Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome

Introduction & Etiology

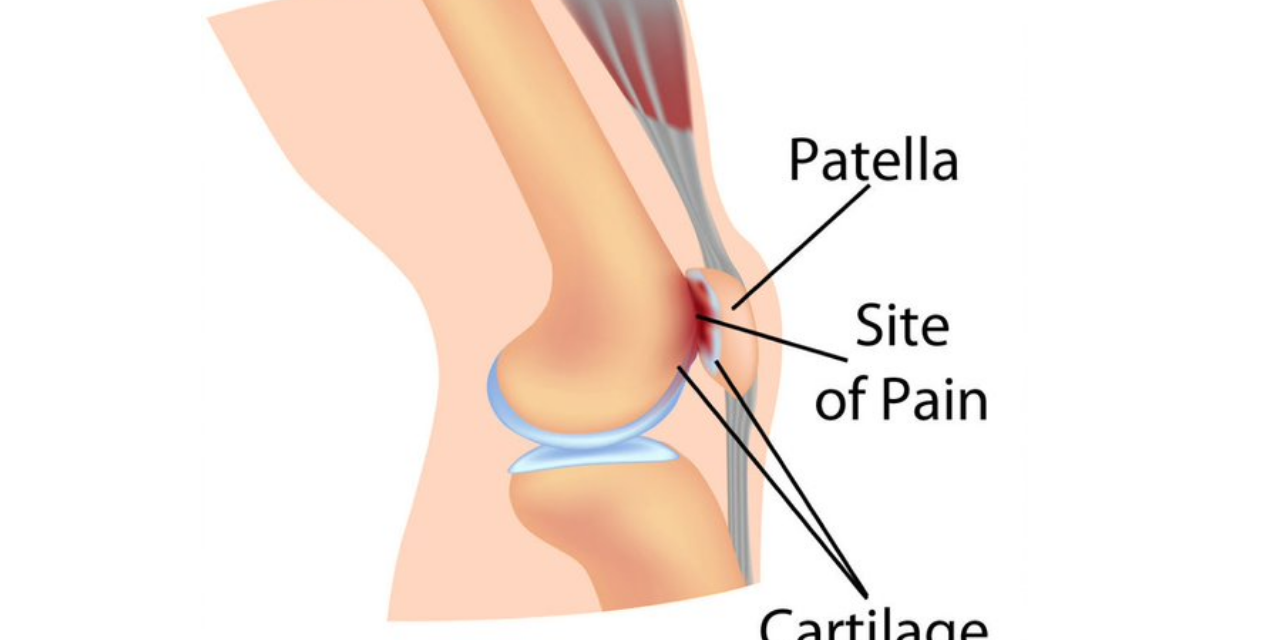

The patellofemoral joint is a common site of pain. (1) The broad term “Patellofemoral pain syndrome” (PFPS) encompasses a spectrum of signs and symptoms. The spectrum begins with asymptomatic functional malalignment of the patella and ends in severe patellofemoral arthritis. The diagnosis of “Chondromalacia patellae” (CMP) occupies the mid-portion of the PFPS continuum, beginning with visible cartilage alterations and eventually leading to patellofemoral arthritis. (2) Chondromalacia may begin at any age and is commonly found in teenagers. (3) The incidence of CMP increases with age and is more common in females. (3)

Retropatellar cartilage breakdown is the hallmark feature of chondromalacia. (4) Chondromalacia progresses in the following step-wise fashion: cartilaginous swelling and softening (stage 1), partial thickness fissuring (stage 2), full thickness fasciculations (stage 3), and cartilage destruction with exposure of subchondral bone (stage 4). (5) Stage 4 chondromalacia represents the onset of DJD and is indistinguishable from that disorder. (5)

Patellar cartilage differs from typical joint cartilage in many ways. Patellar cartilage is incongruently thicker in certain areas, more permeable, less stiff, and more compressible. (6) The remaining etiologic factors for CMP are nearly identical to those of patellofemoral pain syndrome. Imbalanced actions of the static and dynamic knee stabilizers can alter the distribution of forces to the patellofemoral articular surface and related soft tissues. These biomechanical tracking stressors are compounded through activities of daily living, causing irritation and eventually wear to the patellofemoral cartilage.

Any factor that alters normal patellofemoral mechanics is a risk factor for chondromalacia patellae. This includes lateral tracking disorders, tightness in the lateral knee capsule, weakness of the vastus medialis or quadriceps, pes planus, hip abductor weakness, joint overloads/overuse, trauma, patellar hypermobility, and muscle imbalance, particularly quadriceps or iliotibial band hypertonicity and vasus medialis or quadriceps weakness. (7-10) Weakness in the quadriceps or hamstring muscles increases one’s risk of developing patellofemoral pain three to five-fold. (11) Weakness in the hip abductors is common in patients with knee pain and is a significant contributor to patellofemoral pain. (12,13) Some researchers question whether hip abductor weakness is a cause or effect of patellofemoral pain. (40) Additional risk factors for the development of CMP include obesity, hypermobility/instability, prior cruciate ligament injury, and prior trauma, fracture, or patellar subluxation. (3,14-16)

Clinical Presentation

Clinically, CMP patients present with complaints nearly indistinguishable from PFPS. Symptoms include dull peripatellar pain that is exacerbated by activities that load the joint, including prolonged walking, running, squatting, kneeling, jumping, arising from a seated position, or stair climbing – especially walking down stairs or downhill. (2,18). Disruption of patellofemoral cartilage may result in crepitus, intermittent locking, or giving way. (18)

Clinical evaluation of CMP should be directed toward identifying factors that create imbalanced force on the patella, i.e., PFPS. Patients suffering with patellofemoral pain often have hypertonic soleus, hamstring, iliopsoas, piriformis, and thigh adductor muscles with tightness in the iliotibial band and posterior hip capsule. (7,19,20) Weakness in the quadriceps or hamstring muscles increases one’s risk of developing the problem three to five-fold. (11) Weakness in the gluteus maximus or medius is common in patients with knee pain and contributes to PFPS. (12,13) Gluteus medius weakness may be assessed by observing for pelvic drop or knee valgus (Trendelenburg sign) when performing a single leg stand, overhead squat test, single leg squat, or single leg 6″ step down. Patients with anterior knee pain frequently have a greater prevalence of trigger points in their hip, thigh, and lumbar spine muscles. (41,42)

Palpation generally reveals peripatellar tenderness with exacerbation of symptoms upon patellar compression. Clinicians may consider alternatives to the Patellar grind test, (a/k/a “Clarke sign”), as this assessment has been shown to be unreliable, and may even generate new complaints. (21,22) Patellar mobility may be assessed with the Patellar Glide test and Patellar tilt test or by observing patellar tracking during active knee flexion/ extension (Patellar tracking assessment). (23) Static assessment of patellofemoral orientation is an unreliable measurement tool. (24,25) Historically, increased Q angles were thought to increase lateral pressures and were considered an etiologic factor. (26) Newer studies show that normal Q angles vary from 10 to 20 degrees and are similar in symptomatic and non-symptomatic patellofemoral patients. (27,28)

Differentiation of meniscal pain from patellofemoral pain may be accomplished by having the patient perform a two-legged squat. Meniscal pain is generated at the bottom of the squat, while patellofemoral pain is present during descent and ascent.

Diagnostics & Differential

Knee radiographs may be necessary to rule out fracture in those with a history of trauma or osteoarthritis and in patients older than 50. Radiographs may also be appropriate in patients with significant swelling, a recent history of knee surgery and in those whose pain does not improve with a trial of treatment. (29) Radiographic assessment of CMP would include a lateral, AP, tunnel, and patellofemoral (merchant or sunrise) view.

Chondral lesions are often difficult to diagnose by plain x-ray. The presence of osteophytes, cysts, subchondral sclerosis, and articular space narrowing is indicative of cartilaginous injury. (30) MRI is the modality best suited to identify cartilage lesions. (31) Clinicians should recognize that cartilage lesions are exceptionally prevalent in symptomatic populations. (43) Like so many other degenerative conditions, there appears to be little correlation between the radiographic severity of CMP and the patient’s subjective complaints. (32)

The differential diagnosis for anterior knee pain includes: fracture, infection, neoplasm, patellar or quadriceps tendinopathy, bursitis and cartilaginous irritation including osteochondritis dissecans, and patellofemoral arthritis. Additional considerations would include Sinding-Larsen-Johansson syndrome, plica, iliotibial band syndrome, symptomatic bipartite patella and referred pain from the spine or hip. (33)

Management

If left untreated, CMP may result in premature degenerative joint disease. (31) Management of CMP should progress from minimization of aggravating factors and anti-inflammatory measures to long-term correction of functional deficits. Decreasing fear-avoidance behavior may lead to improved outcomes. (10) Lifestyle modification may be necessary to reduce pain-provoking activities, especially running, jumping and activities that induce a valgus stress. Athletes should avoid allowing their knee to cross in front of their toes while squatting. Electrotherapy and ice may be useful initially for reduction of pain and inflammation. NSAIDS or anti-inflammatory medication may provide short-term benefit for relief of pain and inflammation.

Myofascial release and stretching should be directed at hypertonic muscles, including the TFL, gastrocnemius, soleus, hamstring, piriformis, hip rotators and psoas. Myofascial release or IASTM may be appropriate for tightness in the iliotibial band, posterior hip capsule and lateral knee retinaculum.

Since gluteus medius and VMO weakness are key factors in the development of PFPS and knee pain, strengthening exercises are generally necessary for those muscles. (34) Stabilization exercises may include: pillow push (push the back of your knee into a pillow for 5-6 seconds), supine heel slide, terminal knee (short-arc) extension, clam, glute bridge, semi-stiff dead lift and posterior lunge. Eccentric quadriceps strengthening is more effective than concentric exercise in the treatment of PFPS. (36)

Manipulation may be necessary for restrictions in the lumbosacral and lower extremity joints. Hypermobility is common in the ipsilateral SI joint, with restrictions present contralaterally. Patellofemoral problems are part of a complex biomechanical chain, and corrective taping, including “McConnell taping” is generally ineffective. (37,38) Kinesiotape for PFPS has anecdotal support. Glucosamine sulfate may provide benefit.

Arch supports or custom orthotics may be necessary to correct hyperpronation. Research has shown that runners with anterior knee pain benefit from a combination of exercise and foot orthotics. (39) Runners should change shoes every 250 to 500 miles. Mesenchymal stem cells have demonstrated utility for managing isolated osteochondral defects in the knee. (44) A surgical “lateral release” of the lateral retinaculum is a last resort when conservative measures have failed.

References

1. Powers CM. The influence of altered lower-extremity kinematics on patellofemoral joint dysfunction: a theoretical perspective. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2003 Nov;33(11):639-46. Link

2. Thomeé R, Augustsson J, Karlsson J. Patellofemoral pain syndrome. Sports medicine. 1999 Oct 1;28(4):245-62. Link

3. Sartoris DJ, Resnick D. Diagnosis of bone and joint disorders.

4. Kannus P, Natri A, Paakkala T, Järvinen M. An outcome study of chronic patellofemoral pain syndrome. Seven-year follow-up of patients in a randomized, controlled trial. JBJS. 1999 Mar 1;81(3):355-63. Link

5. Duke Orthopaedic’s. Wheeles Textbook of Orthopedics. Chondromalacia of the Patella. Link

6. Froimson MI, Ratcliffe A, Gardner TR, Mow VC. Differences in patellofemoral joint cartilage material properties and their significance to the etiology of cartilage surface fibrillation. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 1997 Nov 1;5(6):377-86. Link

7. Puniello MS. Iliotibial band tightness and medial patellar glide in patients with patellofemoral dysfunction. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 1993 Mar;17(3):144-8. Link

8. Waryasz GR, McDermott AY. Patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS): A systematic review of anatomy and potential risk factors. Dynamic medicine. 2008 Dec;7(1):9. Link

9. Lankhorst NE, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, Middelkoop MV. Risk Factors for Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome: A Systematic Review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. Epub 25 October 2011. Doi: 10.2519/jospt 2012.3803.

10. Piva SR, Fitzgerald GK, Wisniewski S, Delitto A. Predictors of pain and function outcome after rehabilitation in patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome. Journal of rehabilitation medicine. 2009 Jul 5;41(8):604-12. Link

11. Boling MC, Padua DA, Marshall SW, Guskiewicz K, Pyne S, Beutler A. A prospective investigation of biomechanical risk factors for patellofemoral pain syndrome: the Joint Undertaking to Monitor and Prevent ACL Injury (JUMP-ACL) cohort. The American journal of sports medicine. 2009 Nov;37(11):2108-16. Link

12. Ireland ML, Willson JD, Ballantyne BT, Davis IM. Hip strength in females with and without patellofemoral pain. Journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2003 Nov;33(11):671-6. Link

13. Bolgla LA, Malone TR, Umberger BR, Uhl TL. Hip strength and hip and knee kinematics during stair descent in females with and without patellofemoral pain syndrome. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2008 Jan;38(1):12-8. Link

14. Al-Rawi Z, Nessan AH. Joint hypermobility in patients with chondromalacia patellae. British journal of rheumatology. 1997 Dec 1;36(12):1324-7. Link

15. Stoller DW, editor. Magnetic resonance imaging in orthopaedics and sports medicine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. Link

16. Järvelä T, Paakkala T, Kannus P, Järvinen M. The incidence of patellofemoral osteoarthritis and associated findings 7 years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with a bone-patellar tendon-bone autograft. The American journal of sports medicine. 2001 Jan;29(1):18-24. Link

18. Thomeé R, Augustsson J, Karlsson J. Patellofemoral pain syndrome. Sports medicine. 1999 Oct 1;28(4):245-62. Link

19. Zappala FG, Taffel CB, Scuderi GR. Rehabilitation of patellofemoral joint disorders. The Orthopedic Clinics of North America. 1992 Oct;23(4):555-66. Link

20. Liebenson C. Functional problems associated with the knee—Part one: Sources of biomechancial overload. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 2006 Oct 1;10(4):306-11. Link

21. Abernethy P, Wilson G, Logan P. Strength and power assessment. Sports medicine. 1995 Jun 1;19(6):401-17. Link

22. Doberstein ST, Romeyn RL, Reineke DM. The diagnostic value of the Clarke sign in assessing chondromalacia patella. Journal of athletic training. 2008 Mar;43(2):190-6. Link

23. Cook C, Mabry L, Reiman MP, Hegedus EJ. Best tests/clinical findings for screening and diagnosis of patellofemoral pain syndrome: a systematic review. Physiotherapy. 2012 Jun 1;98(2):93-100. Link

24. Fitzgerald GK, McClure PW. Reliability of measurements obtained with four tests for patellofemoral alignment. Physical Therapy. 1995 Feb 1;75(2):84-90. Link

25. Watson CJ, Propps M, Galt W, Redding A, Dobbs D. Reliability of McConnell’s classification of patellar orientation in symptomatic and asymptomatic subjects. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. 1999 Jul;29(7):378-85. Link

26. Huberti HH, Hayes WC. Patellofemoral contact pressures. The influence of q-angle and tendofemoral contact. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1984 Jun;66(5):715-24. Link

27. Tomsich DA, Nitz AJ, Threlkeld AJ, Shapiro R. Patellofemoral alignment: reliability. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 1996 Mar;23(3):200-8. Link

28. Reid DC. Sports injury assessment and rehabilitation. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1992:345–98.

29. Dixit S, Difiori JP, Burton M, Mines B. Management of patellofemoral pain syndrome. Am Fam Physician. 2007 Jan 15;75(2):194-202. Link

30. McCauley TR, Kornaat PR, Jee WH. Central osteophytes in the knee: prevalence and association with cartilage defects on MR imaging. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2001 Feb;176(2):359-64. Link

31. Gold GE, McCauley TR, Gray ML, Disler DG. Special Focus Session: What’s New in Cartilage?. Radiographics. 2003 Sep;23(5):1227-42. Link

32. Pihlajamäki HK, Kuikka PI, Leppänen VV, Kiuru MJ, Mattila VM. Reliability of clinical findings and magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of chondromalacia patellae. JBJS. 2010 Apr 1;92(4):927-34. Link

33. Calmbach WL, Hutchens M. Evaluation of patients presenting with knee pain: Part II. Differential diagnosis. American family physician. 2003 Sep;68(5):917-22. Link

34. Powers CM. The influence of altered lower-extremity kinematics on patellofemoral joint dysfunction: a theoretical perspective. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2003 Nov;33(11):639-46. Link

36. Hafez AR, Zakaria A, Buragadda S. Eccentric versus concentric contraction of quadriceps muscles in treatment of chondromalacia patellae. World J Med Sci. 2012;7(3):197-203. Link

37. Warden SJ, Hinman RS, Watson Jr MA, Avin KG, Bialocerkowski AE, Crossley KM. Patellar taping and bracing for the treatment of chronic knee pain: A systematic review and meta?analysis. Arthritis Care & Research: Official Journal of the American College of Rheumatology. 2008 Jan;59(1):73-83. Link

38. McConnell J. The management of chondromalacia patellae: a long term solution. The Australian Journal of Physiotherapy. 1986;32(4):215-23. Link

39. Eng JJ, Pierrynowski MR. Evaluation of soft foot orthotics in the treatment of patellofemoral pain syndrome. Physical therapy. 1993 Feb 1;73(2):62-8. Link

40. Rathleff MS, Rathleff CR, Crossley KM, Barton CJ. Is hip strength a risk factor for patellofemoral pain? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2014 Jul 1;48(14):1088-. Link

41. Rozenfeld E, Finestone AS, Moran U, Damri E, Kalichman L. The prevalence of myofascial trigger points in hip and thigh areas in anterior knee pain patients. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 2019 May 14. Link

42. Samani M, Ghaffarinejad F, Abolahrari-Shirazi S, Khodadadi T, Roshan F. Prevalence and sensitivity of trigger points in lumbo-pelvic-hip muscles in patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 2019 Oct 15. Link

43. Ahmad Z, Murakami AM, Engebretsen L, Jarraya M, Roemer FW, Guermazi A, Kompel AJ. Knee cartilage damage and concomitant internal derangement on MRI in athletes competing at the Rio de Janeiro 2016 Summer Olympics. European Journal of Radiology Open. 2020 Jan 1;7:100258. Link

44. Jaibaji M, Jaibaji R, Volpin A. Mesenchymal Stem Cells in the Treatment of Cartilage Defects of the Knee: A Systematic Review of the Clinical Outcomes. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2021 Feb 8:0363546520986812. Link

Clinical Pearls

* The spectrum of PFPS begins with asymptomatic functional malalignment of the patella and ends in severe patellofemoral arthritis. The diagnosis of “Chondromalacia patellae” (CMP) occupies the mid-portion of the PFPS continuum- beginning with visible cartilage alterations and eventually leading to patellofemoral arthritis.

*Weakness in the quadriceps or hamstring muscles increases one’s risk of developing patellofemoral pain three to five fold.

* Differentiation of meniscal pain from patellofemoral pain may be accomplished by having the patient perform a two-legged squat- meniscal pain is generated at the bottom of the squat, while patellofemoral pain is present during descent and ascent.