Bronchogenic Carcinoma on Thoracic Spine Study

The following case study involves a very common x-ray series. Thoracic spine x-rays are routinely ordered, and the radiographic technique employed can vary from one clinic to another. The major difference usually lies in the degree to which the lung fields are imaged, and, to a lesser extent, the degree of cervical spine that is imaged. Some doctors like to include as much of the lung fields as possible, ostensibly to function also as chest film, without taking a separate PA chest projection.

I can understand the rationale for this from economic and imaging time standpoints, although there are some drawbacks when using thoracic spine technique to visualize the chest. Specifically, the kVp used for thoracic spine (80) and chest (120) is markedly different. The higher chest kVp produces a longer scale of contrast, which is better for lung soft tissue, while the thoracic spine kVp produces better overall contrast for bone. Another problem lies in the magnification of the heart shadow on an AP projection. Magnification is decreased with the AP technique. Sometimes, however, a lung lesion may be identified on a thoracic spine study when widely collimated, even if a PA chest is not included in the study. The following case demonstrates this.

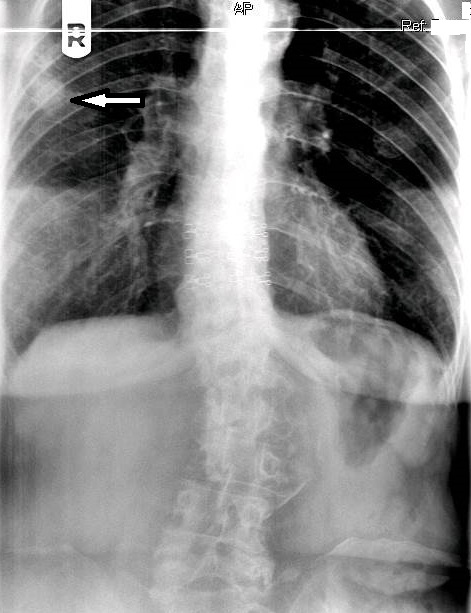

This 60-year-old female presented with a general complaint of back pain. She is a heavy smoker and has lost approximately 20 pounds over the past year. A thoracic spine x-ray study consisting or AP and lateral views was performed and sent out for interpretation.

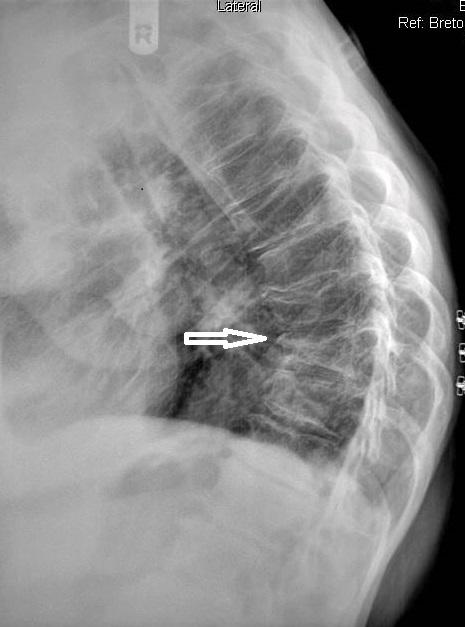

On figure 1, the original AP thoracic projection, an oval density is seen in the periphery of the right lung field (white arrow points to lesion). A thoracic and lumbar scoliosis is also seen. The lateral projection revealed multilevel degenerative change, as well as compression fractures at T9 and T10, with a focal kyphotic deformity seen in figure 2. Since a PA chest projection was not included, a chest series consisting of PA and lateral views was suggested to better evaluate the suspected lesion.

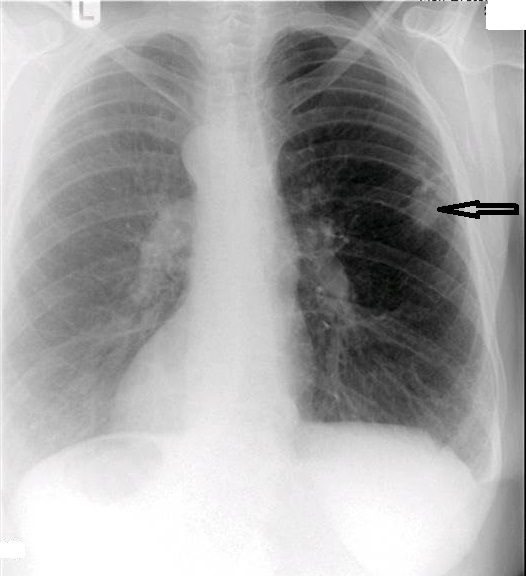

The chest series was obtained and again demonstrated the lesion noted previously on the thoracic spine. The lesion is more clearly seen on figure 3, the PA chest projection. It measured 3.0 cm in the long axis, and the border was not particularly sharp and appeared somewhat spiculated on close inspection (open arrow points to lesion). No calcifications were noted within the lesion. This finding is worrisome, as benign granulomatous lesions, which are often discovered incidentally, frequently manifest some degree of calcification, while more aggressive lesions exhibit calcification less often. Figure 4 again demonstrates the thoracic spine compression fractures.

It was recommended that the patient undergo a chest CT examination in order to more thoroughly investigate the lesion and also be referred to an oncologist or internal medicine physician for follow-up. A chest CT was performed and identified the mass in the right lung. A spiculated border was noted. The lack of any internal calcification within the lesion was confirmed. No definite lymphadenopathy was identified on the CT. The patient was then scheduled for lesion biopsy. The subsequent biopsy revealed that the mass was malignant. This patient is currently awaiting the results of additional testing before treatment options are discussed.

Plain film is far from the most sensitive imaging modality when detecting small intrapulmonary lesions, and CT remains the gold standard for advanced imaging of the chest. It allows the identification of specific diagnostic features and also permits evaluation of the entire thorax (1). As you can readily see from the submitted images, the appearance of the thoracic spine study varies markedly from the chest study when examining the soft tissues of the chest. Although not considered a reliable projection for chest evaluation, the AP thoracic view may reveal findings not related to the thoracic spine. Ideally, a PA chest projection should be included as part of a thoracic spine study. As in any study, a thorough search must be made of all the visible tissue. If an abnormality is noted, the appropriate recommendation or referral needs to be made.

References:

- European Respiratory Journal; April 1, 2002, vol. 19, no. 4 722-742