Plantar Fasciitis

The plantar fascia is a dense, fibrous band serving as a biomechanical stabilizer, as well as a protector to the vulnerable neurovascular structures on the plantar aspect of the foot. The diagnosis “plantar fasciitis” encompasses disorders ranging from acute inflammation to chronic fibrotic degeneration, usually involving the calcaneal attachment. (1,2) Plantar fasciitis most commonly affects the medial portion of the band. (2)

The band’s proximal origin is the medial calcaneal tubercle, and its distal attachments are all five toes. The band functions, via the “windlass mechanism” to stabilize the foot during gait; i.e., at heel strike, the plantar fascia is slack to allow the foot to accommodate uneven surfaces. As the heel lifts and forefoot dorsiflexes toward toe off, the distal plantar fascia “winds” up and around the first MTP joint, pulling the plantar fascia taut, shortening the distance between the heel and forefoot, raising the arch and creating a stiffer lever for propulsion. (3)

Plantar Fasciitis

Although the term, “plantar fasciitis” implies inflammation, more recent studies suggest that plantar fascia pain results from a non-inflammatory, degenerative process. (4-12) Initial insults may generate an acute inflammatory reaction, but repetitive chronic overload results in a breakdown of the inflammatory process and a disorganized healing process that fails to regenerate “normal” tissue.

Plantar fasciitis is the most common cause of plantar heel pain, affecting approximately 10% of the population. (14-18) The condition is present bilaterally in 20-30% of those affected. (19) The condition is common in young runners and middle-aged women, but the majority of plantar fascia patients are over the age of 40. (16-18)

Causes

Like most cumulative trauma disorders, the etiology of plantar fasciitis is multi-factoral. (21) Problems typically arise when repetitive eccentric strain exceeds the tissue’s threshold for injury. Certain factors may increase the likelihood of developing the disorder. The leading biomechanical cause for plantar fasciitis is pes planus (fallen arch) which increases tension on the plantar fascia, leading to repetitive micro-trauma at the band’s vulnerable attachment on the medial calcaneus. (22) Patients with pes cavus are likewise predisposed since a cavus foot is relatively immobile, and forces that would generally be dissipated by bony structures are now absorbed by the plantar fascia. (16,25)

Tightness or weakness in the gastroc and soleus directly contribute to plantar fasciitis by increasing tensile strain on the plantar fascia. (25-27) Gastroc and soleus hypertonicity limits dorsiflexion, meaning the plantar fascia must accommodate for this lost motion. (28) Gastroc and soleus weakness limits propulsion and increases loads on the plantar fascia and the intrinsic muscles of the foot. (28)

Hamstring

Patients with plantar fasciitis are almost 9 times more likely to demonstrate hamstring hypertonicity. (29) Hamstring tightness may induce prolonged forefoot loading and increase strain to the plantar fascia. (30) Rapid weight gain and obesity are also recognized as contributors to plantar fasciitis. (17,25) Patients with BMIs greater than 35 are approximately 2.5 times more likely to experience plantar fasciitis, as compared to those with BMIs less than 35. (29)

Patients may be predisposed by occupations or activities that involve prolonged ambulation, including teachers, construction workers, cooks, nurses, distance runners, etc. Runners average 1200 steps per mile at a 6-minute per mile pace, and walkers average 2300 steps at a 20-minute/mile pace. The plantar fascia must absorb up to seven times body weight during the push-off phase of running and biomechanical deficits are quickly amplified. Patients often present following an increase in training demand or change in running surface, such as concrete. (25)

Complaints

The most common presenting complaint of plantar fasciitis is a sharp pain with the first couple of steps in the morning or following any period of prolonged inactivity. (16,25) Symptoms are often noted during the push-off phase when the band is at peak tension. (32) Symptoms are amplified by prolonged weight bearing, especially when compounded by inadequate foot support or walking barefoot. (25) Walking upstairs and sprinting or forefoot running tends to exacerbate symptoms by increasing plantar fascia strain. Patients report relief when unloading the foot by sitting or lying down. Symptomatic episodes are more frequent following periods of inactivity late in the day.

Testing

Palpation will likely reveal tenderness at the medial calcaneal tubercle. (33) Some patients note tenderness to palpation in the mid portion of the plantar arch. (33) Palpation may demonstrate plantar fascia tightness with palpable bands of tenderness or adhesion. Tenderness to palpation is often exacerbated by simultaneously dorsiflexing the great toe to 65 degrees. (34) The Windlass test for plantar fasciitis is the reproduction of heel pain during passive dorsiflexion of the toes. Performing this test while the patient is standing/weight bearing more than doubles sensitivity to almost 33%. (35)

Clinicians should palpate the posterior aspect of the calcaneus to assess for alternate sources of pain (i.e. Sever’s disease, retrocalcaneal bursitis, Achilles tendinopathy, stress fracture, etc.) The heel squeeze test may help identify a stress fracture. Asking the patient to walk on his or her toes may provide additional information, as patients with plantar fasciitis report discomfort when shifting weight onto their toes, while patients with stress fractures or heel spurs find relief in that position. (36) Patients with stress fractures of symptomatic heel spurs may note pain at heel strike. (32)

Range of motion may demonstrate limited ankle dorsiflexion due to Achilles or gastroc hypertonicity. Clinicians should assess for hamstring tightness, as well as the strength of the posterior tibialis and flexor digitorum brevis. The flexor digitorum brevis works in concert with the plantar fascia by contracting to divert strain away from the overworked fascia. (37) The flexor digitorum brevis may be assessed via the “Paper grip test” (the seated patient stands with the second through fifth digits on a business card, while the clinician attempts to pull the card from beneath the patient’s toes.) (38)

Clinicians should assess for biomechanical deficiencies, including leg length discrepancy, pes cavus, hyperpronation, or pes planus. (33) Clinicians may assess the patient’s arch with hyperpronation cluster tests. Evaluation of shoe insoles may help to determine flexor digitorum brevis strength. Runners with strong flexor digitorum brevis muscles will demonstrate indents beneath their middle toes. (36)

Red Flags

Peripheral neuropathies, including tarsal tunnel syndrome and Baxter’s neuritis, sometimes masquerade as plantar fasciitis. Baxter’s neuritis is an often-overlooked cause of heel pain and may account for up to 20% of all heel pain. Baxter’s neuritis is compression of the inferior calcaneal nerve, resulting in weakness of the abductor digiti minimi. (39) Entrapment may result in pain that is indistinguishable from plantar fasciitis and a subtle loss of fifth digit abduction. (40-46) The pain of Baxter’s neuritis may be provoked by abducting and dorsiflexing the forefoot for 30-60 seconds. (2,96) Tarsal tunnel syndrome is compression of the posterior tibial nerve, as it passes through the tarsal tunnel, resulting in pain and/or paresthesia radiating into the plantar arch and heel. Tarsal tunnel syndrome may be identified by a positive Tinel sign and a Dorsiflexion-eversion test.

Any patient with bilateral plantar fasciitis should be carefully screened for the presence of inflammatory arthropathy. (48) Some reports indicate that 16% of subcalcaneal heel pain patients will later be diagnosed with a systemic disease, such as RA, Beckets, AS, SLR, Reiters, psoriatic arthritis, diabetes, or gout. (49) Early signs of inflammatory arthropathy are similar to those of plantar fasciitis with the exception of symptoms that tend to occur bilaterally with more pronounced swelling. (2)

Additional differential considerations for plantar fasciitis include contusion, Sever’s disease, stress fracture, peripheral neuropathy, fat pad syndrome, infection, neoplasm, inflammatory arthropathy, neuropathic pain, Padgett’s disease, S1 radiculopathy, and tendinitis/tendinopathy.

Radiology

Radiographs are typically not required for the diagnosis of plantar fasciitis. (51) Radiographs may, however, be useful in differentiating plantar fasciitis from other diagnoses, including neoplasm or fracture. A calcaneal stress fracture may appear on standard radiography as a radiopaque band traversing the trabecular pattern in the posterior calcaneus. Plain film radiographs commonly expose plantar calcaneal enthesopathy (heel spurs). Studies demonstrate no correlation between spur size and the patient’s subjective complaints. (52) Calcaneal enthesophytes are considered coincidental and irrelevant radiographic findings. (53) They are a sequela rather than a cause of the process. (54,55) Spurs are thought to develop when long-standing tension creates a traction apophysitis, via Wolf’s Law. The presence of a heel spur suggests abnormal stress in the region for at least six months. (56) Heel spurs are present in approximately 50% of symptomatic patients and 15-20% of asymptomatic patients. (54,57) Studies now suggest that heel spurs develop at the origin of the flexor digitorum brevis muscle, as opposed to the plantar fascia attachment. (58)

Bone scans may be useful to rule out calcaneal stress fracture or neoplasm, although they will not differentiate between the two. Advanced imaging, including MRI, may be appropriate for recalcitrant cases or to rule out differential diagnostic considerations, including Baxter’s neuritis. Sonographic studies demonstrate that while the average plantar fascia is approximately 2 mm thick, patients with plantar fasciitis symptoms demonstrate a degenerative thickening of 4 mm or greater. (59) Diagnostic ultrasound evidence of decreasing plantar fascia thickness is associated with improvement. (60)

Treatment

Eighty to ninety percent of plantar fasciitis patients who forego treatment will report the resolution of their complaints within 18 months. Conservative treatment, including manual therapy, stretching, myofascial release, exercise, orthotics, physical therapy modalities, and night splints may improve results. (61-63) The best treatment outcomes are achieved by combining multiple techniques- particularly mobilization and exercise. (63,97)

Patients may need to temporarily limit activities that exacerbate symptoms, including jumping, running, and sprinting. Once patients find a tolerable level of activity, they should not increase their training intensity by more than 10% per week. (64) Runners should avoid running hills, and toe or forefoot runners may need to temporarily alter their running form. Runners may benefit by reducing stride length and increasing cadence. (36) Running shoes lose half of their shock absorption capacity after 300-500 miles and should be replaced within that range. (65,88,89) Safer alternatives to running include swimming, bicycling, and elliptical machines. (66)

Patients who hyperpronate and those with fallen arches will benefit from arch supports or orthotics. (67) The use of a Tensoplast wrap or commercial elastic wrap (PSC fabrifoam) will help support fallen arches. Low dye taping is effective in limiting pronation. (68) A medial heel wedge forces the foot into a varus posture and significantly reduces plantar fascia strain. (69) Patients with true hypersensitivity to pressure may benefit from a viscoelastic heel cup or small cushion donut over the medial calcaneal tubercle. (70) The use of elastic therapeutic tape has been proposed for the treatment of plantar fasciitis.

Immobilization

Immobilizing tissue in a lengthened state speeds recovery. (71) Chronic plantar fasciitis patients may benefit from using a boot or night splint (Strassburg sock), which limits passive plantar flexion and allows the plantar fascia to “heal” in a lengthened state. (92,93) Patients should be counseled on proper shoe wear. Patients with low arches may benefit from “motion control” shoes. Runners with average arches should choose “neutral” or “stability” shoes. (72) Patients with high arches may benefit from a “cushioned” shoe. (73)

Since most chronic cases of plantar fasciitis do not show histologic evidence of inflammation, the benefit of “anti-inflammatory” modalities is questionable. (74) Some patients report at least palliative relief by using NSAIDs, ice, and modalities. Low-level laser therapy may be useful for the treatment of chronic plantar fasciitis. (75)

Ankle joint mobilization and manipulation can help restore normal motion, particularly dorsiflexion. (76,77,90) The addition of gastroc/ soleus and plantar fascia trigger point massage and soft tissue manipulation to traditional treatment programs produces superior short-term outcomes. (62) Myofascial release procedures, including transverse friction massage and IASTM, are effective tools that may stimulate fibroblast proliferation and plantar fascia regeneration. (79,80,95) IASTM may be performed in a fanning fashion over the length of the plantar fascia in a strumming fashion near the medial calcaneal origin.

Stretching Exercises

Stretching exercises are appropriate for the gastroc, soleus, hamstring, and plantar fascia. (81,91) The plantar fascia may be effectively stretched by sitting in a Figure 4 position, and fully dorsiflexing the great toe for 10 seconds repetitively throughout the day. Routinely stretching the plantar fascia in this fashion is associated with significantly improved outcomes. (81) Plantar fascia mobilization may be performed at home by rolling a golf ball or frozen water bottle beneath the plantar fascia. The use of a Prostretch may assist in stretching and mobilizing the plantar flexors.

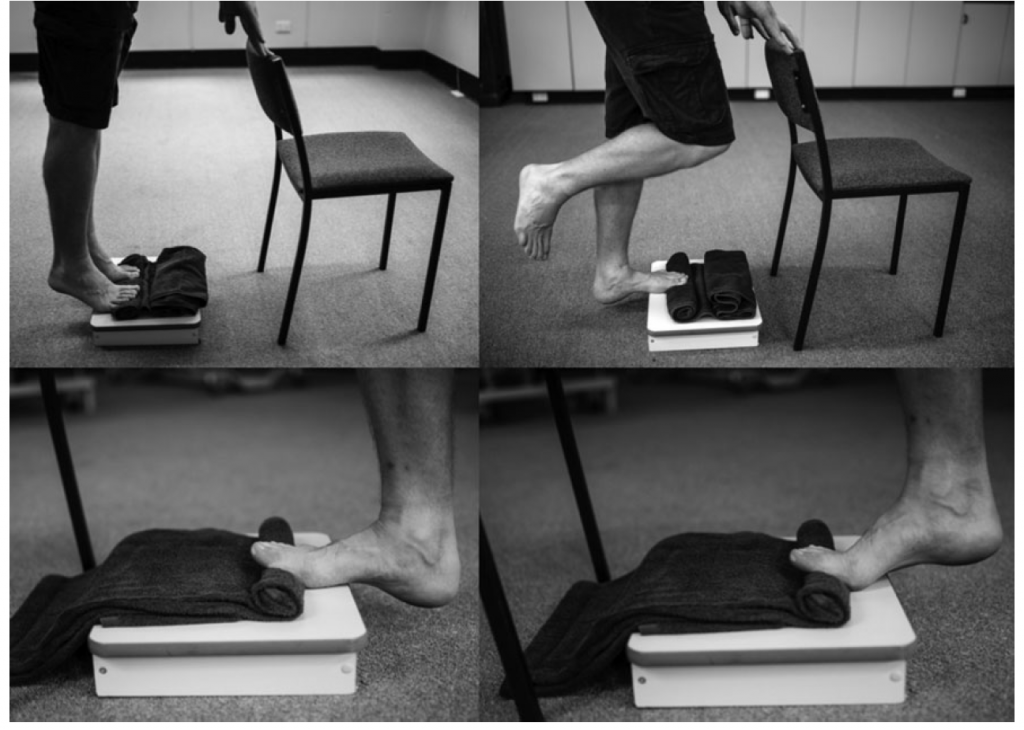

Strengthening exercises are appropriate for the gastroc, soleus, posterior tibialis, and intrinsic muscles of the foot. (82) Examples include marble and towel gripping exercises. Strengthening exercises for the posterior tibialis should be implemented to help arch support. Strengthening of the flexor digitorum brevis is an important component of treatment and may be accomplished by performing toe flexion with an exercise band. (36) Eccentric heel raises with the great toe positioned in passive dorsiflexion (i.e. great toe propped up with a towel) have shown benefit for plantar fasciitis patients. (98)

Nearly two-thirds of foot and ankle orthopedic specialists prefer stretching and manual therapy over anti-inflammatories or corticoid steroid injections for chronic plantar fasciitis patients. (83) Medical management of recalcitrant plantar fasciitis includes extracorporeal shock-wave therapy (ESWT), cortisone injections, and surgery. ESWT has shown to help some patients. (63,85) ESWT (originally developed as lithotripsy) is thought to break up calcific deposits and stimulate fibroblast activity to encourage healing. Corticoid steroids may provide an anti-inflammatory effect in cases where inflammation is present, but carry the risk of spontaneous plantar fascia rupture or damage to the heel pad. (62,87) Surgical management includes fasciotomy.

References

1. Kendrick Alan Whitney Plantar Fasciosis Copyright 2010-2013 Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp accessed 4/16/14

2. Thomas Michaud, Differential Diagnosis of Heel Pain Dynamic Chiropractic – January 15, 2013, Vol. 31, Issue 02

3. Michaud T. Foot Orthoses and Other Forms of Conservative Foot Care. 1st ed. Newton, MA: Thomas C Michaud; 1997.

4. Martin J, Hosch J, Goforth WP, Murff R, Lynch DM, Odom R. Mechanical Treatment of Plantar Fasciitis. Journal of the American Podiatric Association 2001; 91(2):55-62.

5. Aldridge T. Diagnosing Heel Pain in Adults. American Family Physician 2004; 70(2):332-8.

6. Fillipou D, Kalliakmanis A, Triga A, Rizos A, Grigoriadis E. Sport-Related Plantar Fasciitis. Current Diagnostic and Therapeutic Advances. Folia Medica 2004; 46(3):56-60.

7. Wearing S, Smeathers J, Yates B, Sullivan P, Urry S, Dubois P. Sagittal Movement of the Medial Longitudinal Arch is Unchanged in plantar fasciitis. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2004; 36(10):1761-67.

8. Lemont H, Ammirati K, Usen N. Plantar Fasciitis: A Degenerative Process Without Inflammation. Journal of the American Podiatric Association 2003; 93(3):234-37.

9. Huang YC, Wang LY, Wang HC, Chang KL, Leong CP. The Relationship Between the Flexible Flatfoot and Plantar Fasciitis: Ultrasonographic Evaluation. Chang Gung Medical Journal 2004; 27(6):443-8.

10. Dyck D, Boyajian-O’Neill L. Plantar Fasciitis. Clinical Journal of Sports Medicine 2004; 14(5):305-309.

11. Cole C, Seto C, Gazewood J. Plantar Fasciitis: Evidence-Based Review of Diagnosis and Therapy. American Family Physician 2005; 72(11):2237-42.

12. Roxas M. Plantar Fasciitis: diagnosis and therapeutic considerations. Alternative Medicine Review 2005; 10(2):83-93.

14. DeMaio M, Paine R, Mangine RE, Drez DJr. Plantar fasciitis. Orthopedics 1993; 16:1153-1163.

15. Neufeld SK. Plantar Fasciitis: Evaluation and Treatment J Am Acad Orthop Surg June 2008 vol. 16 no. 6 338-346

16. Singh D, Angel J, Bentley G, Trevino SG. Fortnightly review. plantar fasciitis.

BMJ. 1997;315:172-175.

17. DeMaio M, Paine R, Mangine RE, Drez D,Jr. Plantar fasciitis. Orthopedics. 1993;16:1153-1163.

18. Barrett SJ, O’Malley R. Plantar fasciitis and other causes of heel pain. Am Fam Physician. 1999;59:2200-2206.

19. Charles LM. Plantar fasciitis. Lippincotts Prim Care Pract. 1999;3:404-407

21. Gross MT, Byers JM, Krafft JL, Lackey EJ, Melton KM. The impact of custom semirigid foot orthotics on pain and disability for individuals with plantar fasciitis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2002;32:149-157.

22. Abreu M, Chung C, Mendes L, et al. Plantar calcaneal enthesophytes: new observations regarding sites of origin based on radiographic, MR imaging, anatomic, and paleopathologic analysis. Skeletal Radiol. 2003;32:13-21.

25. Young CC, Rutherford DS, Niedfeldt MW. Treatment of plantar fasciitis. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:467-74, 477-8.

26. Schepsis AA, Leach RE, Gorzyca J. Plantar fasciitis. etiology, treatment, surgical results, and review of the literature. Clin Orthop. 1991;(266):185-196.

27. Bolivar YA, Munuera PV, Padillo JP. Relationship between tightness of the posterior muscles of the lower limb and plantar fasciitis. Foot Ankle Int. Jan 2013;34(1):42-8.

28. Bedi HS, Love BR. Differences in impulse distribution in patients with plantar fasciitis. Foot Ankle Int. 1998;19:153-156.

29. Labovitz JM, Yu J, Kim C. The role of hamstring tightness in plantar fasciitis. Foot Ankle Spec. 2011 Jun;4(3):141-4.

30. (Harty J, Soffe K, O’Toole G, and Stevens NM. The role of hamstring tightness in plantar fasciitis. Foot, ankle, int. 2005, December; 26 (12): 1089-92)

32. Michaud T, New Techniques For Treating Plantar Fasciitis Competitor Group Published Mar. 6, 2014

33. Boberg J, Dauphinee D. Plantar Heel. In: Banks AM, Downey D, Martin S, Miller. McGlamry’s Comprehensive Textbook of Foot and Ankle Surgery. 1. 3. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001:471.

34. DeGarceau D, Dean D, Requejo SM, Thordarson DB. The association between plantar fasciitis and Windlass test results. Foot & Ankle International 2004; 25(9):687-8

35. De Garceau D, Dean D, Requejo SM, Thordarson DB. The association between diagnosis of plantar fasciitis and Windlass test results. Foot Ankle Int. Mar 2003;24(3):251-5.

36. Michaud T, New Techniques For Treating Plantar Fasciitis Competitor Group Published Mar. 6, 2014

37. Wearing S, Smeathers J, Yates B, et al. Sagittal movement of the medial longitudinal arch is unchanged in plantar fasciitis. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36:1761- 1767.

38. Menz H, Zammit G, Munteanu S, Scott G. Plantarflexion strength of the toes: age and gender differences and evaluation of a clinical screening test. Foot Ankle Int. 2006; 27:1103-1108.

39. Dirim B, Resnick D, Ozenler, N.K. Bilateral Baxter’s Neuropathy secondary to plantar fasciitis, Med Sci Monitor, 2010 April; 16 (4): CS 50-53.)

40. Delfaut EM, Demondion X, Bieganski A, Thiron MC, Mestdagh H, Cotten A. Imaging of foot and ankle nerve entrapment syndromes: from well-demonstrated to unfamiliar sites. Radiographics. 2003; 23:613-623.

41. Oztuna V, Ozge A, Eskandari MM, Colak M, Golpinar A, Kuyurtar F. Nerve entrapment in painful heel syndrome. Foot Ankle Int 2002; 23: 208-211.

42. Chundru U, Liebeskind A, Seidelmann F, Fogel J, Franklin P, Beltran J. Plantar fasciitis and calcaneal spur formation are associated with abductor digiti minimi atrophy on MRI of the foot. Skeletal Radiol. 2008; 37:505-10.

43. Donovan A, Rosenberg ZS, Cavalcanti CF. MR imaging of entrapment neuropathies of the lower extremity. Part 2. The knee, leg, ankle, and foot. Radiographics. 2010; 30:1001-1019.

45. Baxter DE. Release of the nerve to the abductor digiti minimi. In: Kitaoka HB, ed. Master techniques in orthopaedic surgery of the foot and ankle. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2002: 359.

46. Lui, TH. Endoscopic decompression of the first branch of the lateral plantar nerve. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2007; 127:859-61.

48. Charles LM. Plantar fasciitis. Lippincotts Prim Care Pract. 1999;3:404-407.

49. Thordarson DB. The Foot and Ankle. 2004 Lippincott Williams and Wilkins p. 190

51. McMillan AM, Landorf KB, Barrett JT, Menz HB, Bird AR. Diagnostic imaging for chronic plantar heel pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Foot Ankle Res. Nov 13 2009;2:32.

52. Gulick DT, Bouton K, Detering K, Racioppi E, Shafferman M. Effects of acetic acid iontophoresis on heel spur reabsorption. Phys Ther Case Rep. 2000;3:64-70.

53. Banks AS, Downey MS, Martin DE, Miller SJ. Foot and Ankle Surgery. Philadelphia: Lipincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001

54. Barrett SL, Day SV, Pignetti TT, Egly BR. Endoscopic heel anatomy: analysis of 200 fresh frozen specimens. J Foot Ankle Surg. Jan-Feb 1995;34(1):51-6

55. Saidoff D, McDonough AL. Medial calcaneal heel pain upon weight bearing in an intrinsic foot deformity. In: Critical Pathways in Therapeutic Interventions – Extremities and Spines. 1st ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2002:319-338.

56. The diagnosis and treatment of heel pain. J Foot Ankle Surg. Sep-Oct 2001;40(5):329-40.

57. Tisdel CL, Donley BG, Sferra JJ. Diagnosing and treating plantar fasciitis: A conservative approach to plantar heel pain. Cleve Clin J Med. 1999;66:231-235.

58. Abreu M, Chung C, Mendes L, et al. Plantar calcaneal enthesophytes: new observations regarding sites of origin based on radiographic, MR imaging, anatomic, and paleopathologic analysis. Skeletal Radiol. 2003;32:13-21.

59. Dubin J. Evidence-Based Treatment for Plantar Fasciitis: Review of the Literature. March 2007 www.dubinchiro.com/plantar.pdf accessed 5/1/14

60. Mahowald S, Legge BS, Grady JF. The correlation between plantar fascia thickness and symptoms of plantar fasciitis. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. Sep 2011;101(5):385-9.

61. Buchbinder R. Clinical practice. plantar fasciitis. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2159-2166.

62. Renan-Ordine R, Alburquerque-Sendin F, Rodrigues De Souza D, et al. Effectiveness of myofascial trigger point manual therapy combined with a self-stretching protocol for the management of plantar heel pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2011;41:43.

63. Díaz López AM, Guzmán Carrasco P. Effectiveness of different physical therapy in conservative treatment of plantar fasciitis: systematic review. Rev Esp Salud Publica. 2014 Feb;88(1):157-78.

64. Quillen WS, Magee DJ, Zachazewski JE. The process of athletic injury and rehabilitation. Athletic Injuries and Rehabilitation. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Co; 1996:3-8.

65. Messier SP, Edwards DG, Martin DF, et al. Etiology of Iliotibial Band Friction Syndrome in Distance Runners. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 1995; 27(7):951-60.

66. Dyck D, Boyajian-O’Neill L. Plantar Fasciitis. Clinical Journal of Sports Medicine 2004; 14(5):305-309.

67. Landorf K, Keenan A, Herbert R. Effectiveness of Different Types of Foot Orthoses for the Treatment of Plantar Fasciitis. Journal of the American Podiatric Association 2004; 94(6):542-49.

68. Radford J, Burns J, Buchbinder R, Landorf K, Cook C. The Effect of Low-Dye Taping on Kinematic, Kinetic, and Electromyographic Variables. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 2006; 36(4):232-41.

69. Kogler G, Veer F, Solomonidis S, Paul J. The influence of medial and lateral placement of orthotic wedges on loading of the plantar aponeurosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:1403-13.

70. Sobel E, Levitz S, Caselli M. Orthoses in the Treatment of Rearfoot Problems. Journal of the American Podiatric Association 1999; 89(5):220-33.

71. DiGiovanni B, Nawoczenski D, Lintal M, et al. Tissue-specific plantar fascia-stretching exercise enhances outcomes in patients with chronic heel pain. A prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg. 2003;85-A:1270–1277.

72. Butler R, Davis I, Hamill J. Interaction of Joint Type and Footwear on Running Mechanics. The American Journal of Sports Medicine 2006; 34(12):1998-2005.

73. Michaud T. Arch Height and Running Shoes: The Best Advice to Give Patients. Dynamic Chiropractic Vol 32(9) May 2014

74. Roxas M. Plantar Fasciitis: diagnosis and therapeutic considerations. Alternative Medicine Review 2005; 10(2):83-93.

75. Jastifer JR1, Catena F, Doty JF, Stevens F, Coughlin MJ. Low-Level Laser Therapy for the Treatment of Chronic Plantar Fasciitis: A Prospective Study. Foot Ankle Int. 2014 Feb 7

76. Young B, Walker M, Strunce J, Boyles R. A Combined Treatment Approach Emphasizing Impairment-Based Manual Physical Therapy for Plantar Heel Pain: A Case Series. The Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 2004; 34(11):725-33.

77. Hyde T. Conservative Management of Sports Injury. Baltimore:Williams & Wilkins, 1997; pp 477-82

79. Martin J, Hosch J, Goforth WP, Murff R, Lynch DM, Odom R. Mechanical Treatment of Plantar Fasciitis. Journal of the American Podiatric Association 2001; 91(2):55-62.

80. Brosseau L, Casimiro, Milne S, et al. Deep Transverse Friction Massage for Treating Tendinitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002; (4):CD003528

81. Didiovanni B, Nawoczenski D, Lintal M, Moore E, Murray J, Wilding G, Baumhauer J. Tissue-Specific Plantar Fascia-Stretching Exercise Enhances Outcomes in Patients with Chronic Heel Pain: A Prospective, Randomized Study. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery 2003; 85-A(7):1270-77

82. Allen RH, Gross MT. Toe Flexors Strength and Passive Extension Range of Motion of the First Metatarsophalangeal Joint in Individuals with Plantar Fasciitis. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 2003; 33(8): 468-78.

83. DiGiovanni BF, Moore AM, Zlotnicki JP, Pinney SJ. Preferred management of recalcitrant plantar fasciitis among orthopaedic foot and ankle surgeons. Foot Ankle Int. 2012 Jun;33(6):507–12.

85. Yin MC1, Ye J, Yao M, Cui XJ, Xia Y, Shen QX, Tong ZY, Wu XQ, Ma JM, Mo W. Is extracorporeal shock wave therapy clinically efficacy for relief of chronic, recalcitrant plantar fasciitis? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo or active-treatment controlled trials. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014 Mar 21.

87. Acevedo JI, Beskin JL. Complications of plantar fascia rupture associated with corticosteroid injection. Foot Ankle Int. Feb 1998;19(2):91-7

88. Reid DC. Sports Injury Assessment and Rehabilitation. New York: Churchill Livingston, 1992.

89. Messier SP, Edwards DG, Martin DF, et al. Etiology of Iliotibial Band Friction Syndrome in Distance Runners. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 1995; 27(7):951-60.

90. Dimou ES, Brantingham JW, Wood T. A randomized controlled trial (with blinded observer) of chiropractic manipulation and Achilles stretching vs. orthotics for the treatment of plantar fasciitis. J Am Chiro Assoc. 2004;41(9):32–42.

91. Pfeffer G, et al. Comparison of custom and prefabricated orthoses in the initial treatment of proximal plantar fasciitis. Foot Ankle Int. 1999;20(4):214–221

92. Batt ME, Tanji JL, Skattum N. Plantar fasciitis: a prospective randomized clinical trial of the tension night splint. Clin J Sports Med. 1996;6(3):158–162

93. Powell M, Post WR, Keener J, Wearden S. Effective treatment of chronic plantar fasciitis with dorsiflexion night splints: a crossover prospective randomized outcome study. Foot Ankle Int. 1998;19(1):10–18.

94. Flatt DW. Common Diagnoses and Treatments Affecting the Lower Limbs. Presentation at the 2015 American College of Chiropractic Orthopedists Convention. Las Vega,s NV April 24, 2015.

95. Piper S, Shearer HM, Côté P, Wong JJ, Yu H, Varatharajan S, Southerst D, Randhawa KA, Sutton DA, Stupar M, Nordin MC, Mior SA, van der Velde GM, Taylor-Vaisey AL. The effectiveness of soft-tissue therapy for the management of musculoskeletal disorders and injuries of the upper and lower extremities: A systematic review by the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury management (OPTIMa) collaboration. Man Ther. 2016 Feb;21:18-34.

96. Trinh KH, et al. Expert Opinion: A Review of the Evaluation and Treatment of Heel Pain. Practical Neurology.com June 2015. Accessed 3/15/16.

97. Sutton, Deborah A. et al. The Effectiveness of Multimodal Care for Soft Tissue Injuries of the Lower Extremity: A Systematic Review by the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) Collaboration Journal of Manipulative & Physiological Therapeutics, Volume 39, Issue 2, 95 – 109.e2

98. M. S. Rathleff, C. M. Mølgaard, U. Fredberg, S. Kaalund, K. B. Andersen, T. T. Jensen, S. Aaskov, J. L. Olesen. High-load strength training improves outcome in patients with plantar fasciitis: A randomized controlled trial with

12-month follow-up Scand J Med Sci Sports 2015: 25: e292–e300