The Elbow Flexion Test and Cubital Tunnel Syndrome

Ulnar nerve entrapment at the elbow is often referred to as “Cubital Tunnel Syndrome.” Cubital tunnel syndrome is second only to carpal tunnel syndrome as a leading compressive neuropathy (1).

The cubital tunnel is defined by the retrocondylar groove on the posterior aspect of the medial epicondyle and superiorly by a fascial retinaculum. Elbow flexion requires the ulnar nerve to both stretch and slide through the cubital tunnel. As the elbow flexes, the distance between the medial epicondyle and olecranon increases. Flexion concurrently causes stretch of the retinaculum resulting in ovoid deformation of the cubital tunnel, diminishing the tunnels volume. The ulnar nerve is fairly flexible and can temporarily stretch up to 5mm, but sustained traction or compression may exceed the nerves resiliency, leading to symptoms of cubital tunnel syndrome (2).

Causes of Irritaion

In addition to sustained traction, ulnar nerve irritation may be caused by; Compression from direct or repetitive trauma (like leaning on the elbow on a desk or soft tissue hypertrophy or osteophytes) or recurrent subluxation resulting in friction and inflammation.

The two most common sites of ulnar nerve entrapment at the elbow are 1) within the true cubital tunnel and 2) slightly distal to the tunnel between the two heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris. Entrapment distally between the heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris, or at a less common site, proximally at the medial intramuscular septum, limits nerve glide and causes the nerve to be tractioned over the joint during flexion.

Who is at Risk?

Cubital tunnel is commonly seen in baseball, tennis and racquetball players. Also, workers who maintain sustained elbow flexion, such as holding a tool or telephone, or those who press the ulnar nerve against a hard surface, like a desk, are at increased risk. Elbow valgus or varus increases risk as does diabetes and obesity (3). Women have significantly increased fat at the medial aspect of the elbow providing greater protection, therefore, it is not surprising that cubital tunnel syndrome affects men 3-8 times as often as women (4).

Patients presenting with cubital tunnel often complain of paresthesia or pain extending distally from the medial epicondyle to the 4th and 5th digit. Symptoms may vary from vague hypersensitivity to pain. Since motor fibers are located deep to sensory fibers, sensory irritation precedes motor deficits. The condition is often progressive. Nocturnal symptoms are common. Symptoms may infrequently radiate proximally toward the shoulder or neck (5). In more advanced cases, discomfort may be accompanied by loss of grip strength and fine motor control. Late stages may include intrinsic muscle wasting.

Diagnosis

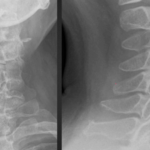

The diagnosis of cubital tunnel is based primarily on history and clinical findings. Use of the Disabilities of Arm, Shoulder and Hand index (DASH) will assist with outcome assessment and documentation of the complaint. Palpation may reveal tenderness at the posterior aspect of the medial epicondyle, and palpation of the ulnar nerve during elbow flexion will screen for recurrent subluxation of the nerve. Tinel sign may be positive in symptomatic patients and in up to 1/4th of asymptomatic patients. The “Elbow flexion test” is the best diagnostic maneuver for identifying cubital tunnel (6,7,8). The test entails maintaining shoulder abduction while flexing the elbow past 90 degrees, supinating the forearm, extending the wrist with thumb/ index opposition (see figure 1). A positive test results in the reproduction of the chief complaint within 60 seconds. Weakness is assessed by strength testing in finger abduction, adduction and pinch grip. Motor assessment may include a grip dynamometer and pitch meter. Clinicians should examine the 4th and 5th digit for clawing (Froment’s sign) or abduction (Wartenberg’s sign).

Radiographs of the elbow are of limited value except in cases of trauma or suspected bony encroachment. Radiographic evidence of osteophytes, loose bodies or calcification of the medial collateral ligament is significant. An EMG is generally not necessary unless the diagnosis is in question or the condition fails to respond to conservative care. MRI is of limited value except to define ganglions, neuromas, and aneurysms of the ulnar artery. Differential diagnosis considerations include carpal tunnel syndrome, cervical disc herniation, medial epicondylitis, thoracic outlet syndrome, space-occupying lesion, Pancoast tumor, syringomyelia or alternate site of ulnar nerve entrapment (i.e. hand or shoulder).

Treatment

Management of ulnar nerve compression includes rest, ice, pulsed ultrasound, nerve mobilization techniques, myofascial release techniques, adjusting associated osseous subluxations and patient education. Activity modification to limit prolonged flexion and direct pressure is the key to successful management. A night-time elbow splint that limits flexion may be helpful (45 degrees of flexion is thought to be the optimal position to decrease intraneural pressure) (9). Also, a protective pad to limit repetitive daytime trauma from work or sports may prove useful. Manual therapy techniques should avoid direct pressure to the irritated nerve. Nerve mobilization may be accomplished by instructing the patient to transition from an “outstretched handshake” position to the “elbow flexion test” position and back while maintaining a pain-free range of motion. Rehab is focused on increasing strength of the flexors & extensors both isometrically and isotonically within a pain-free 0-45 degree range. Stretching the pronators is useful.

Consideration of surgical decompression is warranted for symptoms lasting over 12 weeks or in cases of significant motor deficit. Surgical management includes in-situ decompression, medial epicondylectomy, and anterior transposition.

Conclusion

A timely and accurate diagnosis combined with a well-conceived treatment plan can often save patients from more aggressive options. Cubital tunnel syndrome is another example of a common condition that allows chiropractors to showcase their excellence in conservative musculoskeletal care.

Figure 1:

- Nicholas, J.A. The Upper Extremity in Sports Medicine, CV Mosby, 1990 p.343

- Wilgis EF, Murphy R. The significance of longitudinal excursion in peripheral nerves. Hand Clin. Nov 1986;2(4):761-6.

- Charness ME. Unique upper extremity disorders of musicians. In: Millender, ed. Occupational Disorders of the Upper Extremity. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone; 1992: 227-52.

- Contreras MG, Warner MA, Charboneau WJ. Anatomy of the ulnar nerve at the elbow: potential relationship of acute ulnar neuropathy to gender differences. Clin Anat. 1998;11(6):372-8.

- Sarwark, J.F., Essentials of Musculoskeletal Care, American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons 4th ed, 2010, p.275

- Buehler MJ, Thayer DT. The elbow flexion test. A clinical test for the cubital tunnel syndrome. Clin Orthop. Aug 1988;(233):213-6.

- Rayan GM, Jensen C, Duke J. Elbow flexion test in the normal population. J Hand Surg [Am]. Jan 1992;17(1):86-9.

- Ochi K, Horiuchi Y, Tanabe A, Morita K, Takeda K, Ninomiya K. Comparison of shoulder internal rotation test with the elbow flexion test in the diagnosis of cubital tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. May 2011;36(5):782-7.

- Yamaguchi K, Sweet FA, Bindra R. The extraneural and intraneural arterial anatomy of the ulnar nerve at the elbow. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. Jan-Feb 1999;8(1):17-21. Figure 1: