An Uncommon Cause of Hip Pain in an Adult: Healed Legg-Calve-Perthes Disease

Hip pain and decreased range of motion are common complaints in the chiropractic office; however, the underlying cause of these complaints is wide ranging and can present as a diagnostic challenge. Our patient was a 29-year-old male with chronic left hip pain since his early childhood; however, he had not sought treatment for this complaint until his initial visit to his chiropractic physician. Radiographs of the lumbar spine were performed in which the cause of his chronic hip was revealed.

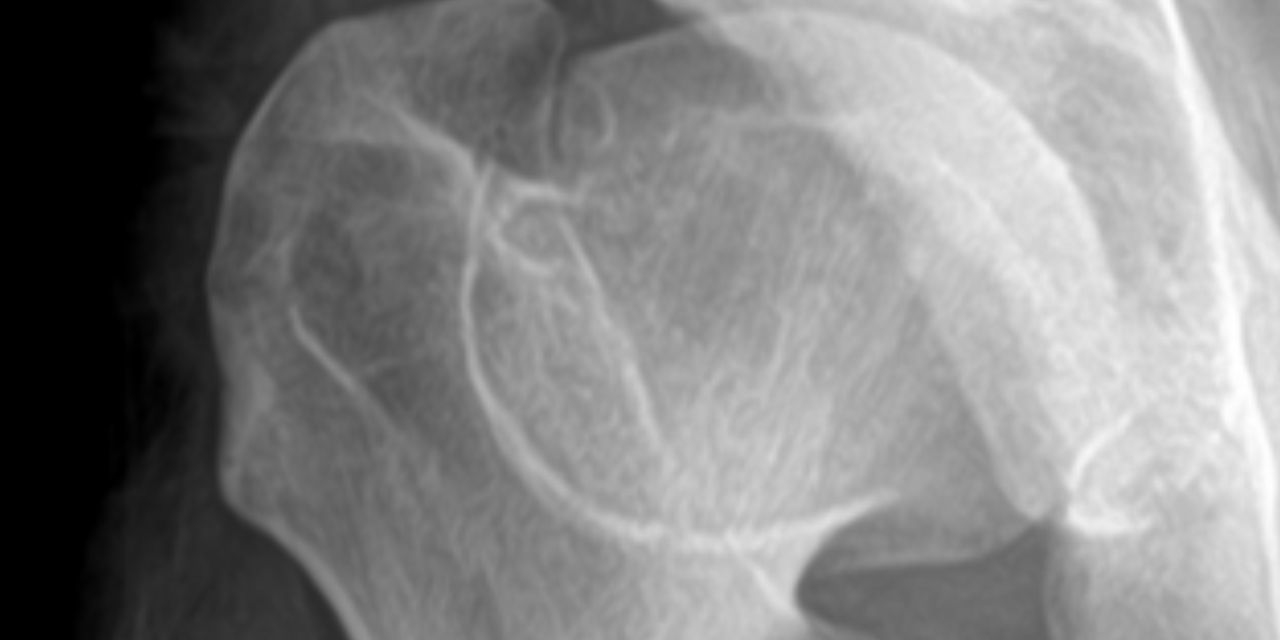

Radiographs of the left hip reveal widening and flattening of the femoral head (coxa plana), widening of the proximal femoral neck (coxa magna), and a thin curvilinear sclerotic line extending across of the femoral neck (“sagging rope sign”). These findings illustrate the classic appearance of the advanced healed stage (stage 4) of Legg-Calve-Perthes disease (LCPD). Note that the acetabulum is usually of normal contour without femoral head dislocation/ subluxation; this is an important differentiating factor when comparing LCPD to congenital dysplasia of the hip, in which acetabular flattening and femoral subluxation/ dislocation are typical findings.

To understand the resultant radiographic appearance of the hip in the remodeled stage of LCPD, it is important to review the pathogenesis and resulting radiographic finding that occur during the active phases of LCPD. Legg-Calve-Perthes disease results from interruption of the blood supply to the capital femoral epiphysis in childhood, resulting in osteonecrosis and chondronecrosis, which may result in progressive deformity of the femoral head and secondary degenerative osteoarthritis1. This condition is found in approximately 1 in 10,000 children; however, this range varies greatly throughout the literature. The typical age range is 3-12 years of age (peak at 5-6 years of age) with a 5:1 male to female ratio2. LCPD is bilateral in 10-20% of cases, but an important consideration is that the changes are asymmetric and asynchronous, with each hip demonstrating a different stage of the disease. LCPD can be idiopathic or due to other etiology that would disrupt blood flow to the femoral epiphysis, such as trauma (macro or repetitive microtrauma), coagulopathy, or steroid use. It is important to note that up to 75% of affected patients have some form of coagulopathy3. Other risk factors include familial predisposition, low socioeconomic status, low birth weight, short stature, and exposure to second hand smoke4.

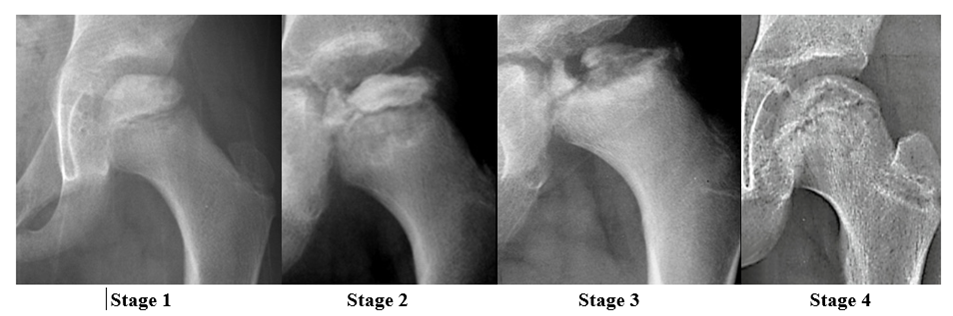

There are several classifications systems used to classify the stages of LCPD; however, this paper will use the Waldentrom classification, which refers to the associated radiographic findings for each stage. The initial stage (stage 1) results from infarction, which produces a smaller and sclerotic epiphysis with medial joint space widening. This stage may be radiographically occult for 3-6 months. The fragmentation stage (stage 2) typically begins with a subchondral lucent line (crescent sign) and then progresses to fragmentation and resorption of bone, resulting in femoral head collapse and patchy sclerotic density. The re-ossification stage (stage 3) occurs as the ossific nucleus undergoes re-ossification in which the necrotic bone is resorbed and new bone replaces. The healing or remodeling stage (stage 4) consists of femoral head remodeling until skeletal maturity. Once fully healed, the remodeled hip has the classic coxa plana, coxa magna, and “sagging rope sign” radiographic features. Dependent upon proper treatment and other patient variables, the degree of resultant deformity will vary amongst patients.

Early detection of this condition is important, as activity restriction and protected weight bearing until re-ossification of the femoral head is complete can be beneficial. Those that respond to conservative therapy will typically show healing in 2-4 years. Literature has not shown braces, casts, or orthotics to be beneficial4. Femoral or pelvic osteotomy may be required in some cases in older children (surgery is not typically beneficial in children <8 years old). Early diagnosis of LCPD in childhood is important in order to initiate potentially joint-preserving therapies5; however, recognition later in life is also beneficial to the patient to address the resulting femoral-acetabular impingement and likely premature osteoarthritis. Hip arthroscopy has been shown to be an effective treatment to address the osseous and cartilaginous abnormalities that are found in the healed LCPD affected hip6.

Editor’s Note: Dr. Ruof is presenting the course Cervical Spine Trauma Including Case Studies on October 3, 2023, and the course Pathologic, Insufficiency, and Stress Fractures – How can I diagnose and differentiate? on January 30, 2024. Register for both courses today!

References:

- Ibrahim T, Little D. The pathogenesis and treatment of Legg-Calve-Perthes disease. J Bone Joint Surg Rev. 2016 Jul 19;4(7):e4.

- Barker DJ, Hall AJ. The epidemiology of Perthes’ disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986: 209:89-94.

- Vosmaer A, Pereira RR, Koenderman JS, Rosendaal FR, Cannegieter SC. Coagulation abnormalities in Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010 Jan;92(1):121-8.

- Mills S, Burroughs KE. Legg-Calve-Perthes Disease. [Updated 2022 Jul 11]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan.

- Mont MA, Jones LC, Hunderford DC. Nontraumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head: ten years later. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006; 88:1117-1132.

- Freeman CR, Jone K, Thomas Byrd JW. Hip arthroscopy for Legg-Calve-Perthes disease: minimum 2-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2013 Apr;29(4):666-74.