Dizziness and Vertigo

A Balanced Approach to the Dizzy Patient

Dizziness and vertigo account for over 8 million primary care visits in the U.S.each year. Dizziness is the leading presenting complaint for seniors over age 75. (1,2) Disequilibrium may arise from one or multiple anatomical structures. “Central” origins include the brain stem, cerebellum, or other supratentorial structures (or the vasculature supplying those tissues). “Peripheral” origins include: the vestibular, visual, and spinal proprioceptive systems. (3)

The cervical spine plays a critical role in the maintenance of balance. (4-7) In fact, Guyton states that the cervical spine is the most essential contributor toward equilibrium. (7) The term “cervicogenic vertigo,” first described in 1955 by Ryan and Cope, describes dizziness or disequilibrium originating from abnormal proprioceptive activity in the cervical spine. (9,10)

Although the exact mechanism of cervicogenic vertigo is debatable, most researchers ascribe to an altered “mechanoreceptive” theory. The upper cervical (C0-3) facet joints are highly innervated, supplying up to 50% of all cervical proprioceptive input. (11) The cervical spine muscles are extensively supplied with muscle spindles providing additional contributions. (12) Abnormal stimulation of the articular capsule and/ or muscular spindle mechanical receptors from joint dysfunction or muscle hyperactivity provides conflicting input with visual and vestibular afferents. This sensory mismatch between visual, vestibular, and cervical mechanoreceptive input “confuses” the brain into a temporary state of dizziness. (11,13-18) Other hypothetical models for cerviogenic vertigo include vascular compression and vasomotor changes secondary to irritation of the cervical sympathetic chain. (16,17)

Cervical spine proprioception may be affected by conditions that alter mechanoreceptive input including: degeneration, inflammation, joint dysfunction, disc lesion, muscle hypertonicity or trauma. (9,14,19-21) Dizziness frequently accompanies whiplash injury (22-24). Research suggests that between 25 and 80% of patients who suffer a whiplash injury will experience late onset dizziness, vertigo, or disequilibrium. (22,25,27,28) There is generally a temporal relationship between cervical spine injury and the onset of vertigo, although symptoms may be delayed from days to months. (21,29) Stress and anxiety are thought to be compounding factors for dizziness, as these conditions may increase muscle tone and sympathetic firing rates. (30,31)

Cervicogenic vertigo is suggested by a history of dizziness associated with cervical movement and concurrent neck pain. (32,33) Patients may complain of light-headedness, floating, unsteadiness, or general imbalance, but rarely true “spinning” vertigo (27). A sensation of “spinning” (i.e. true rotary vertigo) suggests a non-cervicogenic origin, possibly Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV). (21) Cervicogenic symptoms are generally episodic, provoked by movement and eased by maintaining a stable position. Continuous symptoms suggest a more central origin. Occipital headaches may accompany cervicogenic vertigo, but clinicians should be alert for the presence of a “severe” or “different” headache suggesting a cerebral origin.

Clinicians should search for clues that suggest a non-cervicogenic origin, including a history of head trauma, loss of consciousness, frequent unexplained falls, hearing loss, tinitis, ear “fullness,” earache, ptosis, facial or extremity paresthesia, visual disturbances, difficulty speaking, difficulty swallowing, ataxia, or a new medication, particularly anti-hypertensives or anti-depressants.

Cervicogenic dizziness is a diagnosis of exclusion, as there is no pathognomic test to confirm its presence. (34-35) Clinicians should be particularly astute and unhurried when evaluating vertigo. The common co-existence of vertigo and upper cervical discomfort has the potential to lull clinicians into a dangerous state of diagnostic complacency. Falsely assuming that someone with concurrent dizziness and neck pain is suffering from cervicogenic vertigo, without ruling out other potentially threatening causes of dizziness, could end in disaster.

The diagnosis of vertigo is complicated by the potential interaction of multiple systems with similar presentations. (36) The most common cause of vertigo is BPPV, which is responsible for between 17 and 42% of all cases. (3,37) One of the more sobering causes of vertigo, particularly for manual therapists, is vertebrobasilar arterial insufficiency (VBAI). Astute clinicians will be more likely to recognize the symptom constellation of VBAI, as vertigo is rarely an isolated symptom of this disorder. (36,39)

Assessing vital signs may provide insight. Blood pressure measurement may help identify patients with hypertension or orthostatic hypotension. Clinicians should confirm that patients are afebrile to rule out infection. Otoscopic evaluation may identify middle ear problems. Aucultation should be performed for the heart, lungs, and carotid arteries. Clinicians should palpate the head and neck for signs of lymph node swelling. Clinicians must perform a thorough neurologic exam, including assessment of cranial nerve function and observing for signs of upper motor neuron lesion, including hyperreflexia or pathologic reflexes. Cerebellar function can be assessed with Romberg, finger to nose, heel to knee, and gait assessment.

The assessment of vertigo includes the performance of various provocative rotary maneuvers, intended to reproduce complaints. When testing, clinicians should be concurrently assessing for the presence of nystagmus. “Vertical” nystagmus (imagine the pupil is a basketball being dribbled up and down) suggests a central origin. “Horizontal” nystagmus (imagine a basketball being dribbled toward the side of the patient’s eye) suggests a peripheral origin. Horizontal nystagmus of cervicogenic or vestibular origin generally occurs abruptly after head movements and progressively diminishes as the brain adapts. Nystagmus from VBAI presents as a late onset (after many seconds) and progressively intensifies. (11)

One complicating factor in the differentiation of cervicogenic vertigo versus BPPV is that most provocative movements concurrently stimulate both cervical spine proprioceptors and the vestibular apparatus. The Head-fixed/body-turn test (aka Neck torsion test) aims to isolate cervical mechanoreceptors without stimulating the vestibular apparatus. (21,41) The neck torsion test is performed with the patient rotating his or her body on an exam stool while the clinician stabilizes the head, thereby minimizing vestibular input. Reproduction of dizziness or nystagmus when the head is stable suggests a cervical component. (42-44) Nystagmus during the neck torsion test is of questionable significance, as it may be a normal cervical-occular reflex in up to 50% of the population. (21,41) Patients with cervicogenic vertigo may demonstrate slower eye tracking movements when their head is turned. (21,45,77) Another screening tool to differentiate BPPV and cervicogenic vertigo is simple head rotation. Level rotation should exacerbate cervicogenic vertigo symptoms, while those with BPPV are less likely to report increased symptomatology.

The Dix-Hallpike test is a classic assessment for BPPV but may also provoke cervicogenic vertigo. The test is performed by rotating the patient’s head 45 degrees and quickly bringing the long-sitting patient into a supine position with their head extended off of the table to 30 degrees. The position is held for at least 15 seconds and the patient is asked to report any vertigo while the clinician observes for nystagmus. The patient is returned to the upright position and the test is repeated on the opposite side. Reproduction of vertigo or nystagmus is a positive test.

Findings more consistent with a diagnosis of cervicogenic vertigo include loss of cervical range of motion, upper cervical tenderness, and upper cervical segmental joint restriction. Deep palpation of the suboccipital region may reproduce vertigo in some patients. (40) Clinicians often note hypertonicity in the suboccipital, paracervical, trapezius, SCM, and pectoral muscles. A cyclic pattern of dysfunction has been identified between altered cervical proprioception and hypertonicity in the SCM and upper trapezius that may fuel cervicogenic vertigo. (21,38,42) After more threatening causes have been excluded, a trial of spinal manipulation may serve as the best diagnostic test for cervicogenic vertigo.

Clinicians should assess for signs of functional deficit, including upper crossed syndrome or weakness in the deep neck flexors. Deep neck flexor weakness has been identified as a primary component of cervicogenic headache and may very well be a contributor to cervicogenic vertigo. Deep neck flexor strength may be assessed with the deep neck flexor endurance test.

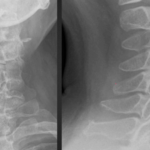

Plain film evaluation of cervicogenic vertigo is usually non-contributory. (36) MRA or arterial Doppler is appropriate in cases where VBAI is suspected. CT or MRI with contrast can help rule out suspicions of CNS pathology.

In addition to BPPV and VBAI, the differential diagnosis for cervicogenic vertigo includes other labrynthine or vestibular disorders, concussion, intracranial bleed, perilymphatic fistula, CNS ischemia/stroke, neoplasm, infections, intracranial swelling, migraine, carotid sinus syndrome, intoxication, or drug toxicity. (19) Again, clinicians must recognize that patients may present with multiple diagnoses.

Cervicogenic vertigo is amenable to conservative treatment, including manual therapy. (16,21,29, 47-49,54,57) Since cervicogenic vertigo, by definition, results from upper cervical dysfunction, spinal manipulation is a cornerstone of treatment. Several studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of spinal manipulation for cervicogenic vertigo. (11,59,60) One of the world’s foremost musculoskeletal experts, Karel Lewit, M.D., states, “In no field is manipulation more effective than in the treatment of disturbances of equilibrium.” (61) Fitz-Ritson demonstrated a 90.2 success rate when utilizing manipulation for the treatment of post-traumatic cervicogenic vertigo. (17) Clinicians should assess for and treat associated restrictions in the lower cervical and thoracic regions. In patients whom HVLA manipulation is contraindicated, clinicians may consider utilizing low-force manipulation, mobilization, or sustained natural apophyseal glides (SNAG) as described by Reid. (62,78)

Because cervicogenic vertigo is multi-factoral in origin, successful management requires a multi-faceted approach. Therapy must address associated soft tissue components. Myofascial release and/or stretching may be needed in the suboccipital, SCM, upper trapezius, levator, and pectoral muscles. Postural correction may be necessary for upper crossed syndrome, and breathing exercises are appropriate for those with dysfunctional respiration. Clinicians should be particularly cognizant to assess and correct for weakness in the deep neck flexor muscles, (i.e. longus colli and longus capitis). Physical therapy modalities, including ice, heat, ultrasound, e-stim, or traction may be appropriate for associated maladies.

Cervicogenic vertigo patients with co-existent BPPV will require the addition of vestibular rehabilitation therapy. (63,64) Several studies have demonstrated improved outcomes by incorporating vestibular rehabilitation with traditional manual therapy. (16, 21,57,68) Vestibular rehabilitation should include canalith repositioning maneuvers, performed in office, and prescription of home-based Brandt-Daroff or vestibular habituation training exercises. In patients with BPPV, a single canalith repositioning maneuver produces resolution of symptoms in over 70% of patients. (69-73) The addition of vibration does not enhance the effectiveness of this maneuver. (74,75) Brandt-Daroff exercises resolve symptoms in 98% of BPPV cases within two weeks. (76)

The pharmacologic addition of labrynth sedation may be necessary for acute cases, and patients not responding to a brief trial of conservative therapy will require additional diagnostic workup and/or medical referral to a neurologist or ENT specialist.

References

- Lalwani AK. Vertigo dysequilibrium and imbalance with aging. In: Jackler RK, Brackmann DE, editors. Neurotology. St. Louis: Mosby; 1994. p. 527-34.

- Colledge NR, Barr-Hamilton RM, Lewis SJ, Sellar RJ, Wilson JA. Evaluation of investigations to diagnose the cause of dizziness in elderly people: a community based controlled study. British Medical Journal 1996;313:788–93

- Albernaz PLM, Cruz NA, Ganaça MM. As doenças vestibulares periféricas e centrais: classificação, diagnóstico e tratamento. Rev Bras Otorinolaring 1968:541-8.

- de Jong PTVM, et al. Ataxia and nystagmus induced by injection of local anesthetics in the neck. Ann Neurol 1977; 1:240-246.

- Abrahams VC, Falchetto S. Hind leg ataxia of cervical origin and cervico-lumbar spinal interactions with a supratentorial pathway. J Physiol 1969; 203:435-447.

- Fitz-Ritson D. Neuroanatomy and neurophysiology of the upper cervical spine. In: Vernon H. ed. The Upper Cervical Syndrome: Chiropractic Diagnosis and Treatment. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkens, 1988:48-85.

- Guyton AC. Textbook of Medical Physiology. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger, 1989.

- RyanMS,CopeS.Cervicalvertigo.Lancet.1955;2:1355- 1358.

- FurmanJM,CassSP. BalanceDisorders: A Case-StudyAp- proach. Philadelphia, Pa: FA Davis; 1996.

- Hulse M. Disequilibrium caused by a functional disturbance of the upper cervical spine, clinical aspects and differential diagnosis. Manual Medicine 1983; 1(1):18-23.

- Cooper S, Daniel PM (1963) Muscle spindles in man: their morphology in the lumbricals and the deep muscles of the neck. Brain 86:563–586.

- Telian AS, Shepard NT. Update on vestibular rehabilitation therapy. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1996;29:359-71.

- Wyke B. Neurology of the cervical joints. Physiotherapy 1979; 65(3):72-76.

- Baloh RW. Dizziness, hearing loss and tinnitus: the essentials of neurotology. Philidelphia: FA Davis Company, 1984: 152.

- Biesinger E. Vertigo caused by disorders of the cervical vertebral column. Adv Otorhinolaryngol 1988;39:44-51.

- Fitz-Ritson D. Assessment of cervicogenic vertigo. JMPT 1991;14:193-198.

- Jinliang Zuo, Jianlong Han, Siqiang Qiu, Fanghai Luan, Xinwei Zhu, Haoyuan Gao, Anmin Chen, Neural reflex pathway between cervical spinal and sympathetic ganglia in rabbit: implication for pathogenesis of cervical vertigo. The Spine Journal (2013)

- Brandt T, Bronstein AM. Cervical vertigo J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001;71:8-12

- Eduardo S. B. Bracher, DC, MD,a Clemente I. R. Almeida, MD,b Roberta R. Almeida, MD,b,c André C. Duprat, MD,b and Cheri B. B. Bracher, DCa A Combined Approach for the Treatment of Cervical Vertigo J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2000;23:96-100)

- Wrisley DM, Sparto PJ, Whitney SL, Furman JM. Cervicogenic dizziness: A review of diagnosis and treatment. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2000;30:755-766.

- Oostendorp RAB, Van Eupen AAJM, Van Erp J, Elvers H. Dizziness following whiplash injury: a neuro-otological study in manual therapy practice and therapeutic implication. The Journal of Manual and Manipulative Therapy 1999;7(3):123–30.

- Rubin W. Whiplash with vestibular involvement. Arch Otolaryngol. 1973;97:85-87.

- Spitzer WO, Skovron ML, Salmi LR. Scientific monograph of the Quebec task force on whiplash-associated disorders: redefining whiplash and its management. Spine 1995;20(Suppl 8):1-73.

- Endo K, Ichimaru K, Komagata M, Yamamoto K. Cervical vertigo and dizziness after whiplash injury. Eur Spine J. 2006 Jun;15(6):886-90. Epub 2006 Jan 24.

- Takasaki, H., V. Johnston, et al. (2011). “Driving with a chronic whiplash-associated disorder: a review of patients’ perspectives.” Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation 92(1): 106-110.

- Spitzer WO, Skovron ML, Salmi LR. Scientific monograph of the Quebec task force on whiplash-associated disorders: redefining whiplash and its management. Spine 1995;20(Suppl 8):1-73.

- BrownJJ. Cervical contributions to balance: cervical vertigo. In: Berthoz A, Vidal PP, Graf W, eds. The Head Neck Sensory Motor System. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1992:644-647.

- Basmajian JV. Basis for autonomic regulation. In: Basmajian J, editor. Biofeedback principle and practice for clinicians. Baltimore:William & Wilkins; 1989. p. 37-48.

- Hatch JP. Headache. In: Gatcher RJ, Blanchard EB, editors. Psychophysiologycal disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychologycal Association; 1994. p. 111-49.

- Ojala M, Palo J. The aetiology of dizziness and how to examine a dizzy patient. Ann Med 1991;23:225-30.

- Stenger HH. Análisis del vertigo; exploración del nystagmo espontáneo y del provocado. In: Berendes J, Link R, Zöllner F, editors. Tratado de otorrinolaringologia. Barcelona: Editorial Cientifico Médica; 1969. p. 603-46.

- Huijbregts P, Vidal P. Dizziness in orthopaedic physical therapy practice: Classification and pathophysiology. J Manual Manipulative Ther 2004;12:199-214.

- Furman JM, Cass SP. Balance Disorders: A Case-Study Approach. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis, 1996.

- Cote P, Mior SA, Fitz-Ritson D. Cervicogenic vertigo: a report of three cases. 0008-3194/91/89-94/JCCA 1991

- Bhattacharyya N, Baugh RF, Orvidas L, Barrs D, Bronston LJ, Cass S, Chalian AA, Desmond AL, Earll JM, Fife TD, Fuller DC, Judge JO, Mann NR, Rosenfeld RM, Schuring LT, Steiner RWP, Whitney SL, Haidari J. Clinical practice guideline: benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2008;139:S47-81.

- Weiner HL, Levitt LP. Neurology for the House Officer. 4th ed. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkens, 1989.

- Norre M, Stevens A. Le nystagmus cervical et les troubles fonctionnels de lacolonne cervicale. Acta Oto-Rhino-Larynologica Belgica 1976; (30)5.

- Phillipszoon AJ. Neck torsion nystagmus. Pract Oto-Rhi- no-Laryngologist. 1963;25:339-344.

- Huijbregts P, Vidal P. Dizziness in orthopaedic physical therapy practice: Classification and pathophysiology. J Manual Manipulative Ther 2004;12:199-214.

- Norre ME, Stevens A. Cervical vertigo. Acta Oto-Rhino-Larynologica Belgica 1987; 41(3):436-52

- Fitz-Ritson D. Assessment of cervicogenic vertigo. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1991 Mar-Apr;14(3):193-8.

- Tjell C, Rosenhall U. Smooth pursuit neck torsion test: a specific test for cervical vertigo. Am / Otol, 1998;19:76- 81.

- Galm R, Rittmeister M, Schmitt E. Vertigo in patients with cervical spine dysfunction. Eur Spine J 1998;7:55–58.

- Karlberg M, Magnusson M, Malmstrom EM, Melander A, Moritz U. Postural and symptomatic improvement after physiotherapy in patients with dizziness of suspected cervical origin. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1996;77:874–882.

- Wing LW, Hargrave-Wilson W. Cervical vertigo. Aust N Z J Surg 1974;44:275–277.

- Calm R, Rittmeister M, Schmitt E. Vertigo in patients with cervical spine dysfunction. Eur Spine 1. 1998;7:55-58.

- Reid SA, Rivett DA. Manual therapy treatment of cervicogenic dizziness: a systematic review Manual Therapy 10 (2005) 4–13

- Oostendorp RAB, Van Eupen AAJM, Van Erp JMM, Elvers HWH. Dizziness following whiplash injury: a neurological study in manual therapy practice and therapeutic implication. / Manual Manip Ther. 1999;7:123-130.

- Brunarski D. Autonomic nervous system disturbances of cervical origin including disorders of equilibrium. In: Vernon H, ed.Upper Cervical Syndrome. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins,1988:

- Fitz-Ritson D. The chiropractic management and rehabilitation of cervical trauma. JMPT 1990;13(1):17-25.

- Lewit K. Disturbed balance due to lesions of the cranio-cervical junction. J Orthop Med 1998; 3:58-61.

- Reid SA, Rivett DA, Katekar MG, Callister R. Sustained natural apophyseal glides (SNAGs) are an effective treatment for cervicogenic dizziness. Man Ther. 2008 Aug;13(4):357-66. Epub 2007 Oct 22.

- Bourgeois PM, Dehaene I. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Acta Neurol Belg 1988; 88:65-74.

- Norre ME, Beckers AM. Vestibular habituation training. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1988; 114:883-886.

- Karlberg M, et al. Postural and symptomatic improvement after physiotherapy in patients with dizziness of suspected cervical origin. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1996; 77:874-882.

- Dal T, Ozluoglu LN, Ergin NT. The canalith repositioning maneuver in patients with benign positional vertigo. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2000;257:133-136.

- Herdman SJ, Tusa RJ, Zee DS, Proctor LR, Mattox DE. Single treatment approaches to benign paroxysmal posi- tional vertigo. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993; 119:450-454.

- Wolf IS, Boyev KP, Manokey BJ, Mattox DE. Success of the modified Epley maneuver in treating benign parox- ysmal positional vertigo. Laryngoscope. 1999; 109:900- 903.

- Wolf M, Hertanu T, Novikov I, KronenbergJ. Epley’s ma- noeuvre for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a pro- spective study. Clin Otolaryngol. 1999;24:43-46.

- Macias JD, Ellensohn A, Massingale S, Gerkin R. Vibration with the canalith repositioning maneuver: a prospective randomized study to determine efficacy. Laryngoscope. 2004 Jun;114(6):1011-4.

- Hain TzzC, Helminski JO, Reis IL, Uddin MK Vibration Does Not Improve Results of the Canalith Repositioning Procedure. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000; 126(5):617-622.

- Brandt T, Daroff RB. Physical therapy for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Arch Otolaryngol. 1980;106: 484-485.

- Bronstein AM, Hood JD (1986) The cervico-ocular reflex in normal subjects and patients with absent vestibular function. Brain Res 373:399–408.

- Reid SA, Callister R, Snodgrass SJ, Katekar MG, Rivett DA. Manual therapy for cervicogenic dizziness: Long-term outcomes of a randomised trial. Manual Therapy 20, 2015, 148-56