages of 20 to 50 (1). In young athletes it may be associated with an acute traumatic event, and, in middle age, a femoro-acetabular impingement may be a common cause. Older patients may experience a tear as a result of degenerative change in the labrum, with subsequent development of an actual rent in the fibers that extends to the outer surface of the tissue. A cyst may form at the site of a labral tear. This will appear as a well-defined hyperintense collection of signal adjacent to the labrum.

Tears are graded along a scale that extends from hyperintense signal within the labrum, but without extension to the surface, to complete labral detachment.

MRI remains the best imaging modality for the diagnosis of labral tear. A greater degree of diagnostic accuracy is afforded with the administration of intra-articular contrast in the study. The contrast may fill in the site of tear and make it more obvious. A normal healthy labrum manifests low signal intensity (black) on all imaging sequences. Tears are most often seen on the coronal images with fat suppression and are most commonly located in antero-superior or postero-superior sections of the labrum. They appear as hyperintense (white) signal on the fat suppressed images.

Figure 1 demonstrates an intermediate signal intensity zone (white arrow) within the labrum. This represents an area of degenerative labrum adjacent to an osteophyte that is forming at the lateral aspect of the acetabulum.

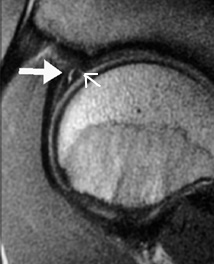

Contrast the appearance of the degenerative labrum in figure 1 with the image of a true tear in figure 2. The signal in the tear is higher than in the degenerative labrum and extends to the articular surface of the labrum. Figure 3 also represents a labral tear; note the high signal within the low signal intensity labrum (large white arrow). This tear does not extend to the articular surface. There is a thin zone of undercutting cartilage at the attachment of the labrum to the acetabulum (thin white arrow). Cartilage undercutting is a normal finding and should not be confused with a tear.

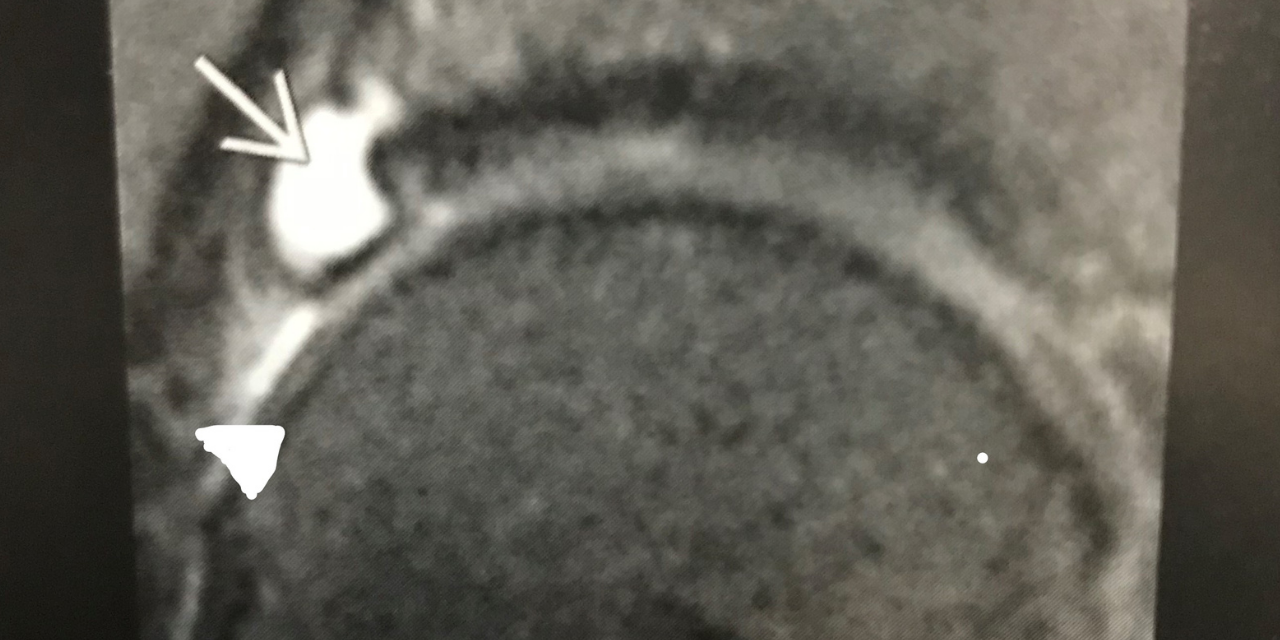

In some cases, there may be complete detachment of the labrum, with the development of an adjacent paralabral cyst. This is demonstrated in figure 4. The white arrow points to the hyperintense fluid filled paralabral cyst. The apex of the white triangle points to the detached degenerative labrum that appears as intermediate mixed signal and is displaced away from the acetabulum.

Labral tears are typically progressive. Conservative treatment consists of activity modification, particularly with limitation of hip flexion and internal rotation, movements that may directly impact the tear. Chiropractic manipulation to address joint dysfunction in the remainder of the lower extremity my help to effect normal hip movement and reduce undue stress on the labrum. Soft tissue manipulation and physiotherapy modalities may be palliative and be of benefit in temporal alleviation of pain.

Cases recalcitrant to these conservative measures may benefit from anti-inflammatory medication and possibly intra-articular steroid injection in acute flare-ups of pain. Surgical debridement may be a last resort in some cases.

1. Stoller D. W.: Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine, ed 2. Philadelphia, J. B. Lippincott Company 1993.